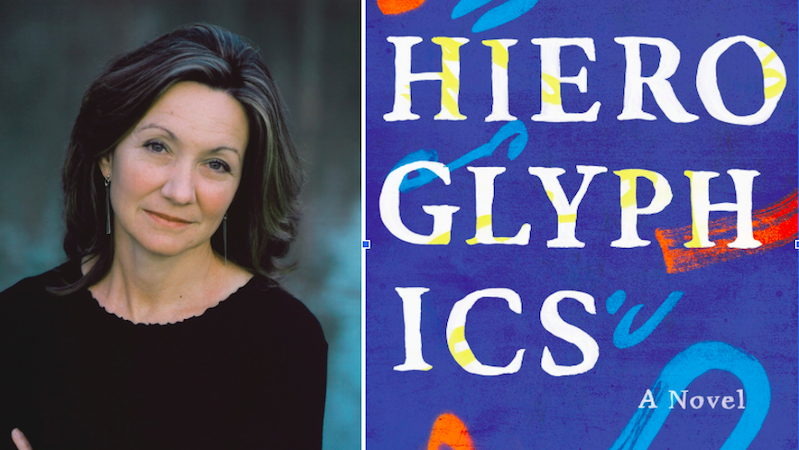

Jill McCorkle’s new novel Hieroglyphics is published this month. She shares five books in her life, noting, “I have always been drawn to those works that rely heavily on memory as well as how a community might feed memories in different ways with emphasis on those events early in life that become touchstones for the whole.”

Our Town by Thornton Wilder

Our Town is probably the first work that really grabbed me emotionally and never let go. From junior high school on it continues to hold that power. In a similar way, The Glass Menagerie is a touchstone—a “memory play”—but choosing between the two plays (a hard choice) I will choose Wilder for the list.

Jane Ciabattari: I’ll never forget seeing a production of Our Town at Lincoln Center, with Spalding Gray as the Stage Manager. (Here’s his opening monologue.) The Pulitzer Prize-winning play covers one day, May 7, 1901, in Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire, beginning just before dawn. In the course of that day, George and Emily fall in love, marry, and reach a tragic end. I’ve always been struck by Emily’s reaction after being granted last moments on earth. “It goes so fast. We don’t have time to look at one another. O, Earth, you’re too wonderful for anyone to realize you.” Do you have passages that linger, and influence your own work?

Jill McCorkle: Oh yes. And I always hear the voice of Hal Holbrook, who played the part in a televised version in 1977. I love the part you just quoted and I also immediately think of the scene where George’s sister, Rebecca, is telling about a letter someone received and the way it was addressed, moving from the traditional Jane Crofut, Grover’s Corners to “…the Solar System; the Universe; the Mind of God,” and then she says “And the postman brought it just the same.” In fact, I often think that line when I drop something in the mailbox, still amazed that a letter can find its way through miles and chaos to the hand of a specific individual. My Dad worked for the post office for many years which might make that one even more endearing to me, but I feel it also makes the point that Wilder stresses throughout—the recognition and respect that every individual life against the universal backdrop deserves, and the specific details that separate that life from all others. I like when Emily asks her mother if she’s pretty and her mother responds: “pretty enough for all normal purposes.” So much is happening in that scene: a mother, long past her own youthful dreams, who might be a little fearful that her daughter could reach too high and be disappointed in life, and a daughter still very much filled with romantic dreams and needing/wanting encouragement. I also am inspired by the way Wilder reveals the deaths of various characters right up front and then immediately resurrects them for the scene. The future knowledge leaves us hyper aware of all that will be grieved, which of course is beautifully depicted in the final scene when Emily says, “they don’t understand, do they?”

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers

From McCullers, I learned the power of a community portrait and the way intersecting lives have an impact on the shaping and memories of others. (I might also name Winesburg, Ohio for very similar reasons but again, will choose for the sake of the list.)

