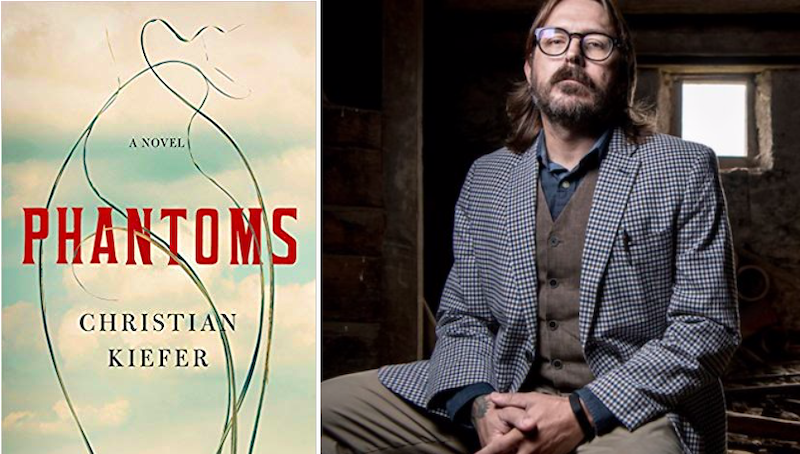

Christian Kiefer’s Phantoms is published this month. He shares five books about mothers who are also human beings, noting, “Phantoms is about race and history, but it is also about motherhood and what a mother will do to protect herself, her children, and her family. For this list I’ve tried to select five books that address the idea of motherhood from different points of view. I would also like to acknowledge here that it is perhaps problematic for a male writer to select books about mothers. All I can claim is that these are books which have been, and continue to be, important to me. Please forgive me if you feel I have overstepped.”

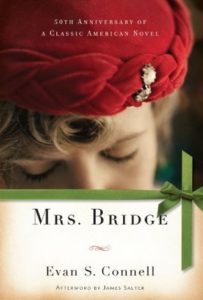

Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell

What Connell does in this account of suburban malaise is simply astonishing. It is a book where nothing really happens and also one which contains the whole of human experience. Fettered in ways she is not even able to acknowledge; Connell’s India Bridge lives her life in a kind of snow globe of privilege but time marches on even if her own understanding of the world around her does not. The contrast is fascinating and beautiful.

Jane Ciabattari: Mrs. Bridge, Connell’s first novel, published in 1959, was a pioneering novel-in-flash—117 illuminating glimpses that create a whole. It was one of the first novels I ever read that was set in Kansas City, a couple of hours from where I was born (I’m a fifth generation Kansan, descended from an abolitionist who was a chaplain for a black regiment in the Union Army). I recognized the mothers of my home town in India Bridge—in her sad state of being locked into a homemaker’s role, fearful of judgment, dependent upon her husband, unable to express her feelings. In one indelible scene, a monstrous tornado bears down upon the country club while they are having dinner there. Mr. Bridge refuses to leave his steak, she refuses to leave him. “In darkness and silence she waited, uncertain whether the munching noise was made by her husband or the storm.” Her feelings about her children are poignant, as she struggles to turn them into polite citizens and watches them rebel. Her son Douglas, Connell writes, like the tower of garbage he builds in the yard, “seemed to be growing away from her reach.” What are your favorite moments?

Christian Kiefer: I’ve come to understand that one of the aspects of art—in all its forms—that I love the most is subtlety and Connell’s is perhaps the most subtle novel I’ve ever read. There’s so much creeping unrest but it never explodes and in fact the ending scene—with Mrs. Bridge caught midway in/out of her own garage, unable to get out of the car—is the closest we ever come to rupture. It’s like a slowly bubbling pot, the lid rattling, but never quite spilling over. Marvelous and, of course, very sad, because one of the points of the novel is that Mrs. Bridge doesn’t understand herself well enough to understand why she remains unfulfilled. She has attained everything that our society tells her she needs and yet…and yet…and yet…

Florida by Lauren Groff

Groff is among my very favorite contemporary writers, one whose sentence-level writing I find utterly enthralling. Florida, her second collection, includes several stories about mothers pushed into situations that test the edges of the maternal. Groff’s characters are always problematic in the most human of ways and in the dynamic between her mothers and children we find truths about a wider world on the edge of collapse.

JC: Groff creates such drama from domestic situations. The mother in “The Midnight Zone” is vacationing with her two sons in a remote cabin when she falls while changing a light bulb and ends up with a concussion. Suddenly the roles are reversed. “I had begun shaking very hard, which my children, sudden gentlemen, didn’t mention.” Then we have the mother who leaves her family at home and takes off for a walk to get a grip. Groff opens with the line, “I have somehow become a woman who yells.” How do you think she achieves that intimate emotional tone?

