Deirdre Bair’s Parisian Lives is published today. She shares five books that influenced her writing life.

Ulysses by James Joyce

It might seem strange for a biographer to choose a novel, but I have always seen much more than fiction in this one. To me, it is social and cultural history, literary criticism, and even biography. It is often said that if Dublin were destroyed, it could be recreated from Leopold Bloom’s peregrinations throughout the city. Joyce’s own life is there, too, not only in Poldy’s randy thoughts but in Molly’s soliloquy, which seems to be an extension of his and Nora’s private life. As for the Irish literary establishment, Joyce gets his digs in with his deadly accurate satires of the leading lights.

Jane Ciabattari: Can you offer some examples of those digs?

Deirdre Bair: Joyce takes on the Dublin literary establishment and much of Irish literature in the Scylla and Charybdis chapter (episode 9). If a new reader of Ulysses wants details, there’s an Annotated Ulysses that will give them all.

Samuel Beckett’s early fiction and plays

Having studied Ulysses so intensely, I turned naturally to Beckett. When I read More Pricks than Kicks, Murphy, and Watt, I recognized real places and real people within some of Beckett’s devastatingly accurate portrayals. After reading and seeing Waiting for Godot and Krapp’s Last Tape, I became convinced that he was not, as the critics then described him, “the poet of alienation, isolation, and despair.” Even though I had never really read biography and had no idea how to go about writing one, I was convinced that we needed a new direction in Beckett scholarship, and biography was the way to go. All I needed to do was to learn how to write one!

JC: Can you describe how that Beckett biography began? And how complicated it is when you’re writing about a living author who can work behind the scenes to influence the biography?

DB: The Beckett biography began when I was in graduate school and French literary theory ruled. I thought there was more to Beckett’s writing than that, and indeed there was, as I found out during the seven years it took to write his life. It’s far too complicated a story to go into detail here, but the first several chapters of Parisian Lives will give readers all the might want to know about how I came to write that book. It’s the same thing when I try to describe how I worked with Beckett: that, too, is a story too complex to summarize briefly. And as I do in all my biographies: I don’t take sides or tell the reader what to believe. When it comes to who influenced whom throughout the writing, this time I especially leave it to the reader to decide.

John Keats: The Making of a Poet by Aileen Ward

How fortunate I was to meet this impressive woman and to have her become my mentor and friend. Her biography of Keats exemplified the motto I adopted for my own work at the very beginning of my career, the literary critic Desmond McCarthy’s decree that the biographer must be “the artist under oath.” Constrained by the genre’s requirements of fact and truth, the writer still had to create a good story, a page turner that makes the reader eager to keep reading what she wrote. Ward’s biography was an inspiration.

JC: When did you first read Ward’s biography? Did you know at once how it might influence your own work?

DB: As soon as I knew I was going to be writing a biography, I started to read the genre seriously, and Ward’s book was among the first. I was struck immediately by the beauty of her prose and the way she structured the story of Keats’ life. I knew I wanted to write that way, too. When I met Aileen Ward and she invited me to participate in her biography seminar at NYU, I could not believe my good fortune to be among so many distinguished biographers, among them Carole Klein, Maynard Solomon, Kenneth Silverman, and Marion Meade. It was biography heaven.

Virginia Woolf’s Essays and Diaries

Whenever I am stumped—when I sit there asking myself where do I go with this topic, how do I portray this event, what truth can I find among all these conflicting versions of a life—I can open at random any volume of Woolf’s prose and find something inspirational and insightful that lets me move forward with my own writing.

JC: Woolf’s thinking seems so up to date, as she takes a position of authority in the midst of her most intimate and public writings. I love the way she gives her reading experience equal time. And I suspect many women have drawn inspiration from passages in the diary like this one:

…the habit of writing thus for my own eye only is good practice. It loosens the ligaments. Never mind the misses and the stumbles. Going at such a pace as I do I must make the most direct and instant shots at my object, and thus have to lay hands on words, choose them and shoot them with no more pause than is needed to put my pen in the ink. I believe that during the past year I can trace some increase of ease in my professional writing which I attribute to my casual half hours after tea. Moreover there looms ahead of me the shadow of some kind of form which a diary might attain to. I might in the course of time learn what it is that one can make of this loose, drifting material of life; finding another use for it than the use I put it to, so much more consciously and scrupulously, in fiction.

Do you have favorite passages, favorite essays you reread regularly?

DB: These days, I find myself turning the pages of Virginia Woolf’s writings randomly. Certainly, when I first read her essays, Granite and Rainbow and A Room of One’s Own resonated, but now, perhaps because writing Parisian Lives was so different from anything else I ever wrote, I roamed far and wide, counting on something to strike a chord in ways that I could compare to my own experiences and thus profit from her insights when I wrote my own.

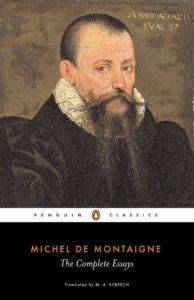

Montaigne’s Essays

This volume is always on my bedside table. Whenever the day’s news is too upsetting, or the writing did not go well, or some household crisis has me worrying about how to structure my next day, I can open this book to any one of his essays and find something that soothes my worried soul and sends me off to dreamland with a smile upon my face, knowing that I can always worry about tomorrow when the time comes.

JC: Do you have a preferred translation?

DB: I don’t have a preferred translation of Montaigne’s essays. I actually have copies throughout the house—in my office, in my so-called library, and next to my bed. Over the years I’ve picked up quite a few volumes, not to mention the French ones I buy in France, as almost every time I go to Paris, it seems there’s a new one.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·