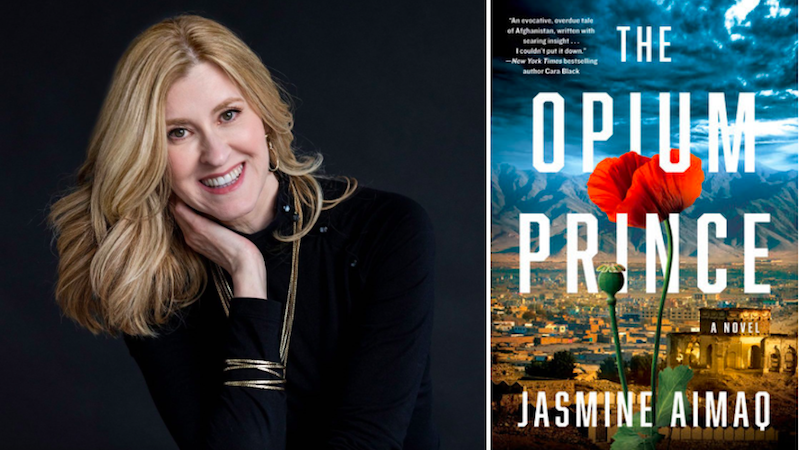

Jasmine Aimaq’s The Opium Prince was published last week. She shares five books about the “real” Afghanistan.

West of Kabul, East of New York by Tamim Ansary

When I read the first pages of this book, I shouted out in amazement because I found experiences identical to mine. After moving to the US, Ansary had a schoolteacher ask him, “Where are you from, Afghanistan?” not as a literal question, but as a metaphor for “Did you grow up on an alien planet?” At age eleven, I was asked the same thing for the same reason. This is a wonderful read about living your life between drastically different cultures.

Jane Ciabattari: Ansary was raised in Kabul by two educators (his father was Afghan Pashtun, his mother Finnish American), then came to the U.S. to high school in Colorado, attended Reed College, settled in San Francisco. His travels in Iran and then back to Afghanistan after 9/11 infuse this book with the tension between two cultures. How does your own journey compare?

Jasmine Aimaq: My experience has some parallels but is also different. One similarity is that our fathers had high positions in Afghan society, and another is that our mothers were Western. But my home life in Kabul was not as Afghan as Ansary describes his and I never went to Afghan schools. My mother is Swedish and is a trained interpreter who is fluent in French. My father, who did not practice Islam at all, was educated at the French Lycée Esteqlal in Kabul and grew up bilingual. Since French was the only language my parents had in common, that’s what we spoke at home, and I went to French schools until the 7th grade when we moved to America. There was also a lot of Farsi and Swedish in my life, and German because that’s where I was born. So I was connected to many different cultures at once.

We left Afghanistan when I was eight, moving to England, then to Germany, and finally the US. Until I was twelve, when people asked me where I was from, I would usually reply that I was French. I thought that was correct. I didn’t understand the concept of nationality at all and I never thought about it. Nobody I met had ever heard of Afghanistan, either. (“Is that in Africa?”) Although we spent every summer in Sweden, I hadn’t yet lived there, so that did not sound right either.

Things changed after the Russians invaded Afghanistan in 1979, a few months after my family had moved to the US, where my aunts and uncles also settled. Suddenly Afghans were described on the news as freedom fighters (see: Reagan era) and I was now considered “interesting” in school. It was confusing and strange. Years later, after 9/11, people would randomly and solemnly tell me how sorry they were that the Americans were invading “your country.” It felt patronizing. They were making big assumptions about my views on that subject.

Over time, I have looked back on various incidents in my life and understood that I’ve been on the receiving end of bigotry, as was my father. Although I am most at home in America, I feel like both an insider and an outsider everywhere. That’s not necessarily a bad feeling—I can’t say I have ever missed having a firm national identity. It does seem hard for other people to accept, however. They often insist that I must be something that fits with their framework of the world and their understanding of themselves. (“But what are you? Don’t you feel rootless? What language do you dream in?”) The cultural awkwardness does not come from inside me; it comes from the importance others place on a particular category.

