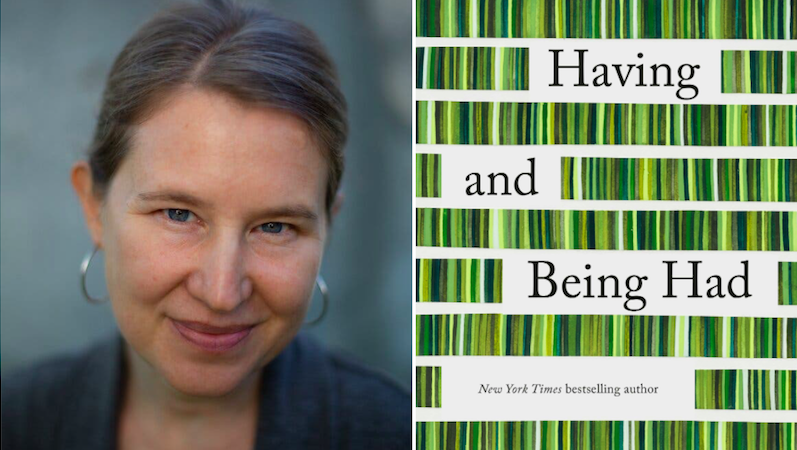

Eula Biss’s Having and Being Had has just been published. She shares five books that defy classification, noting, “These are all books that combine various modes—memoir, criticism, poetry, essay—in artful and inventive ways. And these are all books that helped me write Having and Being Had. They informed my approach to my subject matter more than my subject matter itself.”

The Women by Hilton Als

My undergraduate writing professor, Deb Gorlin, recommended that I read this book shortly after it was published in 1998, and I’ve been re-reading it ever since. I remember studying the description on the back of the book: “The Women is at once a memoir, a psychological study, a sociopolitical manifesto, and an incisive adventure in literary criticism.” I didn’t know what that meant, exactly, but I knew that the book felt aggressively alive, and that if what it did was all those things listed in the description, then all those things were what I wanted to do as a writer.

Jane Ciabattari: The opening paragraph in Chapter One alone encapsulates a life story:

Until the end, my mother never discussed her way of being. She avoided explaining the impetus behind her emigration from Barbados to Manhattan. She avoided explaining that she had not been motivated by the same desire for personal gain and opportunity that drove most female immigrants. She avoided recounting the fact that she had emigrated to America to follow the man who eventually became my father, and whom she had known in his previous incarnation as her first and only husband’s closest friend. She avoided explaining how she had left her husband—by whom she had two daughters—after he returned to Barbados from England and the Second World War addicted to morphine. She was silent about the fact that, having been married once, she refused to marry again. She avoided explaining that my father, who had grown up relatively rich in Barbados and whom she had known as a child, remained a child and emigrated to America with his mother and his two sisters—women whose home he never left. She never mentioned that she had been attracted to my father’s beauty and wealth partially because those were two things she would never know. She never discussed how she had visited my father in his room at night, and afterward crept down the stairs stealthily to return to her own home and her six children, four of them produced by her union with my father, who remained a child.…She avoided mentioning that she saw and understood where my fascination with certain aspects of her narrative—her emigration, her love, her kindness—would take me, a boy of seven, or eight, or ten: to the dark crawl space behind her closet, where I put on her hosiery one leg at a time, my heart racing, and, over those hose, my jeans and sneakers, so that I could have her—what I so admired and coveted—near me, always.

The spaciousness of this lengthy paragraph (much shortened above) is remarkable; how does the “negative”—she never, she avoided—accumulate to give us such a full picture of his mother?

Eula Biss: Yes, this is really masterful—he works silence and omission and avoidance into every sentence, so the picture seems full of holes even as it provides a sketch that might otherwise seem complete. The silence and the avoidance, he implies, is an essential part of the portrait, a central characteristic of his mother. And he also refuses to repeat that silence, with every line breaking the taboo of the unspoken.

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely by Claudia Rankine

This book was given to me by my editor at Graywolf, Jeff Shotts, when I first met him. I had the sense, when I was reading this book for the first time, that I was learning a new way of reading, a new logic on the page. Rankine bends both poetry and prose to her purposes, making metaphor out of information and information out of metaphor.

JC: “What alerts, alters,” Rankine writes. What rules does she break in that bending and shaping that suits our time?

