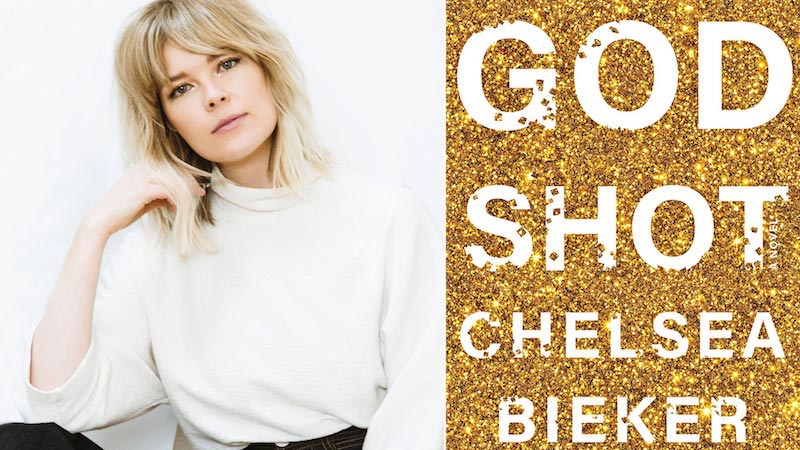

Chelsea Bieker’s Godshot is published this month. She shares five books about coming of age in the West.

The Girls of Corona Del Mar by Rufi Thorpe

This is a stunning and addictive portrait of a friendship between two girls spanning from elementary age to adulthood, beginning with their childhood growing up in southern California. Eventually we get to watch Mia and Lorrie Ann grapple with motherhood and all its complicated strains. I love the reach of this novel.

Jane Ciabattari: One of the strongest elements of this novel is the ways in which the “good girl”/”bad girl” dichotomy unravels over time. Do you find that unraveling realistic?

Chelsea Bieker: I do, in the sense that I don’t believe in life, or in fiction, that people are ever all one way, either good or bad. We each contain multitudes and the reveal of this in The Girls of Corona Del Mar is so expertly done, and gives both characters so much complexity. In painting any villain character, too, the idea of never underestimating the loneliness of the monster or the cunning of the innocent comes into play to create characters that are both human and interesting to read. It’s not interesting if characters behave just one way. Then they become too predictable. If they later disappoint or act in the expected way, it packs more of a punch because we first saw their complexity and potential for many outcomes.

White Oleander by Janet Fitch

This is my favorite novel, and feels like something of a Bible to me. I can’t think of any other novel that, for me, so perfectly captures Los Angeles and what it is like to be abandoned by your mother, the far spanning effects of this loss. The prose sparkles like poetry.

JC: Fitch is masterful at giving a natural backdrop to this story of a woman who murders her lover and ends up in jail, abandoning her daughter to foster homes. The opening lines are a perfect setup: “The Santa Anas blew in hot from the desert, shriveling the last of the spring grass into whiskers of pale straw. Only the oleanders thrived, their delicate poisonous blooms, their dagger green leaves.” And later, “the oleanders cooking down, the slight bitter edge of the toxin.” Although I’d seen oleanders on visits to Malibu, I hadn’t realized they were poisonous until reading this novel, and I never forgot it! What did you take from this continuous evocation of toxicity?

CB: The idea that something so beautiful can be deadly seems unfair, the way many things that are not good for us are so delicious, or certain toxic relationships can feel so addictive. I remember first learning of oleander’s poisonous nature as a child in California. My mother told me the story of a boy who skewered a hot dog with a white oleander branch and ate it and died and it created a fear in me of all flowers and their potential residues or toxins. I don’t know if that’s a true story but it made me question flora and fauna in a steadfast way ever since, so it was effective. In White Oleander the mother’s toxicity is widespread and unfurls again and again, through Astrid’s unpacking of memory.

In My Father’s Name by Mark Arax

I have long loved the way Arax writes of the Central Valley of California and coming of age the son of an Armenian immigrant father trying to make his way in a rich land of promise—and his father’s subsequent murder, which is at the core of this book. With fierce and unrelenting reportage, he manages to paint a stunning and layered portrait of all the gorgeous and gritty realities of Fresno, California.

JC: Arax compares Fresno to Chicago, as he discovers its layers of crime and corruption. But as a friend says to him, “This is not about solving a crime. It’s about solving a life.” What does Arax learn about Fresno that helps solve the crime, the life?

CB: To me, what this book does is both an interrogation and an homage. It’s a critical, steadfast look at the Central Valley, but also a love letter in many ways. To describe a place with such clarity and beauty and attention, however critical, evokes a kind of love. He also touches on something that I too have felt about the valley, that something about it, once you have lived there, feels inescapable. The place feels oddly both dead and alive, at odds with something innate in me, but still, I can long for a Fresno summer night, the way the heat feels on asphalt and the particular smog of blue sky fading overhead. It’s particular.

The Girls by Emma Cline

This novel explores the slow build and allure of joining a cult through the lens of a teenage girl in California, searching for identity. I love the exploration of a narrator grappling with her definition of feminism in this book: “I waited to be told what was good about me. I wondered later if this was why there were so many more women than men at the ranch. All that time I had spent readying myself, the articles that taught me life was really just a waiting room until someone noticed you—the boys had spent that time becoming themselves.”

JC: The Girls opens in the narrator Evie’s present—in a borrowed beach house—but the most vivid scenes are from her past, with her attachment to a Manson-like cult in 1969 in Petaluma, when she was fourteen. The grifter who runs the ranch is a musician, nobody special, but he’s adept at exploiting insecure teenage groupies, and sending them off to do his evil deeds. How does Cline’s use of language—her sentence fragments, her ultra-vivid descriptions—help build these scenes from the late 1960s?

CB: I think evoking any time period well is about specificity. Cline has a skill for describing things that are not only rooted in a time period but also rooted to Evie’s eye. We see things through her remembering them in technicolor—this time that has been so branded into her. It’s the story she will tell forever and you can feel that in the language, and the way these things are remembered.

Pretty Little Dirty by Amanda Boyden

My childhood best friend and I read our single jointly owned copy of this novel in desperate turns, stealing it from each other and fighting over it, and then talking about it for hours until the main characters, Celeste and Lisa became something of our alter egos, for better or worse. Our obsession with this book, admittedly led us into some strange circumstances, trying perhaps to replicate the reckless thrill the two friends share as they come of age first on the east coast, and later in the punk music scene of California, in a world of checked out parents and burgeoning sexuality, and older men, and drugs. We were nineteen going to community college in our central valley hometown and this dive into the insular and loving and jagged territory of young best friendship felt like an awakening, a permission.

JC: What’s your favorite scene or chapter from Pretty Little Dirty?

CB: What pulled me in and intoxicated me about this book was the way Lisa sees Celeste with such accuracy but also with such a true adolescent glorification. The point of telling is far off, she has the wisdom of time, and still, the truth of Celeste never shifts in its intensity. We feel also the deep love and admiration Lisa has for her, and at times we see its underside, which is a complicated jealousy. I think Boyden captures adolescence, a time when we are looking to others to learn how to be, and everyone provides a lesson to us, offers us something to take or leave, purely. We see that in Lisa’s assessment of Celeste, that particular attachment you can only have when you’re young with a friend, when you can spend every single day together, inhabit each other completely.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·