David Biespiel’s memoir A Place of Exodus is published on September 30. He shares five books, one play and one film about the meaning of Texas.

The Path to Power: The Years of Lyndon Johnson by Robert A. Caro

If one meaning of Texas is political power, another is poverty. This is the first of the multi-volume biography Caro has been writing on President Lyndon Johnson for the last three decades. It tells the story of Johnson’s early years raised in one of the the state’s most desperately poor and isolated areas, the Hill County, and it culminates in Congressman Johnson getting legislation passed to bring electricity to rural Texas after the Depression.

Jane Ciabattari: In what ways might LBJ be a quintessential Texan?

David Biespiel: Oh, Jane! It would take a five-volume biography to answer this question. Thankfully, Robert Caro is on the job. Johnson was born in 1908, not forty years after the end of the Civil War. On the one hand, growing up dirt poor in rural Texas, his was a nineteenth century education. On the other hand, he’s an important leader in the middle of the twentieth century in the U.S., principally as a New Dealer. That’s Texas, in a nutshell. Right? The thing about Lyndon Johnson few people know, or remember, is that, in 1928, after completing his freshman year in college, he took a teaching job in Cotulla, Texas, a small farming and ranching town about halfway between San Antonio and Laredo. He taught fifth, sixth, and seventh graders at the Welhausen School, which, in the segregated Texas of that time, had been established primarily for the Mexican-American children of Cotulla. Seeing a lack of extracurricular activities at Welhausen School, Johnson organized his young students into athletic teams and bought equipment for them. He arranged for them to compete with nearby schools and because the school had no buses he was able to find those few car-owners to help take the kids to track meets and debate competitions in the region. President Johnson recalled the significance of his year in Cotulla, when he signed the Higher Education Act of 1965. He explained how his teaching experience affected his commitment to expanding educational opportunities to all students. “I shall never forget the faces of the boys and the girls in that little Welhausen Mexican School, and I remember even yet the pain of realizing and knowing then that college was closed to practically every one of those children because they were too poor.” The Welhausen School wasn’t integrated until 1970. Here then is a portrait of Lyndon Johnson as the quintessential progressive Texan of an earlier era, understanding that education was the root and route for success for minority communities.

The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas by Monica Muñoz Martinez

For some, the true meaning of Texas is its Mexican roots, and therein lies the premise of this portrait of race, power, prejudice, and government brutality in the state. Martinez exposes how the famed (myth-drenched) Texas Rangers, in the early 20th century, murdered hundreds of ethnic Mexicans living in Texas, many of whom were American citizens. Operating in remote rural areas, officers and vigilantes knew they could hang, shoot, burn, and beat victims to death without scrutiny. It’s a historical record of white supremacy on the borderlands.

JC: In 1918, Martinez writes, a father looking for his son knew that “when ethnic Mexicans disappeared after being arrest, the prisoner’s remains were often found hidden in the groves of mesquite trees in the rural Texas landscape.” How would you say the role of law enforcement in government brutality stands today in Texas?

DB: I should say that I haven’t lived in Texas in nearly forty years. But, it has lived in me. Others would surely be able to answer this question with more examples and specificity. Generally, I can say that the problems of systemic police violence against minority communities across the country are no different in Texas. Of course, Sandra Bland is a name everyone should know. In 2015, she was found hanged in the Waller Country jail, three days after she was arrested during a traffic stop. When a video Ms. Bland had taken surfaced after she died, the images showed the world the violent encounter as Ms. Bland had seen it: a close-up view of the face of the state trooper, Brian T. Encinia, contorting in anger as he pulled out a stun gun and shouted at her to get out of the car. “I’m going to light you up!” he yelled his voice growing hoarse. So, there you have it.

Molly Ivins Can’t Say That, Can She? by Molly Ivins

Although Texas’ reputation as a red state is well-established, its liberal bona fides have deep roots, too. “Why write fiction,” Texas political reporter Molly Ivins once asked, “when you can cover the Texas Legislature?” Although some of the historical figures from this selection of Ivins’ political columns might no longer be on the scene, these affable broadsides against right wing, good-ol’-boy bubbas of Texas government, business, and lobbying are essential reading for anyone wanting to get a fresh look at what liberalism with a Texas accent sounds like.

JC: Who was your favorite Molly Ivins target? Shrub?

