Dust off your formal wear and break out the bubbly because the National Book Awards (a.k.a. the Oscars of the book world) are nearly upon us. Yes, in just a few short hours, five dumbstruck authors will be fêted, garlanded, and welcomed into the American literary pantheon.

For those of you who’ve never heard of the National Book Awards, allow allow us to elucidate: every Fall the National Book Foundation nominates twenty-five books across five categories (Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry, Translated Literature, and Young People’s Literature) with the winners being announced at a glitzy November ceremony in New York City.

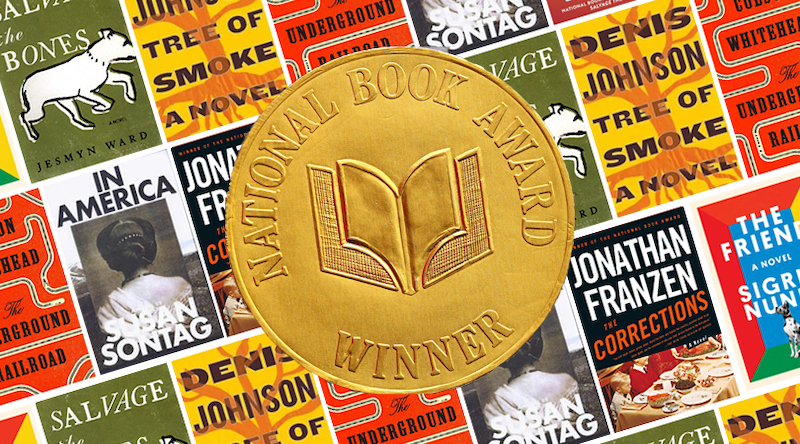

Now in their 71st year, the awards are considered by many to be the country’s most prestigious literary honor, and have, in times gone by, been won by such titans as Ralph Ellison, William Faulkner, Saul Bellow, Flannery O’Connor, Don DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy, Annie Proulx, Susan Sontag, and Colson Whitehead, to name but a few.

As we await the announcement of this year’s winners, here’s a list of the twenty previous fiction honorees of this still-young century (you can check out the nonfiction list here).

*

2019

Trust Exercise by Susan Choi

(Henry Holt & Co.)

Thoughts are often false. A feeling’s always real. Not true, just real.

“Choi’s new novel, her fifth, is titled Trust Exercise, and it burns more brightly than anything she’s yet written. This psychologically acute novel enlists your heart as well as your mind. Zing will go certain taut strings in your chest … Choi gets the details right: the mix tapes, the perms, the smokers’ courtyards, the ‘Cats’ sweatshirts, the clove cigarettes, the ballet flats worn with jeans, the screenings of ‘Rocky Horror,’ the clinking bottles of Bartles & Jaymes wine coolers … Choi builds her novel carefully, but it is packed with wild moments of grace and fear and abandon. She catches the way certain nights, when you are in high school, seem to last for a month—long enough to sustain entire arcs of one’s life … The plot fast-forwards about 15 years. Minor characters become major, damaged ones. I do not want to give too much of this transformation away, because I found the temporary estrangement that resulted to be delicious and, in its way, rather delicate.”

-Dwight Garner, The New York Times

2018

The Friend by Sigrid Nunez

(Riverhead)

Your whole house smells of dog, says someone who comes to visit. I say I’ll take care of it. Which I do by never inviting that person to visit again.

“I don’t know whether or not The Friend is a good novel or even, strictly speaking, if it’s a novel at all—so odd is its construction—but after I’d turned the last page of the book I found myself sorry to be leaving the company of a feeling intelligence that had delighted me and even, on occasion, given joy … The dog, the suicide, the writing life: These are the three strands of thought and feeling that make up the weave of The Friend. They don’t always mesh or make a satisfying design, but they are held together by the tone of the narrator’s voice: light, musing, curious, and somehow wonderfully sturdy … The heartbreak inscribed in those final words fills the page to the margin and beyond with the penetrating loneliness—the sheer textured burden of life itself—that all of Sigrid Nunez’s fine writing had been at brilliant pains to keep both within sight and at bay … From beginning to end, I thought myself engaged.”

–Vivian Gornick, Bookforum

2017

Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward

(Scribner)

Sorrow is food swallowed too quickly, caught in the throat, making it nearly impossible to breathe.

