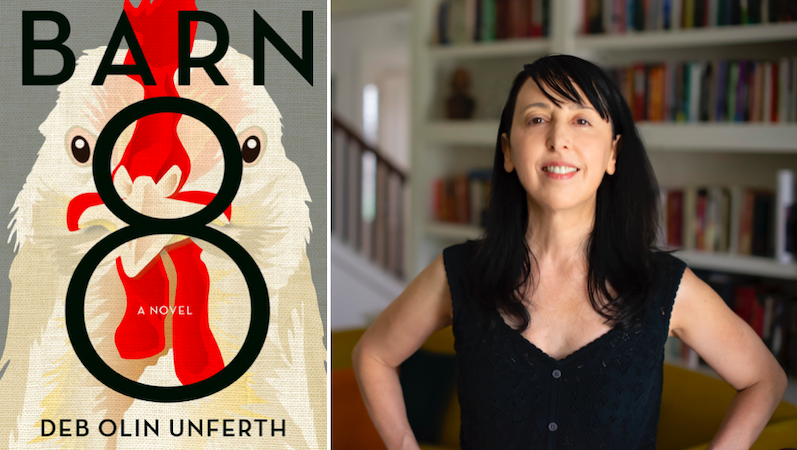

Deb Olin Unferth’s Barn 8 is published this month. She shares five books in her life, noting, “I’ve been teaching creative writing and literature at the Connally Unit maximum security prison in south Texas for nearly five years. The class runs its own small university library that grows a little each year. Here are a few favorite novels from the collection.”

The Sellout by Paul Beatty

I get complaints from the class that this book causes severe abdominal cramps. But this satire—a black man in Los Angeles reintroducing slavery and segregation—is beloved not only for its humor, but for its bravery and authenticity. It feels intimate to the students. Beatty could be talking to them: these are their jokes, these are their questions, these are their rages.

Jane Ciabattari: From the first line—”This may be hard to believe, coming from a black man, but I’ve never stolen anything”—Beatty’s tone is wry. That is part of the appeal, for sure, but also, as Beatty told Oscar Villalon in a 2018 interview after The Sellout won the National Book Critics Circle and Man Booker awards, “even some of the more ridiculous stuff in there, that you would think is obvious satire, is sort of real—or definitely based in something.” How much does the authenticity count?

Deb Olin Unferth: A lot! Isn’t that the role of the comedian—now and throughout history—to tell the truth? One difference between comedians has always seemed to me to be the quality of the laugh they get—bitter, whimsical, self-mocking, angry, wondering, light-hearted. To laugh at the truth is healing. When you laugh you have power.

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

When young Janie sees Joe Starks coming up the road speaking of “change and chance,” Hurston kicks off one of the greatest quests for independence and love of all time. Hurston’s playful poetic dialect—frowned on, back in 1937—slays the students. As one, Terrance Harvey, put it, “Hurston has a word-strainer that allows only the substance of rich life to meet the vellum.”

JC: Can you recall some of your students’ favorite passages?

DOU: They love Janie’s flirty ways and her spirited split decision-making. Mostly I think they fall in love with Janie’s voice, and with Hurston’s writing style by extension. They are bowled over by the idea that it’s okay to write this way. More than one student has told me it gives him permission.

Down the Rabbit Hole by Juan Pablo Villalobos

This is the story of a drug baron’s child. The kid wants a Pygmy hippopotamus! The voice in this novella is such an original mix of whimsy, weirdness, and innocence, set in front of a backdrop of extreme violence and drug-financed luxury. But it also contains grief my students understand: behind the curtain is the inadequate fumbling of a father trying to protect his child in this dangerous world.

JC: “I think at the moment my life is a little bit sordid. Or pathetic,” notes Tochtli, the ten-year-old narrator, with the wacky innocence that infuses this violent tale. Did the narrator’s age have an influence on this book’s popularity?

DOU: Perhaps. It’s sort of a twisted Santa fantasy, a drug lord willing to do anything to get his kid that perfect present. The playful child’s voice is funny and terrifying at once. But I think a lot of aspects of this novella hit home: the setting is Mexico, the narrative is suffused with mythology and words from Nahuatl, the largest indigenous language in Mexico. I think it’s meaningful. The unit has a large Latino population.

Less by Andrew Sean Greer

A romantic comedy about a gay, upper-middle-class, white, fifty-year-old man. Surprise! The students love it—maybe because the book is hilarious and beautiful. Or maybe they are just suckers for a good love story. Maybe it’s Greer’s confident writing. Or maybe to be out of the closet in a Texas prison isn’t quite so taboo as before.

JC: And perhaps it doesn’t hurt that this Pulitzer Prize winning novel takes its narrator on an around the world trip that includes Paris, Berlin, the Sahara, India and Japan?

DOU: I’m sure they liked reading about all those places. One delightful thing about the book though is that there is very little exoticizing of the locations. This is not Henry James. When the moment in the narrative calls for beauty—there is beauty. Voila! But when the moment calls for disappointment in that precise touristy way that makes you feel selfish and ungrateful, as well as disappointed—well, Greer is great at that.

When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka

What happened to a lonely Japanese family in the U.S. during World War II? This lyrical portrait, though serious, quiet, and small—the opposite of Beatty’s exuberant prose—speaks to the students’ souls: the father is imprisoned for years, the son loses all he ever knew, the homecoming is unfamiliar and hard.

JC: A Berkeley family suddenly dislocated, the father sent to prison for four years, the mother and two children sent to an internment camp in the Utah desert. Do you think Otsuka’s choice to use a different perspective for each of the five chapters—the mother, the daughter, the son, the homecoming, the father—helps make this first novel so powerful?

DOU: Yes, it is the voice that follows them and unites them. I’ve never read anything like this book. The craft and approach are so unique. It tells the story not only of this family but a whole community, one that the U.S. government decided to break into pieces and hide from sight, in the name of protecting the populace. I think the incarcerated students can relate to that.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·