Diane Cook’s novel The New Wilderness has just been published, and already it’s been longlisted for the Booker Prize. (The shortlist will be announced September 15.) She shares five books about wildernesses.

The Call of the Wild by Jack London

Told from the perspective of Buck, a sled dog in Alaska who is reunited with his own wildness. No one told me to read this book when I was younger. I think it’s because I’m a girl. I finally read it in my late thirties, when I was writing my novel. But I wish I’d read it a hundred times before. The last page is the best page ever written about being a wild animal, which also pertains to being a person in a community.

Jane Ciabattari: I can’t resist quoting from that last page:

In the summers there is one visitor, however, to that valley, of which the Yeehats do not know. It is a great, gloriously coated wolf, like, and yet unlike, all other wolves. He crosses alone from the smiling timber land and comes down into an open space among the trees. Here a yellow stream flows from rotted moose-hide sacks and sinks into the ground, with long grasses growing through it and vegetable mould overrunning it and hiding its yellow from the sun; and here he muses for a time, howling once, long and mournfully, ere he departs.

But he is not always alone. When the long winter nights come on and the wolves follow their meat into the lower valleys, he may be seen running at the head of the pack through the pale moonlight or glimmering borealis, leaping gigantic above his fellows, his great throat a-bellow as he sings a song of the younger world, which is the song of the pack.

What tips Buck into wildness? And what does it take for we humans to reach this tipping point?

Diane Cook: I think it’s Buck’s search for a home, a place to be, a sense of belonging to someplace or someone(s) that lets his instinct bloom again until he is whole, the creature he was born to be, not merely trained to be. I think humans look for that same thing. A place or people with whom you can be what you were born to be, not molded to be. I think this community you create isn’t always full of who you think it will be. It isn’t always where you think it will be. You have to be open to it. Not count anyone out. You discover who is there when you find yourself saying things you recognize as true, maybe for the first time.

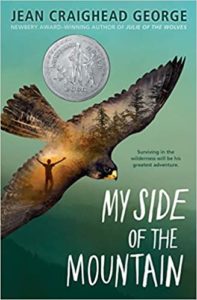

My Side of the Mountain by Jean Craighead George

No one told me to read this one either. Also, I think, because I’m a girl. I certainly knew about it, but I guess I was reading the books for girls. The funny thing is that it’s written by Jean Craighead George, a woman (among other things). It follows Sam, a boy who absconds to the Catskills to live the woods, in a tree, for a year. It’s pure adventure wilderness fantasy. I read it in my late thirties and I wished I had read it a hundred times already.

JC: Sam smokes trout, makes acorn pancakes, hangs out with his falcon, Frightful, and a weasel he calls Baron. He’s worked to learn survival skills to help him through as he holes up in a hemlock tree, where he’s made a snug cave with “a bed made of ash slats and covered in deerskin.” In the opening scenes he faces a blizzard. His immersion in wilderness is seductive. Do you think that is especially appealing during our pandemic?

DC: I can’t remember now why Sam goes away, if there is any reason other than pure adventure. Perhaps a feeling that he doesn’t belong in the life he was living in the city. Something about it felt like a trap. I definitely think people feel the need to escape right now. They feel scared and trapped and out of control. The social contract we all agree to abide by when we live among one another seems altered. Like, “Well, I didn’t agree to this.” So we look to leave civilization. We romanticize escape and solitude, but generally I don’t think we’re meant for it. Not in the long term. Not really. It reminds me of Walden. The big take away from Walden for me is not that he went to the woods to live deliberately, but rather that he eventually left the woods and returned to civilization. Once he was there long enough he realized he didn’t need to stay. That, perhaps, he shouldn’t stay. Even that it would be wrong to stay. That it would betray something essential about being a part of the fabric of the world. We learn something when we leave the world behind, and what we learn often draws us back.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel

Wildernesses are often portrayed as places of risk and danger, of unknowns, a place we are not a part of, our absence being what makes it wild. But wilderness is really just an idea and I think Station Eleven flips it on its head. Set in a post pandemic wasteland, this end of the world book is a lot more inviting than most end of the world books and I think that matters. There’s danger and risk in wild spaces but there is also teeming life and a kind of nourishment, an inherent future. Something grows from it. I think letting characters have something more than survival in an end of the world scenario, have something as fragile as happiness, is a wild idea.