“Ward’s characters are much more than their scars. The novel suggests that you have resources to get you through, regardless of your circumstances. Some of those resources are not tallied by experts. The ear might be a better way of finding those resources than looking at numbers on a spreadsheet. And it takes a certain kind of ear … She [Ward] accepts—perhaps welcomes—her characters, with all their flaws … Sing, Unburied, Sing honors paying attention: seeing, listening, and, finally, singing. The novel inspires me to think that we need new songs, new ways of seeing, new ways of listening.”

–Anna Deavere Smith, The New York Review of Books

2016

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

(Doubleday)

Stolen bodies working stolen land. It was an engine that did not stop, its hungry boiler fed with blood.

“…a potent, almost hallucinatory novel that leaves the reader with a devastating understanding of the terrible human costs of slavery. It possesses the chilling matter-of-fact power of the slave narratives collected by the Federal Writers’ Project in the 1930s, with echoes of Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, and brush strokes borrowed from Jorge Luis Borges, Franz Kafka and Jonathan Swift … [Whitehead] has told a story essential to our understanding of the American past and the American present.”

–Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

2015

Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson

(Random House)

The truth is, though, that you don’t need to die to know what it’s like to be a ghost.

“As with The Orphan Master’s Son, there’s a great deal of comedy to be found in Fortune Smiles, though the humor in this new book is offset by a darkness so pervasive I found it seeping into my daily life. Despairing men are at the heart of each of these tales, most of them protagonists on the cusp of being antagonists … Each of these stories plants a small bomb in the reader’s head; life after reading Fortune Smiles is a series of small explosions in which the reader—perhaps unwillingly—recognizes Adam Johnson’s gleefully bleak world in her own … the stories in Fortune Smiles may be best appreciated when taken out into the sunshine one by one.”

–Lauren Groff, The New York Times Book Review

2014

Redeployment by Phil Klay

(Penguin Press)

She spent all his combat pay before he got back, and she was five months pregnant, which, for a Marine coming back from a seven-month deployment, is not pregnant enough.

“Klay succeeds brilliantly, capturing on an intimate scale the ways in which the war in Iraq evoked a unique array of emotion, predicament and heartbreak. In Klay’s hands, Iraq comes across not merely as a theater of war but as a laboratory for the human condition in extremis … Each story calls forth a different dilemma or difficult moment, nearly all of them rendered with an exactitude that conveys precisely the push-me pull-you feelings the war evoked: pride, pity, elation and disgust, often pulsing through the same character simultaneously … Klay has a nearly perfect ear for the language of the grunts—the cursing, the cadence, the mixing of humor and hopelessness. They are among the best passages in the book, which, unfortunately, are unfit for a family newspaper.”

–Dexter Filkins, The New York Times Sunday Book Review

2013

The Good Lord Bird by James McBride

(Riverhead)

The Good Lord Bird don’t run in a flock. He Flies alone. You know why?

He’s searching. Looking for the right tree.

“… a boisterous, highly entertaining, altogether original novel … Mistake follows mistake in this rambunctious comedy of errors, and Old Man Brown and his hard-riding horde head straight to the Kansas flatlands to rescue 11-year-old Henrietta from slavery … There is something deeply humane in this, something akin to the work of Homer or Mark Twain. We tend to forget that history is all too often made by fallible beings who make mistakes, calculate badly, love blindly and want too much. We forget, too, that real life presents utterly human heroes with far more contingency than history books can offer.”

–Marie Arana, The Washington Post

2012

The Round House by Louise Erdrich

(Harper)

Now that I knew fear, I also knew it was not permanent. As powerful as it was, its grip on me would loosen.

It would pass.

“Erdrich’s plotting is masterfully paced: the novel, particularly the second half, brims with so many action-packed scenes that the pages fly by. And yet the author also knows just when to slow down, reminding us that despite everything upending Joe’s life, he’s still just a teenager … One of the most pleasurable aspects of Erdrich’s writing is that while her narratives are loose and sprawling, the language is always tight and poetically compressed … There’s nothing, not the arresting plot or the shocking ending of The Round House, that resonates as much as the characters. It’s impossible to stop thinking about the devastating impact the desire for revenge can have on a young boy.”

–Molly Antopol, The San Francisco Chronicle

2011

Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward

(Bloomsbury)

I will not let him see until none of us have any choices about what can be seen, what can be avoided, what is blind, and what will turn us to stone.

“Jesmyn Ward makes beautiful music, plays deftly with her reader’s expectations: where we expect violence, she gives us sweetness. When we brace for beauty, she gives us blood … Best of all, she gives us a singular heroine who breaks the mold of the typical teenage female protagonist. Esch isn’t plucky or tomboyish. She’s squat, sulky and sexual. But she is beloved—her brothers Randall, Skeetah and Junior are fine and strong; they brawl and sacrifice and steal for her and each other. And Esch is in bloom … For all its fantastical underpinnings, Salvage the Bones is never wrong when it comes to suffering. Sorrow and pain aren’t presented as especially ennobling. They exist to be endured—until the next Katrina arrives to ‘cut us to the bone.’”

