Perhaps because I was raised in the damp and crowded heart of Seattle, I have always loved the bone-dry, sparsely-peopled American West. From a child, I wished that I had been raised far from town under an endless sky. My godbrothers, who grew up on a cattle ranch in Montana, shot rifles and drove trucks at ten years old. They owned horses when I had a hamster. Most importantly, they ranged semi-feral across miles of coulees and dryland wheat fields, cultivating a strain of adulthood and consequentiality that I could not manufacture from the raw materials of a city.

When I finally packed my things and drove eastward on Interstate 90 to take a ranch job in the Madison Valley, I was searching for the landscape and work that had shaped those hard-handed godbrothers of mine.

I found it. For more than a decade, I have baled hay and calved heifers. I have managed ranches—been used both well and poorly by the millionaires who own too much of Montana. I have borne witness to the destruction of beloved places and noticed cracks in the shining Myth of the West.

But though I’ve made my living from this landscape and have chosen to remain, I still don’t know what it’s like to grow up out here—how it feels like to be sprouted in the gorgeous, unpitying soil of Montana or Wyoming. Instead, I get to read about it in books like the five I’ve excerpted below.

These fine, gripping stories—four memoirs, one novel—are united by through-lines of aridity, wind, and brutality. Read the following selections, and you will begin to glimpse our storied region through the sharp, unflinching eyes of its sons and daughters. Read the books, and you’ll see a whole lot more.

*

Hole in the Sky by William Kittredge

“The point here is abundance, an overwhelming property thronging with natural life, and what my family did with it. My grandfather wondered how such a place could best be used. My father tried to show him. That was probably my father’s main mistake, making any effort at all to live in his father’s life. But they were family, and my father saw that valley as possibility. Oscar Kittredge had been to school at the Oregon Agricultural College in Corvallis; he was an engineer, one of the new men, a visionary.

“He bought a cable drum Caterpillar RD-6 track layer fitted out with a bulldozer blade, which he used to start building a seventeen-mile diversion levee to carry the spring flood waters of Twenty Mile Creek north along the east side of the valley, to drain our swamplands. Seventeen miles. In those times such a project was considered insanely ambitious.

“My father was the joke of the country, but not for long.” (41)

Breaking Clean by Judy Blunt

“Fifty Hereford cows and two bulls doze in the waste of morning feed, and the rabbits work around them, pulling alfalfa stems from the packed snow with nervous jerks, noses working the sharp air as they chew. The atmospheric pressure has fallen rapidly since dark. Strung tight, they scour the trampled ground, erupting in exaggerated leaps at the chalky crunch of snow under a cow’s hoof. They’ve come on trails, hundreds of rabbits in single file, and they leave the same way, following the paths beaten by cows coming to water, by pickups checking on cows. Off the trails, they leave body prints in the loose powder, no crust to support their weight. Scattering out of sight of the buildings, they settle in the shelter of cutbanks, under willows along the creek, in snow domes roofed by the spread of tall sagebrush, digging into the drifts and turning to face south. It’s twenty-five below zero now and quiet, but something is coming. They can smell it.” (42)

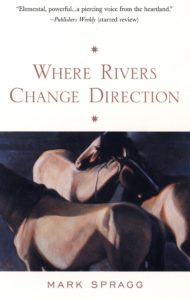

Where Rivers Change Direction by Mark Spragg

“It is easiest for me to remember the land. I close my eyes, and the heat of midsummer swells through me. I see tar-black butterflies at work in the meadows along the Shoshone River, the grasses come thick in seedheads. I smell white-cupped blossoms, bursts of lavender, the weedy scent of the bloodred Indian paintbrush, the overpowering tang of the banks of low-growing sage. I can step my memory onto the backs of the big boulders and hear my boots scuff against the black and rust and corn-yellow lichens that covered them.

“When I was a boy I knew only that the lodge was six miles from the east gate to Yellowstone National Park. I knew it was on the Shoshone National Forest, but I did not know I lived on the largest block of unfenced wilderness in the lower forty-eight states. That is what I know as a man. As a boy I knew only that I was free on the land. If asked where I lived, I replied, ‘Wyoming.’ I meant the northwestern corner of the state; parts of Idaho and Montana. I meant the country itself—a wild, unspoiled part of the earth.” (2)

Perma Red by Debra Magpie Earling

“’Baptiste has seen a salamander,’ he called, ‘a lizard turn red.’

“Louise’s great-grandmother, Good Mark, shut the corral gate and made his way up to Baptiste. Louise stood silent beside her grandmother. The other men had stopped working and had turned to see what was troubling Baptiste. The horses crowded one corner of the corral as the workers gathered at the bottom of the hill. The men crouched suddenly to the ground. They were patting the dirt, searching, feeling for something. She could see Good Mark weaving his fingers through the faded grass, his white braids were tucked in his belt. Louise’s mother shook her head, then cupped her hands together on top of her head. Louise’s grandmother tapped Louise. ‘Look for a lizard,’ she had told Louise, half-whispering. ‘See if you can find the lizard.’

“Louise got down on her hands and knees with the men. She combed the grass with her fingertips. She picked up a branch and brushed the ground but she saw nothing. Baptiste Yellow Knife crept up behind her and Louise looked up to see his knife-bladed hair, his dark face. ‘You won’t find it,’ he said. She pushed at his feet, but he did not budge. ‘Move,’ she said. She didn’t like being told by Baptiste, a boy she barely knew, that she couldn’t do something. ‘You’re in my way,’ she told him. She turned over stones, picking at the sage and grass, looking. She glanced at Baptiste and noticed his watching was dim. His eyes lazy. His lashes flickered and she saw the glare of the black irises swirling back in his head, and then only the whites of his eyes, spooky, almost blue. ‘It won’t do no good,’ he said, his dizzy eyes closed. ‘Someone will die.’ Louise saw the dirt in the slim cuff of Baptiste Yellow Knife’s pants. She saw clouds bleaching to wind, a haze of dust changing light like silt changes water. She was her grandmother standing on the hill, and then Old Macheese was falling back, falling, while the wind lifted her olive scarf from her head. (6)

This House of Sky by Ivan Doig

“Memory is a set of sagas we live by, much the way of the Norse wildmen in their bear shirts. That such rememberings take place in a single cave of brain rather than half a hundred minds warrened into one another makes them sagas no less. By now, my days would seem blank, unlit, if these familiar surges could not come. A certain turn of the desk chair, and the leather cushion must creak the quick dry groan of a saddle under my legs—and my father’s and his father’s. The taste in the air as rain comes over the city is forever a flavor back from a Montana community too tiny to be called a town. A man, the same alphabet of college degrees after his name as mine, trumps in a debating point during a party argument, and my grandmother’s words mutter in me on cue that he grins like a jackass eating thistles.” (10)

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.