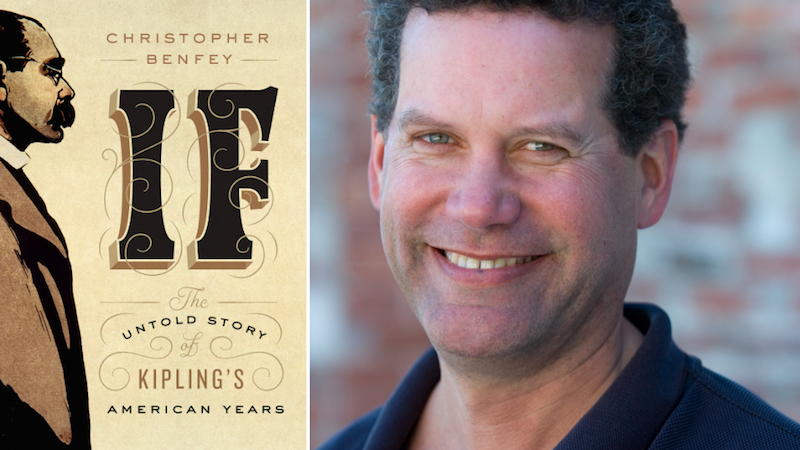

Christopher Benfey’s If: The Untold Story of Kipling’s American Years is published this month. He shares five books from Kipling’s New England.

Captains Courageous by Rudyard Kipling

If you read this book as a kid, you probably remember it as an adventure story. Spoiled brat falls off liner boat, is rescued by a Portuguese-American fisherman out of Gloucester, Mass, and learns through grit and tough love to be a man. Kipling developed the idea for the book through conversations with William James, he of the “moral equivalent of war.” But the book is actually gloriously visual, a series of Impressionist paintings of the changing sea in shifting light. Kipling lived for four years in Vermont, from 1892 to 1896, where he wrote The Jungle Book and Captains Courageous, and he worked hard to get the details right in his adopted land.

Jane Ciabattari: How did Kipling’s time in New England influence the look of Captains Courageous? (And his own fishing trips?)

Christopher Benfey: Kipling read all he could about fishing in the North Atlantic, both government reports and old ballads, but he wanted to feel it in his muscles and see it with his own eyes. He talked his way onto a fishing boat in Gloucester, promptly got sick from the smell of rotting cod, but—in typical Kipling fashion—persevered. He also listened. He had a gift for mimicry and he was determined to have his diverse cast of Americans talk the way Americans talk.

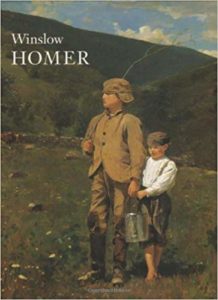

Winslow Homer by Nicolai Cikovsky Jr. and Franklin Kelly

Look closely at three of Homer’s amazing paintings of fishermen: The Herring Net, The Fog Warning, and Lost on the Grand Banks. They form a dark sequence of work, warning, and catastrophe, as the Mother Ship slips from view in the fog. These paintings are the true source of Captains Courageous, both the unbelievable risk of the fisherman’s life in the North Atlantic and the staggering beauty of ocean, fog, and changing light.

JC: Do you have a favorite? And how does it connect with the Kipling work, which is also permeated by fog?

CB: I particularly love The Fog Warning, in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The fisherman in his boat, laden with halibut, is pulling hard on the oars in rough seas. We can see the thunderstorm forming on the horizon hovering menacingly over the distant Mother Ship. Will he make it? Will we make it? There’s an existential sense of threat in the painting that also pervades Kipling’s novel. For Kipling and other writers of his generation—think Conrad and also Stephen Crane’s “The Open Boat”—being lost at sea was the ultimate picture of desolation, of being alone in an indifferent universe.

