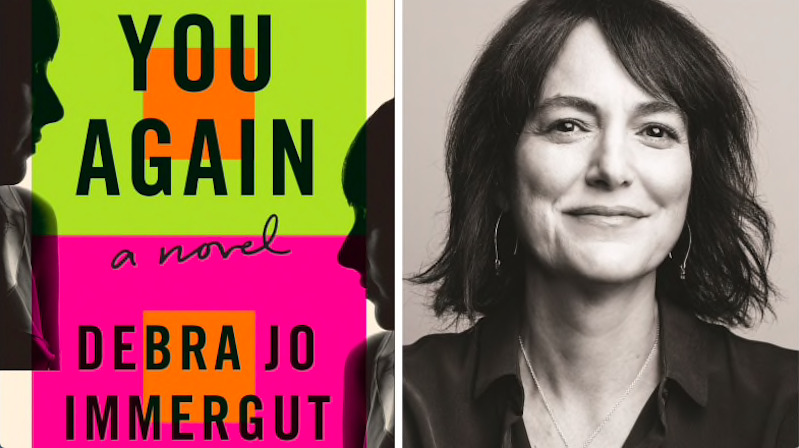

Debra Jo Immergut’s You Again has just been published. She offers five books that bend and fold time.

Life After Life by Kate Atkinson

Atkinson is one of my touchstones because, along with Ian McEwan, her work exemplifies a type of novel I love to read and aim to write—books that balance carefully wrought prose with swift plotting. In Life After Life, her heroine dies and is reborn repeatedly, revising outcomes as she goes. Atkinson’s narrative leaps and tumbles through loops of time, pulling the reader along for the ride.

Jane Ciabattari: Ursula Todd is born February 11, 1910. Over and over again she is born, her life unfolding in different ways through each lifetime. The “trick” is clear early on, yet the novel compels the reader to continue. How does Atkinson’s rhythm help her evoke the specifics of daily life so vividly that we follow Ursula through so many incarnations?

Debra Jo Immergut: For me, her voice has magnetic power. It’s so crisp and authoritative, but also warm and deeply human. When someone has that command of the language, we’re inclined to trust her and will follow her anywhere, I think. But with this book, it’s the daring of this narrative strategy—a life repeatedly restarting—and her brilliant execution of it. For example, we revisit the scene of Ursula’s birth countless times. Each time she describes it, Atkinson shifts perspective slightly, entering the mother’s point of view, or the maid’s, or the doctor’s, focusing her authorial attention on different objects in the bedroom, or different bits of dialogue. It’s a commentary on the myriad choices a novelist must make, as well as an exploration of the branching possibilities of a human timeline.

A Pale View of Hills by Kazuo Ishiguro

Ishiguro’s spare first novel slips seamlessly across decades to tell the stories of mothers and daughters in postwar Nagasaki and in exile in the West. While the dropping of the hydrogen bomb on Nagasaki is barely mentioned, the novel, in mysterious and heartbreaking fashion, explores what it might be like to live outside of time, in an eternal state of aftermath.

JC: What do you think anchors this post-nuclear narrative, with its shifts into the past and then the future? The mirroring of the two mothers, Netsuko and her two daughters, Niki and Keiko, who is a suicide after moving to England with her mother, and Sachiko, the mother of a disturbed daughter, Mariko?

DJI: It is a classic frame structure, a story within a story—but, actually, since you bring up the idea, I am now going to see it as a framed mirror. In recounting the fate of her friend Sachiko in long-ago Nagasaki, our first-person narrator, Netsuko, seems to be regarding her own pain over her daughter’s recent suicide—but she’s doing it at a remove, the way we see ourselves in a mirror. Ishiguro’s touch is so deft that we hardly detect an author’s hand at work. In fact, returning this one recently, I tried to vivisect it, which is an odd habit I have. I’ll reread with a notebook and pencil in hand, and I’ll note the time, setting, and characters in each scene. I think I’m trying to map its magic. I learn a lot about structure this way, but I also know that my favorite novels, like this one, have ineffable qualities that will never yield to diagramming.