CK: Groff is among our greatest contemporary writers and is one writer for whom I drop everything when something new appears. Her control of language, of sentences, of syntax, is matched only by her genius. The domesticity in the stories in Florida is often tinged with menace and you’re right to point out “The Midnight Zone” as a prime example of this. Her particular genius (and yes I’m using genius twice in this paragraph and I mean it both times) is writing about very very specific characters and making them so fully alive that they become, in a sense, universal—which is to say that a great many of us parents have had the “I have somehow become a woman who yells” moment—or moments. It’s those seemingly cast away lines that really break me when I read her work. There’s a mirror of that yelling line at the very end of the story too: “My husband filled the door. He is a man born to fill doors.” As if he is, by his very being, his very size, a more capable human being somehow—and that’s a thin line of guilt that runs straight through the story. We’re all just trying to do our best.

Where Reasons End by Yiyun Li

A book so stunning that I do not even know what to say about it. This is novel that should not work—a kind of longform discussion between a mother and her dead teenaged son (a suicide). The discussion that ensues is without location or setting—or rather the only setting allowed is the text itself—and it is deftly structureless, moving from topic to topic, idea to idea, as the speakers see fit. And yet this structureless quality is, of course, only a further mark of Li’s genius for one can sense, all the while, just how carefully is laid each letter, each piece of punctuation. This is not poetic so much as it is poetry itself.

JC: What makes this novel about a sixteen-year-old’s suicide so profound is the tone, traffic yet playful, and the language. Can you give some examples of her structural approach?

CK: I don’t even know what to say about this novel. It’s so brilliant that it feels like something you just can’t really talk about. I will say that this kind of novel shouldn’t work and I mean that in the way that the film My Dinner with Andre shouldn’t work—it’s just people talking and nothing else. There’s really no development, no setting (ostentatiously setting-less, actually), just two basically disembodied voices in conversation. And yet the whole of the book is fraught with emotion even in its most banal moments. (And I mean that in the way that someone like Henry James or Mavis Gallant or Shirley Hazzard can run that line of profound banality.) Li has said that she wrote this book very quickly and yet it feels incredibly meticulous, every single word carefully placed like a jewel, every one of which is there to break your heart.

Mrs. Fletcher by Tom Perrotta

As a reader I do not much gravitate toward comedic fiction but Perrotta’s novel is an absolute riot. The titular Eve Fletcher is a woman suddenly occupying an empty nest and confronting, among other issues, her own sexual loneliness. Meanwhile, her college aged son, Brendan, is behaving badly in all possible clichéd ways. The mix is wonderfully funny and fucked up.

JC: Right. Brendan is “a big, friendly, fun-loving bro, a dude you’d totally want on your team or in your frat” and after she drops him off at college his mother, Mrs. Fletcher, leaps back into the world of dating and internet porn. Do you find Perrotta’s depiction of this mother-teenage son relationship authentic?

CK: I do indeed find those relationships to be authentic although I’m lucky in that my own kids are (so far) not as bro-like as Brendan. He’s in college largely to hang out and party and his mother is, in the meanwhile, trying to understand what it means to be single again, unfettered by the constant presence of her only child. She’s lonely, he’s confused, and their two stories parallel and occasional crash into each other. My oldest is 24 and he’s a great guy but of course you don’t know, as a parent, what they’re doing once they’re out on their own. You hope you’ve done what you can to make them the kind of a person you want them to be but really they’re claiming their own lives at that point.

Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward

Jesmyn Ward is a true master of both novel and memoir and this, her most recent book, is so filled with heat and sweat that, as an object, the book seems to physically emit a kind of sickly miasma. Part family drama, part road trip, Sing, Unburied, Sing follows Leonie and her son Jojo on a road trip to Parchman Farm. Their journey is peopled not only with living and breathing souls but with the shades of the dead, ghosts that sidle up alongside to tell their part of the family’s story.

JC: Jojo’s qualities of observation are remarkable; he renders his troubled, neglectful, addicted mother in sharp detail. He’s being raised by her parents, not by Leonie: “She ain’t Mam. She ain’t Pop. She ain’t never healed nothing or grown nothing in her life, and she don’t know.” Yet he seems so forgiving. Why do you think that is possible, despite the harshness between them?

CK: Jojo is one of the great characters in literature, as far as I’m concerned, and in fact the whole book is remarkable. I was reminded of his forgiving qualities—his inherent goodness—when I watched Cuarón’s film Roma. In that film Cleo is similarly forgiving and caring, despite the fact that she’s only a member of the family for whom she works when it is convenient to them. Jojo’s in a similar state in his family—his mother’s son when it’s convenient to his mother, otherwise a kind of nuisance. And yet there is care and love in that family. Jojo sees beyond the world, too, which offers a larger perspective than any other character in the book is capable of as the narratives he is told—and which he absorbs—literally come to sit next to him. Perhaps it’s largely this connection to the stories around him that allows him to connect.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·