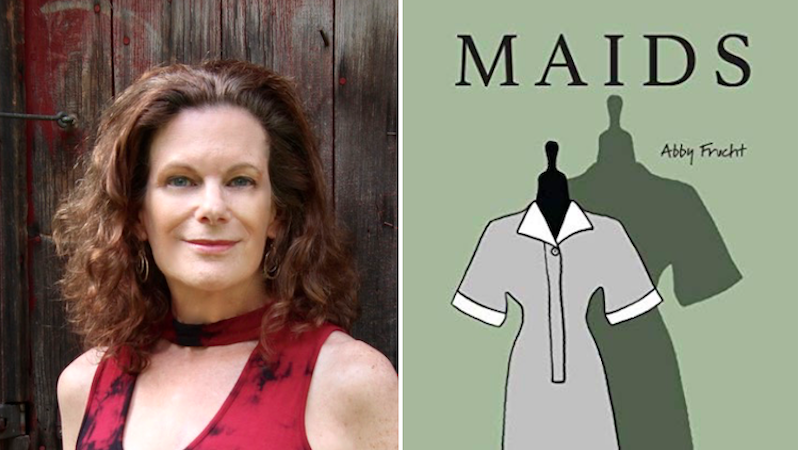

Abby Frucht’s Maids is published this week. She shares five books about the politics of women’s bodies in space, noting that these five books demonstrate a concept put forth by Carmen Maria Machado: “A house is never apolitical. It is conceived, constructed, occupied, and policed by people with power, needs, and fears. Windex is political.”

The Black Notebooks by Toi Derricotte

The twenty years of journal entries comprising Toi Derricotte’s explosive The Black Notebooks lament that the homes in our neighborhoods and subdivisions work to keep us in our places, whatever those places are deemed to be. Bone china is fortress and armament, here. Heads up at the weekly cocktail parties. Essence calls The Black Notebooks a “searing chronicle of racial anguish and personal growth.”

Jane Ciabattari: At one point in her section “The Club,” Derricotte describes moving into a majority white suburb and being plagued with insomnia, likely the result of how troubled she is by the racism unveiled when she tells people she is black. She jots down a line in the middle of the night: “Like a tree in hostile soil.” It’s such an evocative line. How does she use her voice as a poet in making these journal entries so powerful?

Abby Frucht: Mark Strand said of his first encounters with poems that they located him “in a vastness” that in his real life made him feel lost but that once he started finding it on the page “took on a shape” that pleased him by putting the world within him “in sync with the world without.” No matter how different the worlds of her readers might be from Derricotte’s, in reading her journals those same readers will understand that their most pressing, even inchoate feelings might be matched somehow with the actual objects and events around them. Such reckonings are often painful for Derricotte, and her language reflects and compels her distress, like when she writes, of the white members of a neighborhood club who lament the racist owner’s refusal to admit Derricotte and her husband: “(B)ehind him they hide their ugliness, behind his big fat ass they hide their little house and little dishwasher.” Elsewhere, like when Derricotte posits that race is a state that floats “between us, equally solid and unreal, as if our body and soul were kept apart, and, like a kind of Siamese twins, joined only by a thin cord of desire,” the poetry she brings to her Black Notebooks is of exulted sorrow.

Hunger: A Memoir of My Body by Roxane Gay

Just as our surroundings define, temper, enliven and revise us, our bodies must either resist or surrender. Roxane Gay’s Hunger: A Memoir of My Body, aims this concept further inward to speak of how our bodies cage and free us. Though Gay insists that “(t)he story of my body is not a story of survival,” The Guardian calls Hunger “a memoir of suffering and survival” that “subtly questions not just how we judge ‘fat,’ but how we dare to judge at all.”

JC: Gay shows how we relate to the body as home, and the fat-shamed body as a shameful home. She describes her reaction to being gang-raped at twelve: “I ate and ate and ate in the hopes that if I made myself big, my body would be safe. I buried the girl I was because she ran into all kinds of trouble. I tried to erase every memory of her, but she is still there, somewhere … I was trapped in my body, one that I barely recognized or understood, but at least I was safe.” How would you define the politics of Hunger?

AF: “My story is mine,” Roxane Gay writes, adding that in being shared, her story joins “a collective testimony of people who have painful stories … I don’t want to change who I am. I want to change how I look. On my better days … I want to change how this world responds to how I look because intellectually I know my body is not the real problem. On bad days, though, I forget to separate my personality, the heart of who I am, from my body.”

The 300 pages of Hunger enact this conundrum, and one need only gaze at the full-length author portrait (rather than a usual headshot) included in a 2014 New York Times Magazine feature, to see in Gay’s face the toll it has taken and the strength, wit, skepticism, and paradoxical grace that her literary practice and presence have given her. I think the politics here boil down to the crucial role of storytelling in sharing the burden of carrying and taking to task “the cruelties of the world.” Gay’s evocation of the indignities of “super morbid obesity,” her avoidance of spaces, like seat rests in airplanes, at which her presence won’t be welcome, makes it possible that the next time her slenderer readers cross paths with a fat person, they’ll see the self that might once have stayed hidden from them.

