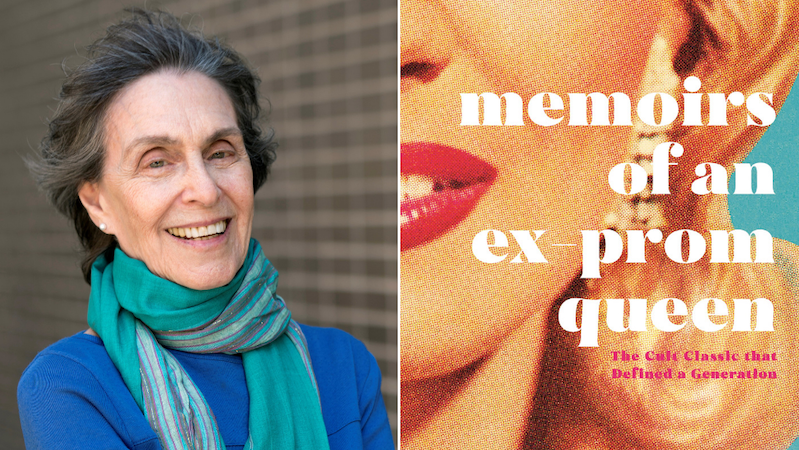

Alix Kates Shulman’s classic Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen is being reissued this month. She shares five books that made her a feminist.

Fifty years ago, notes Alix Kates Shulman, the prospects for women writers were very different than they are today. “The widespread sneer ‘lady writer,’ popular among the literati, kept many women from writing at all. The sudden emergence of a defiant women’s liberation movement in the late 1960s, and lessons I learned from literature, including from these five novels, helped me resist that sneer and write my books. By depicting sexual abuse and harassment in Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen I felt I was flouting the sneer.”

The Little Disturbances of Man by Grace Paley

In the early 1960s, Grace Paley was one of the few female American fiction writers widely admired by the male literary establishment for her style and wry wit. Her short stories about the daily lives of mothers included taking the kids to play in Washington Square Park—exactly how and where I spent my days! Paley’s stories demonstrated that what I knew best could be fit subject matter for fiction, despite frequent contemptuous reviews of “women’s fiction.” (I once collected such book reviews, including one headlined, “Another Novel with Prams in the Hall,” an echo of British literary eminence Cyril Connolly’s famous quote, “there is no more somber enemy of good art than the pram in the hall.”)

Jane Ciabattari: Can you remember how reading Paley’s work changed your writing? What’s the first of her stories you read? And the first of your stories you wrote after reading her?

Alix Kates Shulman: I believe I was not yet writing fiction when I discovered Paley. I was so bowled over by her stories of the domestic life of mothers raising children in the city in The Little Disturbances of Man that my very first attempt at a story was, unwittingly, a poor imitation of a Paley story. Even my title, “The Lost Girl Hunters,” was a knockoff of Paley’s “The Used-Boy Raisers.” My story was about the 1960s wave of young runaway girls, whose “missing” photos were pinned on trees all over Washington Square Park. Fortunately, I showed that story to no one. But years later, I returned to the subject, making a runaway girl one of three main characters (along with a pimp and a shopping bag lady) in my novel On the Stroll.

Native Son by Richard Wright

In an era when fiction with political intent was widely condemned, Wright’s haunting novel, with its clear political message, made me unafraid to write a political novel. It also showed me that presenting horrifying actions can serve a powerful literary purpose, and that “shocking” can be high praise.

JC: There’s that moment when Bigger Thomas awakens “suddenly and violently,” “like an electric switch being clicked on,” and he feels fear, “remembering he had killed Mary, had smothered her, had cut her head off and put her body in the fiery furnace.” This moment is shocking, yes, when it was first published in 1940, and ground breaking in its shift from gentility and denial to gritty reality of the aftermath of slavery. Are there particular passages that exemplify its political and literary intent?

AKS: The final section of the novel, encompassing Bigger’s murder trial, is an impassioned social-political-historical explanation of Bigger’s life, as presented by Boris Max, Bigger’s sympathetic communist lawyer. In his defense of Bigger, particularly in his closing statement, Max explains Bigger’s life and all that has come before in the novel—from his social circumstances to the details of his crimes—in terms of the racist legacy of slavery. Although some critics consider this final, explanatory section to be the novel’s weakest, in it, Wright lays out his literary and political intent. In Prom Queen, I deliberately avoided explaining my intent—but then my novel’s heroine is a recipient, not a perpetrator, of shocking violence.

