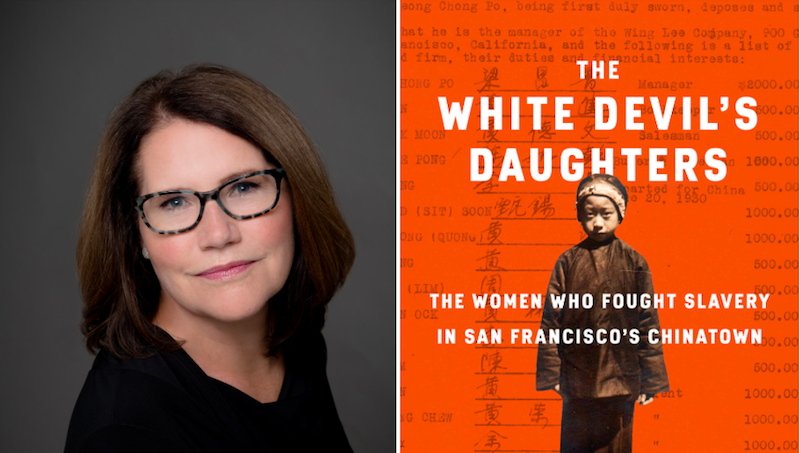

Julia Flynn Siler’s The White Devil’s Daughter is published this month. She shares five books of narrative history.

A Distant Mirror by Barbara W. Tuchman

I first read this as a teenager and was awed by how Tuchman immersed her readers in 14th century Europe. She’s better known for The Guns of August, but this is the book that made me fall in love with narrative history. (Her essay collection Practicing History is also on my shelf.)

Jane Ciabattari: Tuchman won her first Pulitzer for The Guns of August, her second for Stilwell and the American Experience in China, before writing A Distant Mirror, her book about “the calamitous 14th century,” as she calls it. She structures her story around Enguerrand de Coucy VII, whom she calls the “most experienced and skillful of all the knights of France.” She fills her narrative with vivid scenes describing wars, the Crusades, the Black Death, relations among European nations, the sharp economic contrast between aristocracy and peasantry. I’m struck by the way she contrasts the life of the few at the top, the 14th-century nobility, which “seemed full of brilliance and adventure,” with what awaited the masses: “a succession of wayward dangers; of . . . pillage, plague, and taxes; of fierce and tragic conflicts, bizarre fates, capricious money, sorcery, betrayals, insurrections, murder, madness, and the downfall of princes; of dwindling labor for the fields, of cleared land reverting to waste; and always the recurring black shadow of pestilence carrying its message of guilt and sin and the hostility of God.” Are there specific passages that stay with you?

Julia Flynn Siler: As a teenager reading A Distant Mirror, I could feel and see the fine particles dust kicked up during the jousting matches she described—Tuchman’s writing was so evocative to my fifteen-year-old imagination. Now, her somewhat old-fashioned prose doesn’t quite stir me in the same way, and I’m aware that academic historians haven’t always been her fans. But I still appreciate Tuchman’s ability to synthesize beautifully information and her gift for recreating a distant world. with the delicate brushwork of a watercolorist: “When the last of the Coucys was born, his country was supreme, but his century was already in trouble. A physical chill settled on the 14th century at its very start, initiating the miseries to come. The Baltic Sea froze over twice, in 1303 and 1306-07; years followed of unseasonable cold, storms and rains, and a rise in the Caspian Sea. Contemporaries could not know it was the onset of what has since been recognized as the Little Ice Age…” In a few, short sentences, she’s described Medieval climate change and set the scene for the upheaval ahead.

Common Ground by J. Anthony Lukas

A monumental work of narrative history, following the lives of three Boston families as they live through a tumultuous decade of desegregation. I read this a few years later, as a college student, and it deeply influenced my thinking about how to tell a sweeping history through individuals.

JC: Lukas wrote, “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal. . . . What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, white society condones it.” And he shows us in this groundbreaking book by telling the stories of individuals. How has that approach influenced your work in The White Devil’s Daughters?

JFS: Lukas’s decision to tell the story of school desegregation through three very different families deeply influenced my thinking about how to tell a sweeping story of immigration. My book also explores how white society was deeply implicated in the crowded and violent ghetto of Chinatown, which white institutions helped create and maintain, and profited from. I show this through the stories of individuals. I follow human traffickers, as they brought girls and women from China to San Francisco, worked closely with corrupt officials (some of whom even owned and operated a brothel there nicknamed “the Municipal Crib.”) But I also follow the movement of a small group of women who fought against some of the most egregious of the injustices they saw taking place, as well as a crusading Chinese newspaper editor. I especially admire the way Lukas handles issues of race and class, since my book similarly examines the collision of gender, race, and faith in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

Bury the Chains by Adam Hochschild

It was tough to decide between this book on the British abolitionist movement or his monumental King Leopold’s Ghost, about the exploitation of the Congo by Belgium’s King Leopold. Hochschild has such a distinctly measured and resonant voice and helps recreate these far-off worlds with finely observed details and a measured authority.

