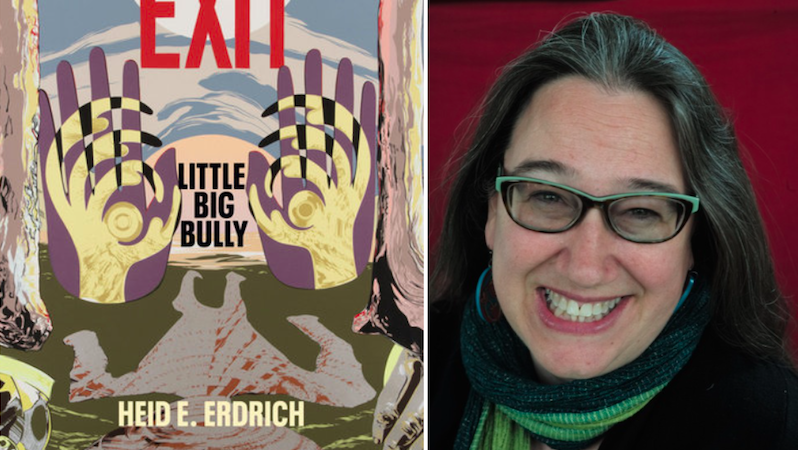

Heid E. Erdrich’s new collection, Little Big Bully, has just been published. She shares five books about survival.

Brother Bullet by Cassandra López

In addressing many poems to “Bullet,” the poet names her brother’s murderer, although the case remains unsolved. López quietly examines the details of the shooting, the police arriving, the hospitalization, the body after, and a year in survival mode. There’s no moment she claims to be a “survivor,” even in the fourth year toward the end of the book. This is a blessed relief and real as it gets. Still, we get a clear picture of ongoing survival in moments with her brother’s children and, most especially, López’s meditation on the desert and sea the two Cahuilla/ Luiseño siblings shared.

Jane Ciabattari: “After Bullet night / I promised to never turn away from the rib of the left behind, / the long scope of loss,” López writes. Beginning with the poem “Where Bullet Breaks: San Bernardino 2010” and ending with “Eclipse: Albuquerque 2012,” this collection takes us through the shattering experience of a loved one’s death by murder into a “new language,” as López puts it. You mention the meditation on the desert and sea she shared with her brother. Are there lines that particularly speak to you?

Heid Erdrich: There are so many lovely moments and I am so touched that López shares that intimacy between siblings, between loved ones. When we lose someone, it’s those tiny moments of memory that we try to retain, and sharing them helps. When I wrote the above, I was thinking of these lines in the final section of the book; “Did you see the thread / of desert, the way it steals the moon from the night?” from the poem “Sometimes” and, in “What Remains,” the description of childhood times at the ocean with the brother she mourns: “Following your path, / I shivered and side-stepped a speared stingray inking / sand, blooms of jellyfish. I searched /for your thin sunned brown back—but only saw the Sea / of Cortez. You are ash, chemicals compounded. You hide in / my glass pendant, sparkle green and blue, glint gold—transformed / Five pounds of specks remain. Shouldn’t there be more?”

Altar for Broken Things by Deborah Miranda

The “Indigenous elements/Story, Dance, and Song” allow the women in Miranda’s poems to look on destruction and yet worship creation. It’s her way with song that carries me from terrible moments in the past to present moments of peace. These are poems of exile and return that show us all a way back from brokenness.

JC: “Bees still pollinate the poisoned world,” Miranda writes. In what ways do her poems speak to our current toxic moment?

HE: Rather than attempting to convince anyone of what might happen to our world in terms of climate collapse, Miranda simply presents facts within her lines. It’s a poisoned world, not a world endangered by pollution. We should have been saying the damage is done all along, as Miranda does. Giving everyone a sense that the future is threatened, as much journalism does, gave the kind of people who don’t believe science that terrible gift of disbelief. If the destruction is coming, it’s not here, right? If there’s a future where we meet some kind of invisible line, after which is apocalypse, it’s still imaginary and some people can debate it or we think we still have time. We don’t have time. Now is the only way we can address what has already happened and survive it.