JC: This first novel was published when Carson McCullers was twenty-three. Here’s how she describes the small community in her first chapter, about Singer and Antonapoulos, two mutes who live together for ten years:

The town was in the middle of the deep South. The summers were long and the months of winter cold were very few. Nearly always the sky was a glassy, brilliant azure and the sun burned down riotously bright. Then the light, chill rains of November would come, and perhaps later there would be frost and some short months of cold. The winters were changeable, but the summers always were burning hot. The town was a fairly large one. On the main street there were several blocks of two- and three-story shops and business offices. But the largest buildings in the town were the factories, which employed a large percentage of the population. These cotton mills were big and flourishing and most of the workers in the town were poor. Often in the faces along the streets there was the desperate look of hunger and of loneliness.

Which of McCullers’s characters has most lingered with you over the years since you first read The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter? (And I could ask the same of Sherwood Anderson!)

JM: McCullers was so gifted in portraying adolescence with all the exuberant fantasies alongside the painful realizations of life’s limitations. Mick (like Frankie Addams in Member of the Wedding) is stuck between the two worlds, clinging to her dreams of a life fueled by music and an education and foreign travel, and the sad and practical needs of her family that will hold her in place. She and Mr. Singer are both aware of the hunger of loneliness and both sensitive to the losses of others; in fact, her relationship with him seems a kind of education in loneliness and an acknowledgment of how much we often don’t know about the people in our lives. Singer is like a mirror, reflecting whatever someone needs, his silence absorbing their woes without anyone really venturing into his. His death, then, is a wakeup call to those who have taken his presence for granted. There is a great description that describes his hands moving and shaping words when thinking of the loss of his friend, “like a man caught talking aloud to himself” and he describes how his hands would not “let him rest.” The movement of his hands reminds me of a favorite Winesburg Character, the teacher Wing Biddlebaum, whose life is tragically stolen from him by false accusation. I also think of Alice Hindman, who holds onto a dream too long and winds up alone, and Dr. Reefy (a particular favorite), who like Mr. Singer seems to rescue others and serve as a magnet for their grief—I love the image of all the little notes in his pockets—the paper pills holding his thoughts and ideas within a day.

The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter

Favorites being “The Jilting of Granny Weatherall” and the early Miranda stories (“The Grave,” “The Circus”) dealing with childhood memories. I learned so much in the way she beautifully represents extreme ages, from early childhood to death.

JC: This collection of nineteen stories (of the twenty-seven Porter wrote) won the Pulitzer and National Book Award. It’s back on the radar now because it includes “Pale Horse, Pale Rider,” Porter’s novella set during the 1918 flu pandemic (she was a flu survivor). It’s one of Porter’s Miranda stories, and one of the stories in which she confronts death, who appears to Miranda as a stranger in a dream who regards her without expression. Granny Weatherall stands out for her rebelliousness at eighty (“So good and dutiful, that I’d like to spank her,” she muses about her daughter. “She saw herself spanking Cornelia and making a fine job of it.”) She sinks into her death in the final passages of that story:

Her heart sank down and down, there was no bottom to death, she couldn’t come to the end of it. The blue light from [the] lampshade drew into a tiny point in the centre of her brain, it flickered and winked like an eye, quietly it fluttered and dwindled. Granny lay curled down within herself, amazed and watchful, staring at the point of light that was herself; her body was now only a deeper mass of shadow in an endless darkness and this darkness would curl around the light and swallow it up.

What does Porter’s work have to tell us in this pandemic era?