JC: How does Mandel create that sense of an “inherent future”?

DC: In survival there is an inherent future, but Mandel is arguing that it must be a future worth having. I think in common end-of-the-world narratives survival is so brute. And so much emphasis is about the action of the end of days. Mandel looks past the big event to not just what comes next, but what is down the line, past the point where basic existence is the goal. Not simply how to keep living, but what makes life worth living. That felt new to me to move the end-of-the-world narrative past fear toward something bigger and more sustaining. And of course, in the middle of the book she jumps the story back in time to those real end days, and when that happened I just wept for them. It was so effective because I cared so much by that point.

Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill

I sat next to novelist and bookstore owner Emma Straub at an event in the before-times, and she asked me a very similar question to this one—what were my most influential or favorite books about the wilderness. I don’t know if I was panicking or being brilliant but I said Dept. of Speculation because there is a wilderness of the mind that is somehow captured on the page and that was really important for me to read. A lot of great books have this quality. Some books take on a subject and uncover wildernesses. Like The Golden State by Lydia Kiesling or The First Bad Man by Miranda July, which unveil wildness in motherhood. If I remember correctly, Emma mentioned Lauren Groff’s Florida as a wild text for her. And I’d agree. Look at me cheating on this question and mentioning all sorts of books!

JC: Offill is especially poignant in describing the mother-daughter bond: “But the smell of her hair. The way she clasped her hand around my fingers. This was like medicine. For once, I didn’t have to think. The animal was ascendant.” You focus intensely on that bond in The New Wilderness, opening with the loss of a child, building the ties between Agnes, a child who is wasting away in the city at age five, and her powerful mother Bea, who carries her into the Wilderness State to save her life. What makes motherhood a wilderness?

DC: I think in how difficult it is to describe, to pin down, to write about, to capture. It is bewildering. It is instinctual and guttural. It seems unknowable. But I think what makes it seem that way is its vastness, the diversity of its ecosystem. The spectrum of motherhood is so broad. And just like with wilderness, we have this very rigid idea about what it is, and what it isn’t. Wilderness is essentially a construct and the idea of how a mother should be is one, too.

In the Distance by Hernan Diaz

A Swede finds himself in early California by accident and must travel against the tide of pioneers, to return east. He lives off the land, even lives in the ground at some point. This book is incredible. I read it right after I finished writing The New Wilderness. They’re extremely different books but what they share is very specific and made me feel like I was returning to a precious place and seeing it with new eyes. The way the narrator can pass in and out of mountains in a day or two so perfectly captures the desert. The mountains are islands in a sea of dryness and seeming scarcity. But how much bounty he finds in that scarcity! It was also wonderful to see brain-tanning feature prominently. It was like coming home.

JC: Håkan Söderström and his older brother Linus are sent to America from Sweden in the 1850s, in search of a new life. They lose each other, and Håkan must walk across America, east from California, to find his brother. Imagine the frontier landscape from the point of view of a newcomer who doesn’t recognize railroad tracks or the difference between one side or the other in Civil War uniforms, who traps and forages for sustenance (as do your characters in the New Wilderness). The Pulitzer committee, in naming the book a finalist, called it “a portrait of radical foreignness.” Is the point of view the key to this book? The detail? What?

DC: I think the POV is key, and also what Håkan views and when he views it. That trinity of writing. He views this arid, harsh, seemingly empty land at this point in history and presents it through new eyes. It’s a story we think we know–a pilgrimage—but through his eyes we see how ugly and strange it all is. The grotesquerie of what happened to the land and the people indigenous to it is really on display with him as our guide. It’s also an American pilgrimage told in reverse. Håkan isn’t looking for a new home, he is looking for his old home, in his brother. Something of comfort. He searches while passing the lines of wagons full of pioneers who are looking for something new and leaving everything they knew behind. There is an indictment there that seems to go beyond just their terrible behavior out west. It’s such an astonishing and weird book.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·