DB: The thing about the Ivins and Bush families is this: they were both residents of the same ultra-wealthy Houston neighborhood, River Oaks. That’s where Molly Ivins grew up and from where she rebelled. I write about River Oaks in my new book. Molly Ivins was an equal-opportunity political slayer. She had no patience for those good-ol’-boy networks of state politics, Republican or Democratic bullshitters, in and around the Texas Legislature in Austin, known to most as “the Ledge.” She had special, shall we say, affection for Bob Bullock, a Lt. Governor of Texas, who’d been in the legislature since the earth cooled. She called him, Lite Guv. Same for former Governor Rick Perry, who she nicknamed, Governor Good Hair. Mostly, she called out the hip-deep, double and triple crossing system of open bribery of Texas politics. How corrupt? Two examples: In one stretch of years, five of the last seven Speakers of the Texas House of Representatives were indicted for one thing or another. (Well, to be fair, one of those Speakers was not indicted per se. He was shot to death by his wife. She was indicted, but not convicted. Because, as Ivins puts it, “in Texas we recognize public service when we see it.”) Another example: a state rep took a $200 bribe from the chiropractic association lobby to vote for a bill favoring chiropractors. When the rep voted against the bill, the angry chiropractor lobbyist wanted to know why. Said the member: “The doctors’ lobby gave me $400.” If you took all of the fools out of the Texas Legislature, it’s often said, it would no longer be a representative body. I could go on.

The Last Picture Show by Larry McMurtry

Here’s one novel—and there are a fistful of recent ones that could easily make a second list. I can’t say I enjoy his westerns, but this satiric McMurtry novel, practically a novella, gives you as good feel as any for the monotony and insularity of a small Texas town. It does so without hiding something else I love about this book, the underlying Texas tension between Saturday night sex and Sunday morning salvation.

JC: McMurtry conveys the boredom of that small Texas town in the 1950s, along with the football and pool playing, the playing around. Who’s your favorite character?

DB: They’re all lost. Aren’t they? I suppose Duane Moore is the one I have the greatest interest in—in the ways he’s torn about being in and being from a place, which is a subject of my book, and a recurring theme of Texas literature. McMurtry must have a similar interest in Duane, too, because he’s written more books about this character, Texasville, Duane’s Depressed, and others. Peter Bogdanovitch’s film adaptation, I think, has lessened the book’s appeal—in part because the film has been so successful and iconic. But, in 1970, when the Bogdanovitch and his crew came to Archer City, Texas, where McMurtry was from, to film the movie on location, the townspeople were hostile. And, not just the townspeople. I’ve read that McMurty’s father, speaking about his son Larry, said to one of the crew, “You pour kerosene on him, and I’ll light the match.”

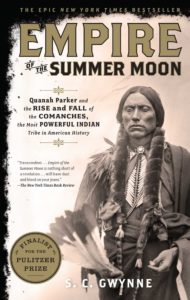

Empire of the Summer Moon by S. C. Gwynne

This is an historical account of the four decades of battle between Comanche Indians and white settlers for control of the American West that culminated in the Texas Panhandle. The book centers on two remarkable figures: pioneer woman Cynthia Ann Parker and her mixed-blood son, Quanah, who became the last and greatest chief of the Comanches. I’ve read this book several times now; it’s riveting.

JC: Comanche leader Quanah Parker’s story bridges a major transition in U.S. and Texas history, and two cultures. His mother, Cynthia Ann Parker, was the daughter of settlers kidnapped at age nine, in 1836, and and raised among Nokoni Comanches. His father, Peta Nocona, was a fierce Comanche warrior. Gwynne’s narrative offers so many vivid moments. Like this one: After Quanah surrendered in 1875, he described to his friend Miller how “the white man had pushed the Indian off the land.” He has Miller sit on a cottonwood log.

“Quanah sat down close to him,” writes Gwynne, “and said ‘Move over.’ Miller moved. Parker moved with him, and again sat down close to him. ‘Move over,’ he repeated. This continued until Miller had fallen off the log. ‘Like that,’ said Quanah.”

What makes this such a gripping history? Is it Gwynne’s narrowing his focus to Quanah and his mother?

DB: You’re characterizing the book in a way that makes a lot of sense to me. I appreciate how you put it. Yes, I agree with you. Gwynne’s gift is to get history told through the details of the human body. Know what I mean? Inch by inch down the log. Gwynne is a historian who believes that history should be dramatized as way of recording it. Focusing on Quanah and his mother, Gwynne amplifies the history of the U.S. government and the Republic of Texas to stop the Comanches under Quanah’s leadership. Don’t you think? In that way, Gwynne’s story-telling gives voice to the native peoples and their place in American history. More so, in my view, than famous historical novels like those by Larry McMurty or Hollywood Westerns.