EB: She’s unafraid to disorient the reader, which then allows her to re-orient the reader. (As a student of writing and then a teacher of writing, I’ve spent a lot of time in writing workshops, where “I’m confused by this” or “this is confusing” are among the most common critiques—the assumption being that there’s a rule against confusion. But what I’ve noticed in my own reading is that confusion and disorientation call me to attention and make me alert, ready to be altered.) In Don’t Let Me Be Lonely there’s a sickness, and it seems that sickness is in the narrator’s body, but the sickness is also in the nation, and after some disorientation, in my first read, it became clear that the sickness of the country was making the narrator sick, but to further complicate that metaphor, the drugs that are being used to treat the sickness are toxic.

Things that Are by Amy Leach

I met Amy in graduate school, and we have continued to trade drafts of our work over the fifteen years since we graduated. Her prose bears traces of romantic poetry and transcendentalist essay, but she sounds like nobody else on earth. She once described to me her process for revision and it was a process of distillation—she would reduce a paragraph down to a sentence, and then, if possible, reduce that sentence down to a word.

JC: Condensation! She also presents original images and concepts throughout. Like, “Sometimes it avails to be a goat. When the grass withers away in Morocco, sheep will stumble dully along, thinking horizontal thoughts. No grass … no grass. But goats look up, start climbing trees.” How has your ongoing trading with Amy Leach influenced your work?

EB: In many ways, but particularly in my appreciation of the virtues of compression. Amy’s process was very much on my mind as I wrote Having and Being Had. Many of the short titled works that compose this book could have been made much longer. Usually, I tend to write over-compressed drafts and my revision process involves expansion. But for this book my process of revision was often a process of condensation, even as I added material or ideas to a rough draft—I wanted to revise all the excess out of every moment I touched, so that every detail would be meaningful and, ideally, also metaphorical.

The Unquiet Grave by Cyril Connolly

This book was given to me on my fortieth birthday by the writer Sara Levine, who has a wonderful sense of humor in her life and her art. Connolly wrote this book the year he turned forty and it’s a strange document, a collection of quotes and aphorisms, memories and anxieties. It’s a midlife crisis that’s full of beautiful sentences, the kind of sentences that make me want to write a sentence.

JC: It’s a notebook, a compilation, causing pause at each turn: “Cowardice in living: without health and courage we cannot face the present or the germ of the future in the present, and we take refuge in evasion. Evasion through comfort, through society, through acquisitiveness, through the book-bed-bath defense system, above all through the past, the flight to the romantic womb of history,into primitive myth-making.” Do you have favorite passages?

EB: I love his list of evasions and find “the book-bed-bath defense system” particularly funny, ruefully funny. I also love his descriptions of the act of writing itself, where he conjures, with beautiful rhythms, a state of reverie: “O sacred solitary empty mornings, tranquil meditations—fruit of book-case and clock-tick, of note-book and arm-chair; golden and rewarding silence, influence of sun-dappled plan-trees, far-off noises of birds and horses, possession beyond price of a few cubic feet of air and some hours of leisure.”

Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit by Aisha Sabatini Sloan

This book was recommended to me by one of my graduate students, Min Li Chan. These essays draw their strategies from poetry and collage, and their subject matter from art and life and the streets of Detroit. Sloan is deft and inventive, endlessly smart and soulful in the way she approaches her cultural investigations.

JC: One compelling aspect of Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit is the fluidity with which she navigates time—juxtaposing the “now” (news of newly discovered Bin Laden documents reported on CNN at the Dallas airport, for instance, in the title essay) with the emotional memory of the past (“that weird swoon of time when I couldn’t stop watching Homeland because of the feeling of vertigo I got when the kind-eyed terrorist lost his son to a drone”) and with a glimpse the future: “Tonight, I will dream that I live in a city like the recently captured Ramadi. We have to make deals with the soldiers, who hold items on a pillow as we haggle for our lives.” How does her sense of time shape these essays?

EB: Yes, she moves through time so fluidly—that’s exactly the word for it! She’s a master time-bender. Her essay “D is for the Dance of the Hours,” which I particularly love, is set in contemporary Detroit but begins in her father’s childhood. Throughout that essay Detroit today is joined, by metaphor, to a centuries-old history of opera. The essay moves across one day in Detroit, but pulls that day toward the past in a way that stretches time and reminds the reader that the past, both near and far, is always present, always palpable in our day-to-day lives.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.