Letters from Afghanistan by Eloise Hanner

After 9/11, I longed for books that recalled the old Afghanistan, and in 2003 this came along. It shows life in 1970s Kabul through the eyes of an American woman who writes letters home to her mom. It is so wonderful for me because I think Rebecca must have seen things very much like Eloise Hanner did, and it also reminds me of my Aunt Eleesa, who lived near us in Kabul and was the first American I ever met.

JC: Hanner was a Peace Corps volunteer in 1971, before the Soviet invasion, before the Taliban. After 9/11 she pulled out her letters (the sole communication with her family, as she had no telephone), finding it difficult to reconcile the “nightly news clips of the bombings and machine-gun toting Afghans” with her own experience of “the amazing bazaars, the Kuchi tribes, the herds of fat-tailed sheep that kicked up dust along our street at dawn,” the kabob shops, camels, and “Hazaras carrying heavy loads on their two-wheeled wooden carts.” Which passages resonate most with your own memories and experiences?

JA: Hanner’s most wonderful description is of a money-exchange shop. It is quintessentially Afghan, with drawers and stacks of bills everywhere, and the shop-owner negotiating with his clients and understanding his own seemingly chaotic system with no trouble. Her descriptions capture so much of what stands out in comparison to the West. The hardest thing to convey, however, is the way that tension and peace coexisted. In one way, Afghan society in the 1970s was very peaceful. Stranger-on-stranger crime and gang violence didn’t really exist, and people were extremely polite. You were safe in Kabul in a different way than in many Western cities. But there were also tanks in the street, a coup d’état, and of course significant rates of domestic violence behind closed doors.

Drugs in Afghanistan: Opium, Outlaws and Scorpion Tales by David Macdonald

This is not just another book about the drug trade. It’s a riveting first-person account that offers in-depth knowledge about the changing role of opium in Afghanistan and beyond, including history, production, and consumption, and touches on both intimate personal stories and geopolitical events.

JC: Macdonald, a drug advisor to the UN, describes the search for the truth about drugs and their uses in Afghanistan as “an elusive enterprise often clouded by exaggeration, rumor, innuendo, myth, half-truths and a sheer lack of reliable information.” His book is both informative and vivid (his description of Mullah Akhundzada, head of Afghan’s State High Commission for Drug Control, for instance: “With his long black hair and dark enigmatic expression, his face looked remarkably similar to … Jim Morrison, lead singer of the Doors.”) Was this book useful as research for your novel, The Opium Prince?

JA: It was very useful, especially for my first draft! Originally, I had an additional subplot that included characters who manufactured heroin, and I had a lot of detail about the process, labs, and hierarchies. I edited this out, but my understanding of the opium poppy trade and its role in Afghan history is largely thanks to Macdonald’s research.

Afghanistan: A Companion and Guide

To describe this is a travel guide would be a major understatement. It’s a spectacularly photographed tome that reveals the nation’s history, geography, and culture, including art, architecture, and poetry, with chronologies and excerpts from journals, book and official missives.

JC: What period of Afghanistan’s history do you find most compelling?

JA: The one that has not yet been written. I often think about a day when the country will be at peace, with a stable regime, where radicalism is on the fringes and war is in the history books.

Earth and Ashes by Atiq Rahimi

When I heard about this novel, the author was immediately interesting to me because, like my father, he is bilingual French-Dari and went to the Lycée Esteqlal in Kabul. They’re part of an ever-shrinking group. Here Rahimi tells a powerful, universal story about fathers and sons and inter-generational understanding amid the drama of war.

JC: Earth and Ashes is a distilled novella-length book, shot through with trauma. A grandfather, Dastaguir, and and his grandson, the only survivors after their village has been destroyed by a Russian bomb, travel to the mine where the boy’s father works. How do you think Dastaguir’s weird visions, his second-person narrative, his grandson’s outbursts, and other fragments create such a powerful parable of war?

JA: Rahimi has such an interesting writing style, and his stories remind me of classical plays. He captures the constancy of war in multiple ways. Having three generations in the narrative represents the future, present, and past, for example, as well as the endlessness of conflict. The visions and outbursts create a sense of distortion and incoherence all infused with urgency, sorrow and fear, and what is war, if not those things? The story is universally about war, and at the same time uniquely about Afghanistan—and it’s also intimate, like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·