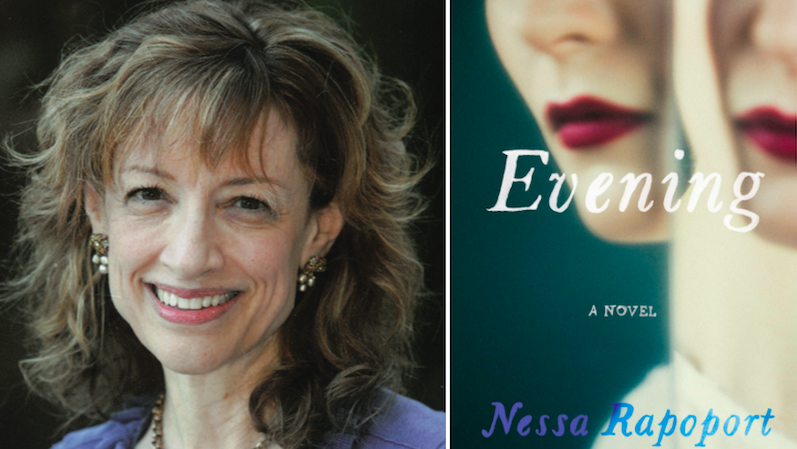

Nessa Rapoport’s novel Evening is published this month. She shares five books about sisters and secrets.

The Greengage Summer by Rumer Godden (1958)

Five precocious British siblings come to spend a summer at a sleepy hotel in France, during which their relationship with one another and with the adult world is inflected by a mystery and a secret. For the two sisters at the center of the story—Joss, the eldest, at sixteen, and Cecil, the narrator—the three years between them become consequential in this delicate drama of innocence transformed.

Jane Ciabattari: “The orchard seemed to us immense, and perhaps it was, for there were seven alleys of greengage trees alone; between them, even in that blazing summer, dew lay all day in the long grass. The trees were old, twisted, covered with lichen and moss, but I shall never forget the fruit.” Godden’s narrator, Cecil, 13, captures this hot August in France so well, and also the rivalry she feels toward her older sister, whose blossoming into womanhood that summer draws male attention. How would you describe the balance Godden sets up between these two—more loyalty than betrayal?

Nessa Rapoport: Far more loyalty than betrayal, although what Godden does so elegantly in a book I’ve reread often is to portray the complexity of feeling between these two sisters. I am the eldest of four sisters, and so, it emerges, was Jon Godden, a year older than Rumer, each a writer; they also wrote two memoirs together and a collection of stories. Emotionally, Rumer knew whereof she spoke—the shuttle of devotion, competition, and flares of near-hatred that can elevate and afflict sisters.

The Moonflower Vine by Jetta Carleton (1962)

Four spirited sisters in rural America, a secret that unknowingly conditions their lives, and an ending that made me cry.

JC: When the sisters visit their family farm in Missouri near Kansas City, it’s the time of moonflowers bloom. “The flowers were so lovely and they lasted so short a time,” Carleton writes. “It was…something you looked forward to all year, then it came, and you enjoyed it so much, and then it was over, in no time.” Why is it so important to keep secrets in their hometown? Because “respectability” is so important?

NR: Secrets are intrinsic to love—those one holds close, those one discloses. Among the reasons I chose to live in New York City is the anonymity a big city confers. The small town in this novel—in a very different America—brims with caring, but also meddling. The evanescence of the moonflowers’ blooming stands in for the advance and retreat of understanding among sisters, with synapses and silences that feel necessary not only toward townspeople but within themselves. This family exemplifies flawed love, love interrupted, love undone—always undergirded by an earned compassion. The Moonflower Vine’s through line is that we strive, fail, and yet, if we’re blessed, continue to amplify our understanding enough to forgive.

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson (1980)

Decades before the quiet beauty of Gilead, Home, and Lila, Robinson published Housekeeping, a startling novel about two sisters, Ruth and Lucille, in a family jangled by abrupt death and eccentric guardians. As children, the sisters are a harbor for each other in their isolation from small-town dailiness—but one goes on to accept and embrace transience, while the other needs an orderly, sedate life.