Catrachos by Roy G. Guzmán

These poems witness, among other things, the tremendous loving work of women, the work that is a path to survival for immigrant families. The love these women instill in a child, the loves they left behind, and the desire they understand, as well as the price for desire in a country rich with hate—all of these move Guzmán’s poems to create a distinct arc in the shape of lives lived in search of asylum.

JC: In this collection named for the enduring people of Honduras, Guzmán writes of a dinosaur named “Queerodactyl”:

After they locate and excavate your wing-fossils,

perseverance might be the trait you’re known for.

How swiftly you sloped downwards to pick up

the carcasses floating just above the bloodstained

surface of your old neighborhood. In the laboratory,

the paleontologists will use radiometric dating

to zoom into what bequeathed you that agency to fly.

This one might have outlasted all the others,

they’ll say. Might have even seen each one disappear

behind a bolt of fire blasted from who knows where.

How do they use humor to tell this story of survival?

HE: This is an interesting thing about Guzmán, they touch lightly with humor through inventiveness. They allow imagination to lift from horrific circumstances. It feels organic, part of Guzmán’s voice, but it is all so artful as well. I am so looking forward to Roy’s development of the quirky eye of this first book—the playfulness is power!

Upend by Claire Meuschke

These poems worry away at the violence and mystery of her grandparents’ generation composed of Chinese immigrants and the women, sometimes Native, they marry. Mail order brides and missing women haunt Meuschke’s fragmented and disturbed search for whatever story survives in the notes, transcripts, color swatches and Lost and Found listings she includes to understand her own survival.

JC: Meuschke writes of her Alaska native great grandmother, who was listed as “Unknown: Indian” on the birth certificate of her grandfather Hong On, and of Hong On, whose 1912 immigration trial on Angel Island during the Chinese Exclusion Act inspires these poems. “In 1850 California / the state funded bullets for volunteer killers / the price for an Indian scalp / was at least 10 dollars,” she writes. In lines like these she evokes a lost history. How do acts of retrieval like these poems contribute to survival?

HE: We who have been forgotten, erased, made invisible in history need to take our voices and sometimes that means reclaiming our ancestors, especially the women whose lives were so blithely recorded in the generic. This happened in my/our own family history, so this aspect of Meuschke’s work really caught my attention. We try to speak the names of our ancestors in order to thank them for our survival—and if we can’t, how are we to carry them forward and survive as they did?

Sula by Toni Morrison

Sula is on my list of classics—a slim book that has haunted me since the last years of my childhood. Beginning with tender girlhood moments, Morrison shows the vulnerability and creativity that young Black women must leave behind to survive. It was this book that showed me that your whole life, each exquisite moment, each brutal assault, each desperate act of survival, and each of your deepest and loneliest thoughts could lead you home.

JC: I was in graduate school when I first read Toni Morrison’s story of Nel and Sula, girlhood best friends in Medallion, Ohio, whose lives follow separate paths; it was the first Morrison novel I’d read, and it blew open doors I’d perceived as locked for women who wanted to write. “Hannah, Nel, Eva, Sula were points of a cross—each one a choice for characters bound by gender and race,” Morrison writes of Sula. “The only possible triumph was that of the imagination.” Her own imagination triumphed, and she was able meet her goal: “I wanted to redirect, reinvent the political, cultural, and artistic judgments saved for African American writers.” How did Morrison inspire you during your work on Little Big Bully?

HE: You know, I am not sure I thought of Morrison in working on Little Big Bully, except in the way I hold her work as grounding for women whose histories include abuse and oppression—which is most women, really. When I began to read Black women authors, Native American women writers, and writers who wrote from their own endurance, I began to believe that we could all overcome harm and thrive. It’s the same with this new book of mine—look at it, name it, be clear-eyed in how you make it past harm to protect yourself, to get distance and never fall for the bully again. We can stop doing the bully’s bidding and especially stop telling their stories. When they don’t get a reaction, they hate it and eventually they weaken or just stop. It’s like a miracle—one day it’s just gone, to paraphrase a bully we all know.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·