Death is like an old whore in a bar–I’ll buy her a drink but I won’t go upstairs with her

*

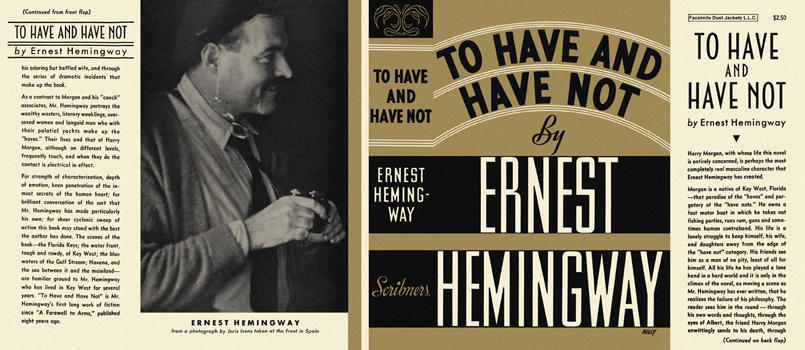

“This is Mr. Hemingway’s first novel since A Farewell to Arms was published eight years ago. He has in the meantime produced a volume of short stories, Winner Take Nothing, and two other books, Death in the Afternoon and Green Hills of Africa. He has been, since he was first published, a normally productive writer. It would be pleasant to add that he is also a writer who has grown steadily in stature as well as in reputation. But this, unfortunately, would not be the truth. His skill has strengthened, but his stature has shrunk.

Perhaps this last statement has a paradoxical sound. I mean simply that what discipline could add to talent has, in his case, been added. He has moved steadily toward mastery of his technique, though that is by no means the perfect instrument it has been praised for being. Technique, however, is not enough to make a great writer, and that is what we have been asked to believe Mr. Hemingway was in process of becoming. The indications of such a growth are absent from this book, as they have been absent from everything Mr. Hemingway has written since A Farewell to Arms. There is evidence of no mental growth whatever; there is no better understanding of life, no increase in his power to illuminate it or even to present it. Essentially, this new novel is an empty book.

Such statements, naturally, demand to be amplified. Mr. Hemingway has been for some years an outstanding figure in American literature; he has influenced greatly men a little younger than himself, and they have paid him the tribute of imitation. Whatever he does is of interest because he has, unquestionably, a very real talent. What has he done with it in To Have and Have Not?

“The human will, in Hemingway, as some percipient critics have already pointed out, approaches the vanishing point. As Mr. John Peale Bishop wrote, in that brilliant analysis of Hemingway which appeared in After the Genteel Tradition, in his novels ‘men and women do not plan; it is to them that things happen. In the telling phrase of Wyndham Lewis, the “I” in Hemingway’s stories is “the man that things are done to.”‘

Nor does Mr. Hemingway help his case by the introduction of his hand-picked specimens of the idle rich and their parasites, and of the morally rotten whom he shows us in brief close-ups…They are people who, in one form or another, have existed in every age. They are not to be laid on the doorstep of economic royalism. This is adolescent thinking, though the writing is maturely skilled.

The expertness of the narrative is such that one wishes profoundly it could have been put to better use. There is cumulative power and telling economy of phrase. There is driving action. And there is also pointless brutality, passages of purely sadistic writing. The famous Hemingway dialogue reveals itself as never before in its true nature. It is false to life, cut to a purely mechanized formula. You cannot separate the speech of one character from another and tell who is speaking. They all talk alike.

In spite of its frequent strength as narrative writing, To Have and Have Not is a novel distinctly inferior to A Farewell to Arms. There is nothing in it comparable to the final chapter of the earlier book, or to the story of the retreat from Caporetto. Mr. Hemingway’s record as a creative writer would be stronger if it had never been published.”

–J. Donald Adams, The New York Times, October 17, 1937