Vanessa Hua’s Deceit and Other Possibilities is published this month. She shares five books that tell the immigrant story.

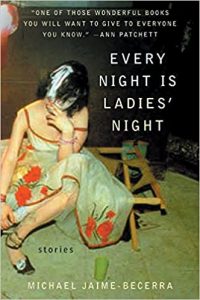

Every Night is Ladies Night by Michael Jaime-Becerra

A collection of linked short stories about Mexican immigrants and the children of immigrants in El Monte, a working class city in San Gabriel Valley, east of downtown Los Angeles. With spot-on setting and dialogue, his characters are vivid and compelling—shining a light onto stories outside of the dominant narrative.

Jane Ciabattari: Hector Cruz and his nephew Lencho weave a thread through this collection. I especially enjoy the deus ex machina role Lencho plays in “Media Vuelta,” the story of an older generation mariachi guitarist whose search for Rubi, his first wife (and first love) takes him from Chihuahua to El Monte. Do you have a favorite among these stories?

Vanessa Hua: “Media Vuelta” is a favorite of mine, too, and I marvel at the time and distance Jaime-Becerra so succinctly and lyrically depicts. It’s impossible for me to choose just one story, though; I loved the collection as a whole, and how it illuminates these lives and this landscape with a precision born out of a deep love and familiarity.

The Buddha in the Attic by Julie Otsuka

A lyrical novel told in the first person plural about Japanese picture brides, the novel is mesmerizing, by turns intimate and sweeping.

JC: With her first line, “On the boat we were mostly virgins,” Otsuka plunges us into the collective awareness of these picture brides. “We had long black hair and flat wide feet and we were not very tall. Some of us had eaten nothing but rice gruel as young girls and had slightly bowed legs, and some of us were only fourteen years old and were still young girls ourselves.” How do you think her use of the first-person plural point of view helps her conjure up the lost voices of a generation of Japanese American women without losing sight of the distinct experience of each?

VH: So often, outsiders may view another community as a monolith—one voice, one mind, one narrative. The danger of a single story is that it flattens people into stereotype. Otsuka brilliantly portrays their shared history with the first person plural, which acts as a chorus chanting this communal history, while allowing for moments when a soloist can step forward.

The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story by Edwidge Danticat

Part-craft guide, part-memoir, Danticat poignantly and powerfully writes about her mother’s death and the earthquake in Haiti, as well as examining deaths in Sula, Ghana Must Go, The Lovely Bones, and other fictions that contemplate this final mystery of human existence.

JC: As you note, The Art of Death is an original and incisive work of criticism, tracing how other writers—Tolstoy, Camus, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Toni Morrison, Joan Didion, Susan Sontag, and others—have written about the fact of death. At one point Danticat compares the stories in Haruki Murakami’s After the Quake to her own experiences of shock and loss in the merciless 2010 earthquake in Haiti. “Murakami’s characters display a whole range of reactions,” she writes, “from numbness to flights of magical realism that some might consider madness or simply grief. The earthquake, though, is not the central focus of these stories; the aftershocks are.” It’s part of Graywolf’s “craft” series, but The Art of Death is also an eloquent elegy for Danticat’s mother, who died of cancer, and a meditation on their relationship as etched in memory and in deathbed conversations. How do you think the personal revelations amplify her teaching of craft?

VH: Danticat’s personal revelations lend an urgency to the craft lessons, a reminder of how art can help writers and readers alike navigate through grief and how to honor death by writing with a clear-eyed gaze.

America is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo

The main character, Hero de Vera, flees political turmoil in the Philippines to make a new life in the San Francisco Bay Area. A queer love story of family that’s witty and poignant.

JC: I love the language. In her opening, for instance, Castillo writes, “When you’re old enough to know better but not old enough to actually stop talking back to him, your father will remind you, usually by throwing a chair at your head, that the only reason you’re able to attend nursing school is thanks to his army dollars. It’s your first introduction to debt, to utang na loob, the long drawn-out torch song of filial loyalty. But when it comes to genres, you prefer a heist: take the money and run.” What’s the secret of Castillo’s voice?

VH: The prose is exquisite and vivid—at times lyrical and magical, at times earthy and hilarious. That contrast is a strength of Castillo’s, and kept me enchanted throughout.

Severance by Ling Ma

A dystopian novel about late stage capitalism, zombies, and immigration. It’s eerie, darkly funny, and deeply moving.

JC: Does the structure of Severance, alternating between a “present” in the fall of 2011 and flashbacks giving us the past of narrator Candace Chen, a Brooklynite whose parents immigrated from Fuzhou to Utah, add to the emotional impact?

VH: The world is ending with a zombie pandemic, and yet Candace has already lived through another kind of apocalypse—the loss of her parents, the loss of language and culture. This context adds much poignancy, especially when she discovers that she’s pregnant. What will be her fate and the baby’s—and the generations past they each carry within?

*

· Previous entries in this series ·