To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

How begin to describe the permission Woolf’s feminism and artistry bestowed on the hopeful beginner? For me, her work, which never panders, was a reliable antidote to literary men’s scorn or disregard. Her novels demonstrated that despised domesticity, including dinner parties and shopping, could be transformed into unrivaled art. In To the Lighthouse she pokes fun at everyday male presumption and bombast, and the painter character, Lily Briscoe, embodies a woman’s right to devote herself to her art.

JC: To the Lighthouse is a landmark that opened the door for so many of us on first reading. Lily Briscoe struggles with insecurities, doubts (Tansley’s dictum, “women can’t paint, women can’t write…” echoes in her mind), fear of criticism, before, at the end of the book, she takes upon herself the gaze, the point of view, no holds barred. How does her process through the stages mirror your own development as a writer?

AKS: In the absence of a women’s movement, doubt and insecurity like Lily Briscoe’s kept many women, including me, from daring to show—or even create—our art. (Historically, the exclusion and suppression of female visual artists was even greater than that of literary artists.) Only when a burgeoning women’s movement produced a feminist infrastructure of journals, publishers, bookstores, and eager audiences did many of us overcome “Tansley’s dictum” and develop the confidence we needed to write and publish. Woolf, the ardent feminist who imagined for us the unfortunate fate of Shakespeare’s sister and the eventual triumph of Lily Briscoe, created with her husband a publishing house, Hogarth Press, where they published her (and others’) work.

A Fan’s Notes by Frederick Exley

This 1968 sensation of a novel, now mostly forgotten, was so misogynistic that it fired my fury. Not that its misogyny was unusual; one might say that at the time misogynistic novels constituted an (unacknowledged) genre. Exley’s sexist novel incited me to sprinkle my own with sexist quotations by such revered authorities of the period as Dr. John Watson (Behaviorism) and Dr. Benjamin Spock (Baby and Child Care). One unexpected effect of A Fan’s Notes on my own novel was that I appropriated Exley’s central organizing conceit of a near-obsessive fixation: for his narrator it was with football great Frank Gifford; for my heroine it was physical beauty.

JC: The narrator of Exley’s “fictional memoir” idolizes his USC classmate, football great Frank Gifford, writing, “Frank Gifford went on to realize a fame in New York that only a visionary would have dared hoped for: he became unavoidable, part of the city’s hard mentality. I would never envy or begrudge him that fame. I did, in fact, become perhaps his most enthusiastic fan. No doubt he came to represent to me the realization of life’s large promises.” Did you choose that narrative perspective intentionally? Or did it emerge as you worked on Prom Queen? And how might you encourage women today to use the energy of fury to fire their work?

AKS: I got the idea to write a novel about a prom queen fixated on her looks while marching at a protest of the 1968 Miss America beauty contest, that perfect symbol of the demeaning objectification of women. That same year, I read Exley’s sexist novel. The two influences merged before I began writing my novel. I think anger, or revenge, has always been one of the available motives for fiction, though it has been less acceptable for women writers. In today’s climate of renewed feminist activism and the angry energy of #MeToo, some women writers are already fired by fury. I think of such recent novels as Susan Choi’s Trust Exercise and Kate Walbert’s His Favorites, and such nonfiction works as Sara Ahmed’s Living a Feminist Life and Rebecca Traister’s Good and Mad.

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

I read Hurston’s forgotten 1937 masterpiece while I was switching my focus from the oppression I had depicted in my first novel, Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen, to the resistance I was dramatizing in my second, Burning Questions. Over the course of Hurston’s novel, the protagonist, Janie Crawford, develops from an abused and silenced wife into a strong-minded, independent, fearless heroine. Although Janie’s main search is for true love, to me her resistance to social presumptions and male control provided an inspiring model for the kind of rebel I hoped to create.

JC: While writing a novel tracking a woman’s shift from oppression to resistance, you encountered Hurston’s 1937 novel and it offered you a model. What a moment that must have been. Do you see moments now, since there are so many women being restored to visibility?

AKS: Such moments occur mainly when feminist movement is resurgent, as it is today. Amazingly, The New York Times now runs belated obituaries of women and people of color who, back when they lived and died, were ignored by the Times. Throughout the 1970s, feminist journals like Women: A Journal of Liberation (where, in 1970, I reintroduced the anarchist-feminist Emma Goldman, whose books were all out of print) and Ms. ran regular features on forgotten women who have since become mainstays of our culture. In a 1975 article in Ms., Alice Walker reintroduced Hurston to eager readers like me, who sought out second-hand copies of Her Eyes Were Watching God. After the novel was republished in 1978, it went on to became a bestseller, with 75,000 copies sold in a single month. Who knows who may be coming back next to enrich our lopsided literature?

*

· Previous entries in this series ·