Kill Class, poems by Nomi Stone

For two years, anthropologist and poet Nomi Stone embedded with U.S. military personnel in a simulated Iraqi war zone in North Carolina, spending her nights in a motel room. From inside their focus on war games and war, the poems in Kill Class examine the definition of body and self as it shifts among landscapes, identities, roles, and functions.

JC: She writes, “I am in a war. No, I am in a game of war. No, I am in a painting.”

She gives a sense of the surreal, the unreal, and how disorienting it is to “play” at war, to be at war. It seems she continues to try to stay grounded in herself. Is that possible in her circumstances?

AF: In the title poem alone Stone is assigned the role of Gypsy, fighter, grieving mother, reporter, traitor, spy, and rabbit killer, but she also resists those imposed identities by naming herself as poet, student, and anthropologist, while explaining to her reader, “I try to make small talk because other talk brings me out / you have to stay in.”

Although ostensibly Stone is guiding her readers through the rules of war games here—that in order to survive or even only to succeed in them, you must lie low—what she’s really talking about is that need to rescue and hoard her self, a task made always more difficult by some of the trainees calling her Sweetheart. Role-playing or not, all women everywhere deal with that, so back in “Motel Six After the War Game,” Stone is able to fold herself “into the smoky flowered coverlet,” and keep “the world above water” before she falls asleep. After first reading Kill Class, I remembered this scene as appearing again and again, but now I find it just once. It’s indelible. It recurs in readers’ minds even though it doesn’t on the page.

A Manual for Cleaning Women, selected stories by Lucia Berlin

“Never work for friends. Sooner or later they resent you because you know so much about them,” warns the speaker of Berlin’s title story here. The thing I love about these stories is that even as they map out the intersections between the laundromats, kitchens, cafes, and automobiles—and the women who make their living and/or their lives in them—the work is not fraught, is never bothered.

JC: A character in her story “Let Me See You Smile” has “a compassionate curiosity about everyone.” Would you say that’s what distinguishes Berlin’s writing?

AF: Yes, and taking the idea of “compassionate curiosity” further I’d add that Berlin refrains as if on the strictest of principles from judging her characters and even from applying questions of rightness and wrongness to their actions. I wonder if this was a personal attribute of hers and a foundation by which she lived her life, or a choice she upheld as a writer of necessarily (because aren’t we all?) flawed characters. Whatever the answer, you can see Berlin’s reluctance to hold her characters accountable for their misteps and transgressions in these lines from “Toda Luna, Todo Año,” when after a fisherman disappears at sea, “no one had said anything; at first Eloise didn’t notice that Flaco hadn’t surfaced, didn’t sense any fear until it was at least an hour after he should have been sighted. Even as the sun went down…César finally told Madaleno to head for shore.” I’ve noticed too in Berlin’s stories that a respite from goings-on often involves an embrace: between tourist and cook, upper crust student and Samaritan teacher, sober and alcoholic sister. These embraces go nowhere; they’re not meant to remark on, question, or put a stop to what’s happening. They’re just two people forming a momentary entity amid large and small calamity. Too, hugs are always made of compassionate curiosity, don’t you think?

JC: Indeed.

The Country Life, a novel by Rachel Cusk

Rachel Cusk’s comedic The Country Life opens with its heroine, Stella Benson, clearing all evidence of her existence from the tiny London flat owned by her parents, to whom she leaves a brisk letter explaining she’ll never see them again, then whisks her by train to an au pair position at a country estate whose entryway is flanked by giant stone pineapples. There she meets her employer, Pamela, whose greeting makes Stella feel “like a cross-section in a biological diagram.”

JC: In search of a home where she can “exist in a state of no complexity whatever,” Stella finds herself in a chaotic place. “It seemed incredible that so much could have gone wrong in so short a time,” Cusk writes. How does Cusk use details about challenges of the shift to “country life” to define Stella as a character?

AF: On her first morning in the countryside, Stella wakes to a darkness darker than in town. Soon she learns that country houses are shadowy and mysterious, too. Doors fail to open. Passageways materialize only to double back on themselves and take her back where she’s no longer sure she began, making it “impossible to get a sense of both sides.” It’s the same with people; her only friend in town turns out to be a “creature” of all but indeterminate species. Observing these puzzles, Stella persists in being matter of fact, as if an upright arrangement of words and sentences might form a wall between her and the things that upend her, including her own upendedness. Learning to drive, she feels “a curious mixture of the drunken excitement of achievement combined with the more sober consciousness of how fragile my control of the situation really was.” And on discovering at last that much of her confusion results from a frailer mental health then she, the reader, and perhaps Cusk herself had earlier imagined, Stella finds “something purifying” in her disarray, “if one can forget that it will inevitably lead at some point to the most brutal contact with the solid ground of reality.”

As for my own state of mind on once again reading A Country Life, first published in 1997, it’s worth speculating that the filtering out of setting as a culprit in Stella’s disarray marks a step in Cusk’s more recent move to autofiction.

JC: Good point!