JM: I think that Porter’s work is often about putting emotions in perspective—or i should say trying to. I have often compared the example of Miranda, the grown woman, in “Pale Horse, Pale Rider” and Miranda, the child, in “The Circus,” both overwhelmed by fear and the shadow of the unknown. Fear is fear and I admire the respect that Porter gave to the emotions of children, those early powerful moments that they only come to understand later. Over my desk, for at least twenty years, I have kept the Kierkegaard quote: “Life must be lived forward but it can only be understood backward.” As a writer, I am endlessly fascinated by characters seeking that understanding while also muddling through the unknown. Certainly, Porter’s characters are often doing just that—reaching back with discovered awareness and understanding—but also having to confront all that is out of their control. I think that as a survivor, her work brings an awareness of the fragility of life. At the end of “Pale Horse, Pale Rider,” she is caught between the grief of a loved one’s death and the reassurance that she will live and with that, an outpouring of what she will do as a result—“visit the escaped ones…tell them how lucky they are, and how lucky I am to still have them.”

A Death in the Family by James Agee

I am inspired by the defining moment in childhood that shapes the whole life and here I am especially admiring of Agee’s ambitious use of the older voice integrated with the child’s sensibility.

JC: Agee’s autobiographical novel, which won the 1955 Pulitzer, covers the first six and a half years of Baby Rufus’s life, before the death of his father in the summer of 1915 in Knoxville. Agee uses multiple points of view the tell the story, and in particular captures the Baby Rufus’s view in passages like that describing his mother singing “Swing Low, Sweet Cherryut.” Agee also gives a near eternal perspective to lines like this: “One by one, million by million, in the prescience of dawn, every leaf in that part of the world was moved.” Which perspective has most influenced you?

JM: I love Baby Rufus, but I am most inspired by that older, “eternal” perspective. Agee’s italicized sections seem to stand separate as a kind of meditation on early memories. I think often of Agee’s line in the opening: “in the time that I lived there so successfully disguised to myself as a child.” That opening describes so beautifully the sensation of innocence—the adults talking and then lifting him to the safety of his bed; I never see or read about a child being carried to bed that I don’t think of this opening. And then of course there is the revelation that these adults “will not ever tell me who I am.” The passage about darkness functions in a very similar way, capturing the sensibility of a child’s fears in the language of an adult who fully understands loneliness, moving seamlessly from child to father as he speculates on how to get back home: “You have a boy or a girl of your own and now and then you remember, and you know how they feel, and it’s almost the same as if you were you own self again…” Agee, in that section, provides a beautiful sense of time travel from child to parent and back to child—that original self.

So Long, See You Tomorrow by William Maxwell

Maxwell wrote so beautifully about memory and those moments that haunt us. His attention to the specifics of home and everyday life are incredibly moving and, like Wilder, secure a whole place and community in memory.

JC: Beginning with that Chapter One title, “A Pistol Shot,” Maxwell examines a murder in the 1920s fifty years later. It’s a structure we see continuously now, not so much when this was first published in two issues of The New Yorker in 1979. Even better, Maxwell’s second chapter explains why the narrator cares: 1.) The murderer was the father of someone he knew and 2.) he did something he was ashamed of afterward. How has this approach show up in your own work, in particular in your new novel Hieroglyphics, which reveals how memories of tragedies surface years, even decades after they occur?

JM: One of my characters says, “We are all haunted by something. Something we did or did not do.” Maxwell’s haunting of that moment when he pretends not to know the boy, is a sensation we all know, though likely one we don’t like to admit. It’s that moment that makes us shake our heads or sit up in bed—a regret, a missed opportunity, a moral failure. We think those moments will never leave us alone. Some fade, some even might disappear—the more childish ones—but the others—those that involve another person’s feelings and our own sense of a moral failure—linger and if we’re lucky, we learn something we can use. The effect of Maxwell’s beautiful novel is to send us to our most humble and honest places, which is what I hope to do with my characters, or I should say those characters who find resolution. For the sake of reality, they don’t always get there, but I like to at least jimmy the door and leave the reader (and possibly the character) aware of the threshold. I think that a character’s recognition and awareness of the fragility of life and the human soul is about as satisfying a resolution as is possible to find. It’s that backwards journey that enables us to find meaning, all those small, seemingly ordinary moments that define and shape us.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·