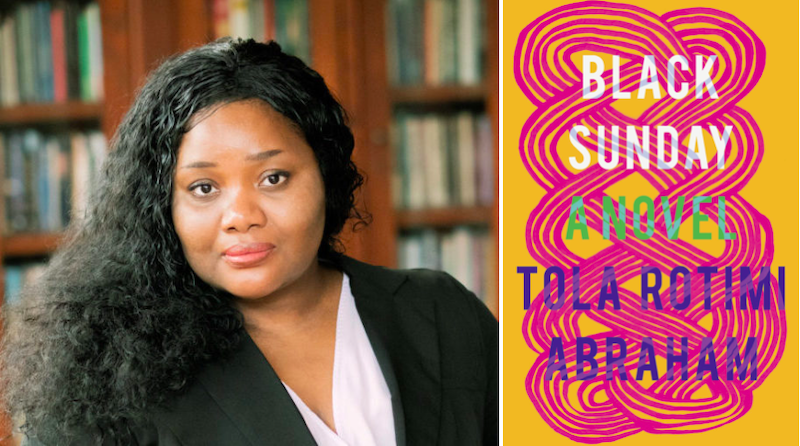

Tola Rotimi Abraham’s novel Black Sunday is published today. She shares five brilliant African novels with strong female characters.

We Need New Names by NoViolet Bulawayo

Darling, the main character in this masterpiece by NoViolet, is absolutely unforgettable. Even though when the book begins she is a child living in a slum in Zimbabwe, the voice with which she renders this story is brilliant, riveting, funny and sad.

Jane Ciabattari: Darling is sharp-eyed, witty, exuberant, and spot-on when it comes to describing the dangers of postwar Zimbabwe and the failures of the American dream. The language is extraordinary. Her description of a photograph of her late grandfather, for instance:

“He was killed before I was born, but I knew who he was the moment I laid my eyes on him for the first time; it felt as if I were looking at myself and Makhosi and my Father and my uncle Muzi and my other relatives, like my grandfather’s face was a folded fist and all our faces were collected like coins inside it.”

Or lines like “I know London. I ate some sweets from there once. They were sweet at first, and then they just changed to sour in my mouth.” Or her description of bull guavas, which “stay green on the outside, pink and fluffy on the inside, and taste so good I cannot even explain it.” Do you have favorite sections?

Tola Rotimi Abraham: One thing NoViolet does peerlessly well is the sharpness of Darling’s language. She gives us vivid, accurate, and unflinching descriptions of her life, despite the child’s limited perspective. I have many favorites, but I’m particularly impressed by the language in the later chapters. Darling moves to America, gets better at English, she has more words, but she’s exponentially less interesting. I am convinced that this was a deliberate choice. NoViolet Bulawayo is such a skilled writer, she renders what immigration sometimes does to the African imagination so stealthily.

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Chimamanda’s Ifemelu is a brilliant African woman with a beautiful love story. My favorite thing is that the love story does not take center stage in this novel; Ifemelu’s personal political evolution does.

JC: From her first novel, Chimamanda has impressed me as a transnational literary phenomenon. Americanah, which won the National Book Critics Circle fiction award (Half of a Yellow Sun was an NBCC fiction finalist) is a socially acute snapshot of a chaotic moment in time in which she nails the idiosyncracies of three cultures—Nigeria, the U.S., the U.K. She’s not just wicked smart, but wicked funny. She ranges from gently mocking to devastating in her call-outs. How much do you think Chimamanda uses humor to shape our sense of Ifemelu’s evolution?

TRA: I agree! Americanah has so many absolutely hilarious moments. It uses a very Nigerian humor. It’s caustic, observatory, it’s a self-aware kind, not afraid to laugh at oneself, you know?

There’s also a bit of exaggerating for comedic effect; perhaps for this reason the humor in Americanah was lost on a lot of readers. Because it’s so dependent on a shared lived experience. I think this quote is so funny, especially “your mouth will hang open in confusion”:

“If you’re telling a non-black person about something racist that happened to you, make sure you …This applies only for white liberals, by the way. Don’t even bother telling a white conservative about anything racist that happened to you. Because the conservative will tell you that YOU are the real racist and your mouth will hang open in confusion.”

So Long a Letter by Mariama Bâ

First published in the 1980’s, the Senegalese author’s epistolary novel is one the first African feminist texts I ever read. Ramatoulaye writes to Assiatou, her childhood friend, with news of her husband passing. Later, we learn of the husband’s betrayal by marrying his oldest daughter’s classmate. The language is successful in balancing its overarching melancholy with fast paced, descriptive language.

JC: By shaping her novel in the form of a letter to a longtime friend, Bâ creates an intimate tone—“The presence of my co-wife beside me irritates me…” and “This is the moment dreaded by every Senegalese woman, the moment she sacrifices her possessions as gifts to her family-in-law…” Do you think this frankness helps carry the novel?

TRA: The epistolary form definitely contributes to So Long a Letter’s verisimilitude, which is such a pleasant surprise. Ordinarily you are taught the primacy of setting, scene, and linear progression, right?

But with this letter from friend to friend, with this exchange between co-passengers in bereavement, we do not even have to think of the reliability of this narrator or the sequence of narrated events. All we know is that this letter is something Ramatoulaye needed to write. This is why the form works—she has us sitting in there with her, in the thick of this murky mix of anger and sadness.

Everything Good Will Come by Sefi Atta

Sefi Atta’s Sheri is an unlikely feminist hero. Although the book’s character narrator is Enitan, Sheri, a neighbor who befriends Enitan as a child, is my favorite character. She is witty, tenacious, and a survivor who eventually takes advantage of the patriarchy to achieve her own agency.

JC: One could say that Enitan is more likely to follow the rules, at least at first (she does rebel against her marriage in the end), and Sheri more likely to break them. What are the factors that made Sheri so independent?

TRA: The first factor I can think of is that Sheri is obviously different: she’s mixed-race, she’s an outsider. She’s also been abandoned by her white birth mother and is being raised by her Yoruba grandmother, so even though she has these apparent physical connections to whiteness, she has no cultural connections.

“Outsider” therefore is an identity thrust upon Sheri. She had only two choices; accept it or fight it. By the end of the book, Sheri’s personality is big and unforgettable, she’s become rather purposeful with her life; the persona she eventually develops is deeply rooted in Lagos and Yoruba culture.

Behold the Dreamers by Imbolo Mbue

There’s something about Neni. She is the wife of Jende, the book’s main character. They are a Cameroonian family living in New York hoping to get legal papers. Neni is hardworking, level-headed and resourceful. She takes the many disappointments of immigrant life in stride. She’s inspiring.

JC: Neni has moments of being crushed—worried that “she had traveled to America only to be reminded of how powerless she was, how unfair life could be.” How does Mbue show us her ability to rise above her fears?

TRA: Neni is very honest about her struggles; she’s one of those immigrants torn between longing for America and what it represents, even though she’s living there and longing for Cameroon—even though she’s trying to convince the US government that it’s too dangerous for the family to go back there.

She’s very matter-of-fact in conversation, riding above all of that inner conflict by just living a regular life: being a wife, mom, employee, and friend.

In literature we often talk about the immigrant’s self-invention, and I think that it can be such a middle-class concern. It was so refreshing to read a character who wasn’t giving us paragraphs of interiority as she grappled with her immigrant identity; she just lived her life.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·