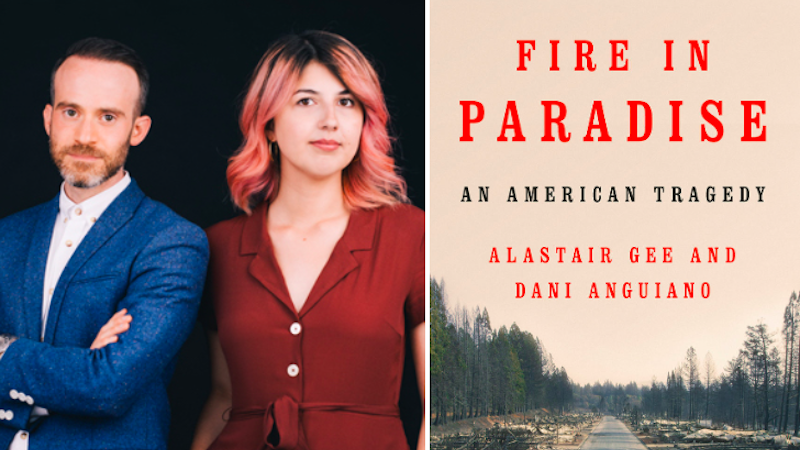

Alastair Gee and Dani Anguiano’s Fire in Paradise was just published. The two of them share five books that offer a master class in reported nonfiction.

Young Men and Fire by Norman Maclean

Alastair Gee: When he published it in the early 1990s, Maclean’s book was about an event already some forty years past: the terrible Mann Gulch fire, which killed thirteen Montana firefighters in 1949. It is the product of—I don’t use this word lightly—obsessive research and it grabs you by the throat, both conjuring and mythicizing the men who died. Interwoven with the narrative are Maclean’s musings on why it’s worth telling the story of such a disaster in the first place. He writes of how awful it would be if we just surrendered these men to history, “smoke drifting away and leaving terror without consolation of explanation.”

Dani Anguiano: Every word of Young Men and Fire feels like it was carefully written over the course of years—because it was. Maclean’s devotion to these men and their story can’t help but inspire similar feelings in the reader. After almost three decades, it stands as an essential piece of reported nonfiction.

Jane Ciabattari: For both of you: Did you think of Fire in Paradise as, in part, a memorial to those lost? And has your own impetus to write of the Paradise Fire included similar feelings?

Alastair Gee: To me writing often feels like an act of preservation, of saving stories and lives from the abyss. We wanted to memorialize not only the eighty-five lives that were lost but also the more ineffable aspects of life in Paradise—the glorious outdoors, the intimacies of small-town life.

Dani Anguiano: We wrote Fire in Paradise intending to tell not only the story of the Camp Fire, the deadliest US wildfire in a century, but of California’s Paradise Ridge and the resilient, brave people who called it home. My hope is that our book will help ensure we don’t forget those who perished in the flames, and that is what I kept in mind over the year we spent surveying the ruins of the fire, speaking with bereaved survivors and documenting the area’s recovery.

Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City by Matthew Desmond

Dani: Evicted demonstrates the incomparable value of immersive reporting. A sociologist by training, Desmond chronicles the lives of Milwaukee’s most vulnerable through the devastating and all too common occurrence of eviction with the thoroughness and care that comes from having witnessed it firsthand.

Alastair: Desmond doesn’t just drop into these people’s lives; he literally moves into the trailer park alongside them so he can better understand their plight. I read this book soon after being appointed the Guardian’s homelessness editor in 2017. I remember poring over it while on a trip to Salt Lake City, where I was visiting a hospice for homeless people, and texting my boss: This is the kind of reporting I want to do.

JC: Dani, you make a good point, that being a firsthand witness makes a narrative like Desmond’s work. How much do you think his training as a sociologist contributed to the book?

DA: I imagine Desmond’s training in the social sciences contributed a great deal—Evicted is ethnography. What makes the book so compelling is that it goes beyond just data, and illustrates systemic problems with individual stories.

JC: Alastair, have you also found yourself living among the homeless for your reporting? How has that affected your work?

AG: I never lived on the streets, but I made it my mission to spend as much time with people who did, wandering through cities like Los Angeles or Oakland and simply saying hello. Once a homeless man who lived in an RV with his family in an industrial part of San Francisco told me how the body of his friend had been found in a nearby dumpster. Six months of reporting later, this became the story “Death in an Amazon Dumpster.”