–Parul Sehgal, The New York Times Sunday Book Review

2010

Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon

(McPherson & Co.)

I was an easy birth, and I have never regretted it. Not even for a visit would I return to the womb.

“Void and menace are the operating principles in Lord of Misrule. First, it’s hard to sort the men from the horses, so similar are their slaveries, their striving for nothing, their tendency to be ruled by lesser animals … This rich, soupy (as in primal soup, many ingredients) milieu that Gordon creates—all the names and hints of back story glimmering in the dust—serve to make a character shine, really shine, when he or she rises up and out. You hear chains popping all through this novel, little acts of will and big acts of self-determination. It’s astonishing how quickly, with all this description, Gordon can get to a philosophical point or make a character unforgettable.”

–Susan Salter Reynolds, Los Angeles Times

2009

Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann

(Random House)

The thing about love is that we come alive in bodies not our own.

“Through a Joycean tangle of voices—including that of a fictionalized Petit—he weaves a portrait of a city and a moment, dizzyingly satisfying to read and difficult to put down … Like Joyce’s Ulysses—also a portrait of a city and a day—the chapters’ formats and prose styles vary widely … Not everyone here is admirable, but all are depicted with sympathy and care. Each leaves its own color on the book’s canvas and then departs; no narrator is repeated except the tightrope walker, the conductor who has brought this orchestra together.”

–Moira Macdonald, The Seattle Times

2008

Shadow Country by Peter Matthiessen

(Modern Library)

This world is painted on a wild dark metal.

“…a novel of Faulknerian power and darkness, one that embraces the American experience from the time of the Civil War to the first years of the Depression … While Shadow Country gradually conveys what is known about Watson from records and reminiscences, Matthiessen imagines conversations and the background for certain characters and encounters, even as he deepens the ambiguities of his increasingly tantalizing story … While Book I draws on the down-home voices of the islanders and Book II uses the prose of a good reporter, Book III is written in a rather formal, old-fashioned style, suitable for the scion of proud, if now indigent, Southern aristocrats … Shadow Country is altogether gripping, shocking, and brilliantly told, not just a tour de force in its stylistic range, but a great American novel, as powerful a reading experience as nearly any in our literature.”

–Michael Dirda, The New York Review of Books

2007

Tree of Smoke by Denis Johnson

(FSG)

She had nothing in this world but her two hands and her crazy love for Jesus, who seemed, for his part, never to have heard of her.

“It’s a powerful story about the American experience in Vietnam, with unsettling echoes of the current American experience in Iraq … Skip believes in the goodness and promise of America with boyish innocence and ardor…Skip’s innocence, however, is tarnished when he witnesses the agency’s brutal assassination of a priest (falsely suspected of running guns) in the Philippines, and in Vietnam he quickly becomes lost in the wilderness of mirrors created by his fellow intelligence officers … Mr. Johnson intercuts the stories of Skip and the colonel with those of half a dozen other people caught up in the war … Mr. Johnson not only succeeds in conjuring the anomalous, hallucinatory aura of the Vietnam War as authoritatively as Stephen Wright or Francis Ford Coppola, but he also shows its fallout on his characters with harrowing emotional precision.”

–Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

2006

The Echo Maker by Richard Powers

(FSG)

Nothing anyone can do for anyone, except to recall: We are every second being born.

“The Echo Maker is not an elegy for How We Used to Live or a salute to Coming to Grips, but a quiet exploration of how we survive, day to day … The faith we extend to writers like Weber is, I think, the same kind of faith we put in our best fiction writers. We expect—and need—them to tell us of our world, how things work, how against all odds we make it through. With The Echo Maker, Richard Powers vindicates this faith, employing his trademark facility with all manner of esoteric discourse, but never letting it overcome the essential human truth of his characters … I haven’t mentioned the expert plot mechanics yet, Powers’s array of tiny enigmas and red herrings, all perfectly paced … As the features of life after 9/11 come into focus, Powers accomplishes something magnificent, no facile conflation of personal catastrophe with national calamity, but a lovely essay on perseverance in all its forms.”

–Colson Whitehead, The New York Times Book Review

2005

Europe Central by William T. Vollmann

(Viking)

Maybe life is a process of trading hopes for memories.