JC: I’ll never forget first reading Housekeeping. The image of that train crossing over the lake in Fingerbone, Idaho, and then the accident, and mysteries of what’s beneath the surface. The novel is haunting and lyrical—musical, even—and tragic. Two sisters, orphaned, raised by a maverick aunt Ruthie after their mother dies, yet so different.

“Families will not be broken,” Robinson writes. “Curse and expel them, send their children wandering, drown them in floods and fires, and old women will make songs of all these sorrows and sit on the porch and sing them on mild evenings.”

How would you describe the ties between the sisters?

NR: Sisters are uniquely bound to one another, inventing a vocabulary and culture that no one else can quite share. They also, of necessity, polarize each other. Trauma and tragedy draw these sisters close, but also compel differing defenses—and choices. These sisters can no longer protect one another, or they feel as if they can’t. Their ties may be as powerful, but they believe that their paths no longer align. It’s that conviction, rather than their choices, that necessitates the close of this remarkable book.

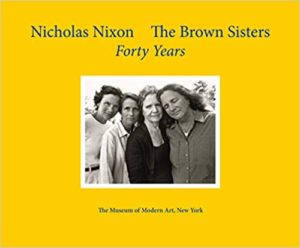

The Brown Sisters: Forty Years by Nicholas Nixon (2014)

Nicholas Nixon photographed his wife and her three sisters once a year for 40 years. My sisters and I are about the Brown sisters’ age; I watch these parallel four sisters change from the unlined brightness of youth to a middle-age of experience, weariness, and wisdom. Riveting, tender, elegiac, and still shocking—as if all of our own lives were passing before us in an instant. The camera exposes their wonderful faces but leaves their dignity—and their secrets—intact.

JC: When did you first encounter this revelatory book?

NR: I read a review of the exhibit and then had to see it at the Museum of Modern Art. I have always been riveted by the contrast—in the same face—between the beauty of youth and the marks of aging and sometimes ruin, fascinated by the young-older faces of Marianne Ihlen (“So Long, Marianne”), Julie Christie, Caroline Blackwood, Joni Mitchell, and M.F.K. Fisher, among many others I’ve scrutinized online. Our faces are a palimpsest of all we’ve undergone. What are the Brown sisters thinking as they submit to this annual ritual? I meet their gaze, longing to know.

Testament of Friendship by Vera Brittain (1940)

Chosen sisters, writers, and activists, Vera Brittain and her soul-friend, Winifred Holtby, met at Oxford after the Great War had slaughtered a generation of men, including Brittain’s brother and fiancé. Crafting an independent life that supported their ambition, they were inseparable. When Brittain married, it was on condition that her new household include Holtby, and Holtby helped to raise Brittain’s two children. Holtby’s brilliant life was curtailed at 37 by an incurable illness she kept secret.

The heroine of Evening is writing—and avoiding—her PhD on Holtby, who published seven novels, poetry, essays, and journalism, and was an outspoken champion of feminism, pacifism, and racial justice. Holtby completed what is considered her finest novel, South Riding, three weeks before her death.

JC: In what ways did Holtby and Testament of Friendship inspire you in your work on Evening?

NR: Growing up in Canada, whose Commonwealth flag was the Union Jack until 1967 and whose national anthem, when I was a child, was still “God Save the Queen,” I read British fiction—I was one of those children who read novels compulsively as I walked down the stairs—and studied British history. Like my narrator, Eve, I am never unaware of the vagaries of fame. We strive, in our tenure on earth, to pour forth the gifts we were given. But any student of literature or history knows that even those who attain global luster in their day will likely be forgotten, not only in one generation but in a decade. Sobering.

Still, love endures. My vision of an afterlife is that love, like energy, does not die but transmutes into a different form. Vera Brittain’s and Winnifred Holtby’s love was exceptional, the apotheosis of friendship between women, a fierce devotion that was a balm against a tragic past and, for Brittain, decades of a future without her dearest friend.

I was introduced to Brittain’s Testaments by a very close British friend who knew their story firsthand. And I’m perennially intrigued by this generation of British women writers. In the aftermath of the War to End All Wars, they left the confinement of their provincial homes and roles to make their own way, unlike their mothers and grandmothers. Coincidentally, my heroine is as fascinated as I am.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·