JC: Bury the Chains focuses on abolitionist leaders like MP William Wilberforce, John Newton, the slave ship captain who found God and wrote “Amazing Grace,” Olaudah Equiano, the Igbo freedman who wrote bestselling books, and Thomas Clarkson, founder of the anti-slavery movement in 1787. “It was the first time in history,” Hochschild writes, “that a large number of people became outraged, and stayed outraged for many years over someone else’s rights.” How did this book influence your thinking about writing about social change?

JFS: I share an interest with Hochschild in historical moments when people experience an upsurge in empathy. In Bury the Chains, he explored what motivated the leaders of Britain’s abolitionist movement, while the question I sought to answer was why a group of mostly middle-class white women in 19th-century San Francisco decided to defy the conventions of their time and the widespread racism and violence towards the Chinese by setting up a safe house for Chinese women who’d been trafficked into prostitution. These women’s motives varied, and it is through their individual stories that we follow and begin to understand that leap of empathy that motivated them to defy their husbands and fathers and many of the people around them to work towards social justice. They encountered arson threats, sticks of dynamite placed around their mission home, smashed windows, and a constant threat of violence, but they persevered. It was a bit like a Victorian-era #MeToo movement: women standing up for other women.

The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson

A masterwork that illuminates the migration of some six million African Americans from the South to the North in the twentieth century by focusing on the stories of individuals.

JC: The Warmth of Other Sons won the National Book Critics Circle nonfiction award. Wilkerson focuses primarily on Ida Mae Brandon Gladney, George Swanson Starling, and Robert Joseph Pershing Foster, as she tells the story of the six million who were part of the Great Migration north during the twentieth century. She conducted more than 1,200 interviews while working on the book. How do you think these accounts of first-hand experience influenced her ability to tell such a gripping and detailed story?

JFS: Wilkerson’s interviews and deep, empathetic research allowed her to tell the story of these three individuals with an intimacy that is rare in nonfiction. Those first-hand accounts are at the heart of why this is such a great book, and the rhythm and beauty of her language—reflecting her extensive interviews—is on the same level as that of our most gifted novelists. But perhaps the most striking thing about her epic, 622-page work is the sheer blazing ambition of it—her attempt to capture the vast migration of millions of people over 55 years. It was as if she’d taken to heart Hermann Melville’s words in Moby Dick: “To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme.” She chose the mighty theme of the Great Migration, and cast her characters brilliantly, weaving it all together with lyrical writing. It’s rightly considered a new classic of nonfiction.

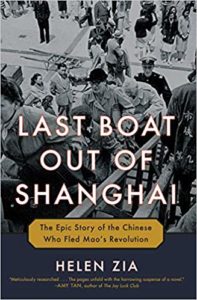

Last Boat Out of Shanghai by Helen Zia

Published earlier this year, Zia tells a powerful story, subtitled “The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Fled Mao’s Revolution,” by braiding together the stories of four individuals who managed to escape just before the Communist takeover.

JC: Zia’s mother, Bing Woo, was given up for adoption and then joined the million or so to fled Shanghai, which was, at the time of Mao’s revolution, China’s “most modern, cosmopolitan and populous city.” Zia embeds her personal story in a complicated narrative of monumental change in China and its effects on several other families. I know from reporting trips to Shanghai how difficult it is even now to retrieve these stories, how much was lost and never spoken about. And yet she makes her story vivid and clear. How?

JFS: Yes. One of the many strengths of this book is Zia’s ability to write clearly about a subject as complex as the Chinese revolution and the far-flung diaspora it produced. The revolution and its aftermath are a complex, traumatic story and one that many exiles prefer to keep locked away in their memories. It is a tribute to Zia’s stunning research that she is able to piece together the journeys of these four different characters. Like Hochschild, Lukas, and Wilkerson, Zia has also done a masterful job of “casting” the characters in her nonfiction novel—including one who, as it turns out, is her mother. It is probably no coincidence that all the authors who’ve most influenced me had honed their craft as journalists before they turned to writing narrative nonfiction. Zia’s book is beautifully crafted, with an ending that stayed with me long after I closed the book.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·