A Pair of Blue Eyes by Thomas Hardy

He is probably my favorite novelist, and the famous cliff scene (famous among Hardy completists, anyhow!) is one of my favorites in all of literature. Amateur geologist Henry Knight dangles off the edge of a stone precipice, finds himself face to face with a fossilized prehistoric creature, and, as he contemplates the planet’s whole history, feels “time closed up before him like a fan.”

JC: And while he is dangling (in the cliffhanging prototype), his beloved Elfride dares all convention, and strips off her clothes to invent a rescue:

Behind the bank, whilst Knight reclined upon the dizzy slope waiting for death, she had taken off her whole clothing, and replaced only her outer bodice and skirt. Every thread of the remainder lay upon the ground in the form of a woolen and cotton rope.

Time stretches in Elfride’s case, as well, right?

DJI: Yes, though interestingly, while Henry Knight spends those moments of peril contemplating the origins of the universe and the fate of mankind, Elfride spends them thinking of Henry. His grateful embrace, after she cleverly and bravely rescues him with the rope made of her clothes, is described as “a glorious crown to all the years of her life.” Hardy tends to write strong, independent-minded female characters, but through the most male of gazes. What I love most about the scene is the way Hardy collapses time. Knight dangles on the cliff face and notices a trilobite fossil staring back at him. “Separated by millions of years in their lives, Knight and this underling seemed to have met at their death.” It reminds me of the notion, supported by Einstein’s theories and current quantum physics, that all of time is happening all at once—but we can only perceive it in a linear fashion. This is a key idea for my novel, and one I love to mull over.

Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward

In examining the toll of racial injustice on generations of lost boys, Ward awakens all the ghosts of Mississippi. With her interwoven narrative strands about restless souls, she also invokes the spirits of two other master time-twisters (and touchstones of mine), Faulkner and Morrison.

JC: One of Ward’s narrators, Jojo, thirteen, is a remarkable character, capable of watching carefully while his grandfather teaches him to butcher a goat, and of seeing the ghost of a boy imprisoned with his grandfather generations back at Parchman Farm, and also of seeing the scope of his heritage: “The branches are full. They are full with ghosts, two or three, all the way up to the top, to the feathered leaves.” He’s a time traveler of sorts. And his mother, Leonie?

DJI: Leonie occupies a purgatory between past and present, because of profound unresolved grief, and her sense of dislocation is worsened by drug use and a tortured though passionate relationship with Jojo’s father Michael. As she takes Jojo on a trip through Mississippi to retrieve Michael from prison, the ghost of her brother, who was murdered by white schoolmates, rides with them. The agony of his loss is still fresh, though he’s been dead for fifteen years. Through Leonie’s and Jojo’s hauntings, Ward also explores the idea that every moment is happening at once—all is unburied. She returns to this idea several times in the novel, echoing those quantum physicists. It’s fitting to quote Faulkner when you’re talking about Ward’s work—she has named him one of her favorite authors—so I’ll toss out his most overused line: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

M Train by Patti Smith

“Shard by shard, we are released from so-called time.” I almost used this line from M Train as the epigraph for You Again (I ended up with one from Borges instead), because I so admire the fluidity with which Smith follows her muse as it wanders through the years and moments of her life. In her mesmerizing, delicious books—I love all of them—she performs like an aikido master of memory.

JC: Patti Smith is indeed an “aikido master of memory!” She’s especially poignant in lines like this: “I’m going to remember everything, and then I’m going to write it all down. An aria to a coat. A requiem for a cafe.” What might you suggest she offers as a lesson for writers and readers during this pandemic time?

DJI: What a great question. I fervently hope Patti will write something about this period, because we’re going to need to remember everything. She has this aching, elegiac tone, and I think we’re going to need elegies after this period, with all the solitude and pausing and rethinking, then the cascading losses, and also this immense surge of opposition and protest and enough. So it’s like this great wave of history is washing over us, and once it has passed, we’re going to need to remember everything.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·