The Country of the Pointed Firs by Sarah Orne Jewett

Kipling told his friend Jewett that this book was what he was aiming for in Captains Courageous. Jewett’s not-quite-novel is an elegy for a vanishing Maine coastal world. The shipping trade has moved south and west; the fisheries are declining; the young men are abandoning New England for California and the West. Jewett’s narrator arrives in a small coastal village to get some writing done. She rents an abandoned schoolhouse and goes to work, summoning up the lost history and dreams of the locals. The book is indescribably beautiful in a quiet, meditative way, and beautifully written.

JC: It’s intriguing to learn that Kipling and Jewett were friends. And that Jewett’s elegiac, sometimes melancholy novel set the mood for Captains Courageous. Jewett structures the novel in vignettes, with the narrator making a return visit to a coastal town in Eastern Maine. “After a first brief visit made two or three summers before in the course of a yachting cruise, a lover of Dunnet Landing returned to find the unchanged shores of the pointed firs, the same quaintness of the village with its elaborate conventionalities; all that mixture of remoteness, and childish certainty of being the center of civilization of which her affectionate dreams had told,” she writes in the opening section, setting up this summer of visits with the fisherman of the area, laconic storytelling elders. Are these characters an influence the New England fisherman under whose tutelage teenaged Harvey Cheyne comes to manhood?

CB: Yes, absolutely, though in Kipling’s novel the fishermen are younger and still vigorous. Both Jewett and Kipling loved the resilience of these fishermen, their openness to experience and risk, their reverence for the powers of nature. Both writers felt that a way of life was being lost in the face of rising industrialism and wanton capitalism. They were also intensely visual writers: the pointed firs, the swirling sea.

North of Boston by Robert Frost

What a very different writer did with the decline of New England during the 1890s, when Kipling, like Frost, was living in Vermont. These are short stories in verse, really, with pride of place for the excruciating “Home Burial,” in which the death of a child rips a young couple apart. The title is both literal—the child’s grave can be seen from an upper window—and figural: this home is being buried alive. The collection also includes “The Death of the Hired Man,” with its famous dueling definitions of home: “Home is the place where, when you have to go there, / They have to take you in.” “I should have called it / Something you somehow haven’t to deserve.” Frost and Kipling are obsessed with getting the sounds of New England voices right.

JC: Not to mention “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall.” Did Kipling ever write anything with that sparseness?

CB: Kipling’s “If—” has roughly the same stature in the UK that “The Road Not Taken” has in the US. Both poems celebrate going your own way; both consist of advice to the young. People all over the political spectrum quote Kipling and Frost. Does “Mending Wall” support Trump in his wall fantasies (“Good fences make good neighbors”) or undermine him (“Something there is that doesn’t love a wall”)? Kipling isn’t as sparse as Frost when he tells us to treat those two impostors, Triumph and Disaster, just the same. Another poem beginning with “If,” written after Kipling’s son died in World War I, has a devastating sparseness. It is spoken by the dead young soldiers. “If any question why we died / Tell them because our fathers lied.”

Essays by Ralph Waldo Emerson

Kipling kept a photograph of his beloved Emerson on his writing desk. Emerson’s imprint is everywhere in his work, most famously, perhaps, in “If—,” which is a kind of versified version of Emerson’s signature essay “Self-Reliance.” Emerson’s epigraph to that essay—“Cast the bantling on the rocks, / Suckle him with the she-wolf’s teat”—probably inspired The Jungle Book, with baby Mowgli nursing in his adopted wolf family.

JC: How did Kipling discover Emerson, and what made him such a major influence?

CB: We have to remind ourselves that Emerson was Prometheus for Kipling’s generation, a great liberator, and not the Polonius we sometimes think he was. Nietzsche loved Emerson. All the avant-garde European writers, from Baudelaire to Rilke, read Emerson with reverence. And Kipling came out of that kind of background; his uncle was the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones, and he knew the socialist writer and artist William Morris when he was growing up. Emerson told his readers to trust themselves, to ignore conventions. “Whoso would be a man must be a nonconformist.” Kipling’s heroes—Mowgli, Kim, and the rest—invented their own codes, lived by their own rules.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·