“Vollmann’s [novel] is a hall of mirrors—each tale getting a kind of sister story that forms its opposite image. Enter the book, take a twirl around, and you are presented with a kind of kaleidoscopic portrait of life in Europe around the dawn of World War II, when totalitarianism was on the rise. Try to find your way out and you will become, well, a little lost. This sense of claustrophobia and confusion is, one imagines, purposeful, as Europe Central aims to show how totalitarianism occurred and how it felt on the inside, and to bring us up close and personal with the nubbly texture of history.”

–John Freeman, The Boston Globe

2004

The News From Paraguay by Lily Tuck

(Harper Perennial)

Surprising yourself is a big thing for me—to go somewhere that I don’t even know I’m going.

“The historical novel The News From Paraguay finds its epic story in an important political crossroads for Paraguay … Like a slowly opening fan whose slats reveal themselves one by one, so do the many stories within The News From Paraguay. Tuck’s omniscient narrator finds an interesting tale in just about every character and encounter. Each brief self-contained diversion—whether of Ella’s maid having her broken arm amputated or a doctor’s fatal spill after urinating in a lake—crystallizes the whole in miniature.”

–Linda Burnett, The San Francisco Chronicle

2003

The Great Fire by Shirley Hazzard

(FSG)

My need of your words: for such closeness there should be a word beyond love.

” …a classic romance so cleverly embedded in a work of clear-eyed postwar sagacity that readers will not realize until halfway through that they are rooting for a pair of ill-starred lovers who might have stepped off a Renaissance stage … This is not a novel of war and its aftermath so much as a study of how people act, and how they are acted upon, in the wake of violent disruption. After you shake the chessboard, how will the pieces realign themselves? … The greatest pleasure is her subtle and unexpected prose…Never lyrical for the sake of lyricism, [it] follows the sensible course of her characters—open to beauty and alert to its dangers.”

–Regina Marler, Los Angeles Times

2002

Three Junes by Julia Glass

(Pantheon)

I, too, seem to be a connoisseur of rain, but it does not fill me with joy; it allows me to steep myself in a solitude I nurse like a vice I’ve refused to vanquish.

“Julia Glass has written a radiant first novel that turns the story of Scotland native Fenno McLeod and his real and extended family of ‘upper-crusty Ivanhoe’ types, creative women and urban gay men into an intimate literary triptych of lives pulled together and torn apart … Paul’s story is a finely detailed portrait of a somewhat ordinary life and the handful of people, past and present, who make their way into it. But the novel’s most sustained scrutiny is reserved for Fenno, Paul’s bibliophile eldest son who has a preference for men and remains devoted to the mother whose passionate life, tragically cut short by lung cancer, he never really understood. Fenno’s lengthy first-person narrative takes its place at the literal and symbolic center of Three Junes, providing the anchor point for the intricate web of characters that make up Glass’ thoughtful textual design.”

–Laura Ciolkowski, The Chicago Tribune

2001

The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen

(Picador)

Elective ignorance was a great survival skill, perhaps the greatest.

“Franzen shores up his Zeitgeist-heavy narrative with the indispensable masonry of a carefully crafted plot, exuberant yet plausible satire and, most of all, closely observed character … Franzen narrates The Corrections with a subdued, assured and compassionate touch. The result is an energetic, brooding, open-hearted and funny novel that addresses refreshingly big questions of love and loyalty in America’s rapidly fragmenting, meaning-challenged domestic sphere … What happens to the Lamberts is ultimately less compelling than the simple fact of them, as rendered in Franzen’s patient, wise descriptions of their petty trials, their epic self-deceptions and their astonishing, resilient need of one another.”

–Chris Lehmann, The Washington Post

2000

In America by Susan Sontag

(Picador)

Each of us carries a room within ourselves, waiting to be furnished and peopled, and if you listen closely, you may need to silence everything in your own room, you can hear the sounds of that other room inside your head.

“In America is a picaresque fable, a historical tragicomedy. The story revolves around a Polish actress, Maryna Zalezowska. More than an actress, she is a national symbol for the triply besieged and conquered Poland, a symbol of patriotism, of seriousness, of achievement on a grand scale in the arts … [Sontag] is giving us, in fiction, the history of the loss that led to irony and fragmentation, the death of so much that could formerly be called culture, and she bravely attempts a journey beyond that loss. Sontag has managed to structure a paradox—call it hopeful inconsolability or optimistic pessimism—a belief that the destruction of our ideals and our long-lost innocence can still be narrated, that there is still a story to be told about us and about how we came to be the way we are or to see.”

–Michael Silverblatt, Los Angeles Times