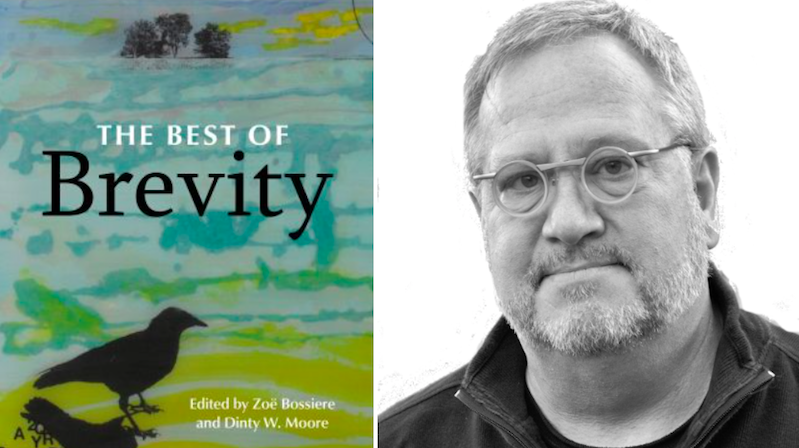

The Best of Brevity: Twenty Groundbreaking Years of Flash Nonfiction, edited by Zoe Bossiere and Dinty W. Moore, is published on November 17. Moore shares five books that have helped define flash nonfiction.

Maps to Anywhere by Bernard Cooper

The idea of the essay in brief form goes very far back—to Heraclitus, Seneca, and Sei Shōnagon, for instance—but the modern notion of what we now call flash nonfiction was kick-started in 1990 by Cooper’s elegant and unusual Maps to Anywhere.

Jane Ciabattari: Reviewers of Maps to Anywhere, Cooper’s first book, noted it was hard to categorize (Don Lee wrote, “To call it, simply, a collection of essays would be an injustice. For though it charts a number of disparate courses—philosophical, whimsical meditations on such subjects as baked potatoes, art, utopia, architecture, religion, and paleontology—a narrative arc develops, edges toward literary memoir.”) It grabbed attention, and also the PEN/Faulkner award. Why do you think Maps to Anywhere made this pioneering impact?

Dinty W. Moore: The impact, first and foremost, was due to Cooper’s graceful and sophisticated prose style, his utterly beautiful observational skills, and also, I think, because of the attributes the reviewer Don Lee mentions above. Maps to Anywhere was so wide-ranging, so spacious; Cooper showed us all what was possible, and in that way, he lit a fire under contemporary literary memoir (and the flash form as well).

In Short: A Collection of Brief Creative Nonfiction, edited by Judith Kitchen and Mary Paumier Jones

Editors Kitchen and Paumier Jones cite Bernard Cooper’s work as a major inspiration for this surprising anthology, but it was the anthology itself that began to define the genre and galvanize the flash nonfiction movement.

JC: Cooper was the kickstarter. Of the others, who do you think has had the most lasting impact?

DWM: The table of contents is a veritable roll call of literary nonfiction standouts (and quite a few poets too): Stuart Dybek, Judith Ortiz Cofer, Maxine Kumin, Terry Tempest Williams, Richard Rodriguez, Tobias Wolff, Rita Dove, Michael Ondaatje. Naomi Shihab Nye’s “Mint Snowball” is still widely taught, as is Henry Louis Gates’ “Sunday.” But honestly, I would need pages to list all of the outstanding essays and essayists in this collection. The editors did a stunning job. Vivian Gornick is in there. Lee Gutkind. Scott Russell Sanders. Diane Ackerman. Barry Lopez!

Leaping by Brian Doyle

Doyle was a force of nature, taken from us too soon. His brief essays, in this book and scattered throughout many of his others, read more like prayers or incantations, and can make you laugh or weep at unexpected moments.

JC: I can’t resist quoting Doyle’s “Leap” at length. I was in New York that day, and it may be the best evocation of the fall of the Twin Towers on September 11.

It begins,

A couple leaped from the south tower, hand in hand. They reached for each other and their hands met and they jumped.

Jennifer Brickhouse saw them falling, hand in hand.

Many people jumped. Perhaps hundreds. No one knows. They struck the pavement with such force that there was a pink mist in the air.

And later, Doyle writes,

I try to whisper prayers for the sudden dead and the harrowed families of the dead and the screaming souls of the murderers but I keep coming back to his hand and her hand nestled in each other with such extraordinary ordinary succinct ancient naked stunning perfect simple ferocious love.

Their hands reaching and joining are the most powerful prayer I can imagine, the most eloquent, the most graceful.

Amen.

Which essays make you laugh?

DWM: “Leap” is an amazing essay, and because of the subject at hand, there is no humor to be found. But setting that aside, Doyle found humor in just about everything, his love of basketball, his wrestling with God and faith, even his cancer. Little nuggets of wit are buried on nearly every page of his essay collections. I was privileged to publish a few of his flash essays in my magazine, Brevity. I still grin at “Ed” and laugh out loud at “Pop Art,” where he says of his three children: “They rise early in excitement and return reluctantly to barracks at night for fear of missing a shred of the daily circus. They eat nothing to speak of but grow at stunning rates that produce mostly leg. They are absorbed by dogs and toast. Mud and jelly accrue to them. They are at war with wasps. They eat no green things.”

Bluets by Maggie Nelson

Nelson shattered whatever barrier existed between prose poetry and flash nonfiction with her lyric takes on depression and the color blue, and this small volume has inspired countless essays and books since.

JC: Bluets came out in 2009; Nelson won the National Book Critics Circle Criticism award for The Argonauts, published in 2015. She has built her hybrid forms year by year. Whose work has drawn inspiration from hers over these years?

DWM: I am reluctant to say that certain works drew inspiration from Bluets without first reaching out to the authors and asking if my educated guesses are correct, but I suspect that memoirists such as Melissa Febos, Carmen Maria Machado, Roxane Gay, Leslie Jamison, and Lidia Yuknavitch might all agree that Bluets was a guiding light. And so many more works from authors whose names may be less well known. I can say without hesitation that my students who are entranced by the lyric essay are also in awe of Bluets, and The Argonauts, and all of Nelson’s work. I have taught these books and seen firsthand how they embolden younger writers. For instance, my former student Sarah Minor whose new collection is Bright Archive.

Heating & Cooling by Beth Ann Fennelly

This recent take on the flash nonfiction genre promises “52 micro-memoirs” in the subtitle, and delivers with precision, humor, and delight.

JC: Leave it to a poet laureate/novelist/memoirist to come up with a collection this surprising. The opening section, “Married Love,” one paragraph, goes like this:

In every book my husband’s written, a character named Colin suffers a horrible death. This is because my boyfriend before I met my husband was named Colin. In addition to being named Colin, he was Scottish, and an architect. So you understand my husband’s feelings of inadequacy. My husband cannot build a tall building of many stories. He can only build a story, and push Colin out of it.

Your turn.

DWM: And another, the full text of an exquisite flash entitled “I Come from a Long Line of Modest Achievers”:

I’m fond of recalling how my mother is fond of recalling how my great-grandfather was the very first person to walk across the Brooklyn Bridge on the second day.

Timing is everything.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·