Trip to Bountiful by Horton Foote

One meaning of Texas is fetishizing nostalgia. Horton Foote’s emotional 1953 play tells the story of Carrie Watts, an elderly woman who longs to return to her beloved hometown of Bountiful, Texas, one final time before she dies. Her son and daughter-in-law forbid her to leave Houston, although Carrie and daughter-in-law are constantly butting heads in the Watts family’s two-room apartment. When Carrie escapes on a bus, she finds the truth of memory is beautifully difficult. The film of this play, directed by Bruce Beresford, is eye-candy for anyone…well, longing for Texas and longing for home.

JC: I also found Foote’s Talking Pictures, set in 1929 and featuring a pianist for silent movies who is about to become obsolete and her fourteen-year-old son, an enlightening portrait of small-town Texas. But your last sentence begs the question, do you miss Texas? You’ve lived in Portland how long now? Would you ever go back?

DB: I didn’t grow up in a small Texas town like those highlighted on this list: Johnson City, Archer City, “Bountiful.” Instead, I grew up in a tight-knit neighborhood, Meyerland, of a major Texas city. For years, after I left Texas, I half-assumed I’d return, though I was also half-certain I would not be welcomed back. My new book tells that story—of the rise and fall of a Jewish boyhood in Texas. It also tells the story of Meyerland, the historic Jewish section of Houston where I lived and attended school at Beth Yeshurun, which is the largest conservative congregation in North America. This is my twelfth book. Like all of my books, so far (I think), it explores questions of meaning: where we find it and what it offers us. Recently, Meyerland has been devastated by three five-hundred-year floods in three years, including Hurricane Harvey, the worst flood in Texas history. I’m inclined to say that telling this story about Texas in A Place of Exodus is one way I’ve gone home. And, I try to elevate the importance of the question, What do we mean when we speak of the beauty, mystery, and community of home? The thing about going home is this: Too often we lose sight of the fact that the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves are always in need of a fresh reckoning.

Dazed and Confused, dir. by Richard Linklater

I’m just a little younger than the characters of this near-cinema verite, but I love how much the movie says about my own high school experience growing up in Texas and about the meaning of wanting to leave Texas—all rendered in the film on the last day of school in 1976. Bongs, bell-bottoms, rock and roll. Sidestepping nostalgia, Linklater’s film is less about the so-called best years of our lives, than the excitement of waiting for something to happen.

JC: Dazed and Confused skipped the drama and highlighted the experience of hanging out. Knocking over mailboxes, drinking, fooling around, fighting (and it brought us Ben Affleck, Matthew McConaughey and Parker Posey). How does it compare to your own the meaning of wanting to leave Texas?

DB: I left Texas to escape what I took to be the insularity, the monotony, and the rectitude of Jewish Meyerland. I left in order to think about anything else but all that, to endure any other aspects of life, to go anywhere else. I left not because I didn’t have community, or love, or a home. Not because I thought of religious faith as some fact, some arrival, some certainty the way people do when they use the word faith sometimes. I didn’t have faith in faith, is what it was. Because I didn’t have faith in any of it—faith in the rituals to praise God, in the possibility of God, recovering any of that in the future or the belonging that went with it. I recognize that for some, all that possibility is the allure. But that’s what I was repudiating. Over time, like a lot of people, I’ve become a person who views religion as a machinery of thought, and like any machinery it can be used for noble callings and it can be used for wicked ones. I’ve become a person who is not prepared to live under the insinuation that the universe is designed with human beings in mind—or worse, that there is a heavenly plan into which everyone fits, whether they want to or not, or know it or not. A secularist like me is comfortable with uncertainty, curiosity, inquiry, trial and error. In the end I simply prefer my ignorance to the other guy’s dogma. I have lived in over a dozen houses or apartments since I left Texas nearly forty years ago, perhaps been a different person in each one, and yet the memory of my response to why I left Texas is one of the pillars I associate with home. Texas may not be the center of my physical universe, but it is the center of my cognitive one. I wanted to leave Texas to conquer a different world, with all its perils and rewards, because of a powerful, evolutionary desire to feel, paradoxically, at home.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·