Five Days at Memorial: Life and Death in a Storm-Ravaged Hospital by Sheri Fink

Alastair: Fink notes at the beginning of this book that she was not at the hospital to witness the horrifying events she describes—doctors euthanizing seriously ill patients trapped in a flooded New Orleans hospital after Hurricane Katrina. But from the first sentence, as the throbbing of the helicopter blades pulses through the building’s shattered windows, we live the experience of the survivors along with them.

Dani: Sheri Fink vividly sets the scene—the struggles of staff and patients in an unprecedented disaster—and the circumstances that led to unthinkable decisions at Memorial Medical Center during Hurricane Katrina. Not only is it the most deeply reported account available of this tragedy, it also serves as a solemn and chilling warning.

JC: Alastair, how did that point of view—of survivors, not of witnesses of the events—create narrative drama?

AG: Fink accomplishes one of the hallmarks (for me) of the best narrative nonfiction. Through the stories of these survivors, she takes us inside a sequence of events that is, on the outside, utterly incomprehensible, and helps us to understand how the impossible became possible.

JC: Dani, Fink’s perspective allows us to understand all the points of view involved. Was any particular point of view less believable? Or did they all work equally for you?

DA: Fink has a gift for capturing the complexity of people and what drives them. The various points of view worked in the sense that I finished the book feeling like I understood the motivations of each person in the choices they made, regardless of whether those were the right choices.

She Said: Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story That Helped Ignite a Movement by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey

Dani: Written by the reporters who first broke the Harvey Weinstein story, this book shows journalism at its best—holding the powerful to account and giving a voice to those who have been silenced. It also provides an inside look at the reporting techniques of two of the best reporters in the country, and how they convinced people to open up about some of the most painful moments in their lives.

Alastair: This is the reporting that helped give rise to one of the most important social reckonings of the century so far—the #metoo movement. And how many works of Pulitzer Prize-worthy journalism end with a gathering of women including Christine Blasey Ford and Ashley Judd at the home of none other than Gwyneth Paltrow?

JC: Dani, what were the most effective ways these reporters helped people share their stories?

DA: They straightforwardly told prospective sources why they were trying to report the story, and explained their track record with similar reporting. They were mindful of the survivors’ trauma and recognized the struggles they faced, which is essential when asking people to be vulnerable and open about their lives. I tried to take that thoughtful, measured approach while interviewing people for Fire in Paradise, and my background as a local journalist with ties to the area (some of my family were affected by the fire) helped build trust with sources.

JC: Alastair, to what extent do you think the celebrity of Weinstein and those who testified against him made this narrative work? Would this book have drawn this much attention without that celebrity factor?

AG: With or without the celebrity factor, Weinstein was an unbelievably prolific abuser, but of course (and regrettably) his fame contributed to the urgency of the story. Reporters had been digging for information and trying to get his accusers on the record for years.

Midnight in Chernobyl: The Untold Story of the World’s Greatest Nuclear Disaster by Adam Higginbotham

Dani: Adam Higginbotham’s portrait of what happened at Chernobyl is akin to time travel. He vividly reconstructs the disaster and everything that led to it with such skill that the reader can almost smell the freshly mowed grass in the town of Pripyat, where the plant was located. It’s a testament to the power of careful, painstaking reporting.

Alastair: The horrors of the Soviet Union exert a particular pull on me, in part because I lived and reported in Moscow for four years. A.A. Gill’s story on the destruction of the Aral Sea is probably what inspired me to become a journalist in the first place, and C.J. Chivers’ feature on the Beslan school bombing is unforgettable. But for its depth and precision and urgency, Higginbotham’s book is in a league of its own. How did he do this, I find myself marveling.

JC: Dani, how much of a challenge do you think the element of secrecy in the former Soviet Union at the time of the Chernobyl meltdown, and the limited amount of information declassified archives, was to the author?

DA: Reportage as in-depth as Midnight in Chernobyl is challenging enough. Higginbotham’s work chronicling the untold story of Chernobyl decades later, given the intense secrecy that surrounded the disaster, makes the book an even more impressive feat.

JC: Alastair, having worked on Moscow Times, I’ll ask you the same question. How much has changed in terms of secrecy and access to facts?

AG: I can only say from my own experience how different it is to report in Russia versus in the US. In Moscow, I sometimes felt as though I were barely tolerated. People put the phone down on me, opposition leaders warned me their phones were tapped or asked to meet me in safe houses, and I was even arrested. The exigencies of the current political moment aside, the freedom of the press in the US is a remarkable, a wonderful thing.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·