Elizabeth Hardwick, who was born 102 years ago last month, was one of the foremost essayists and literary critics of her era, as well as an extremely accomplished novelist and short story writer in her own right. An intellectual powerhouse often credited with expanding the possibilities of the literary essay through her incisive, witty, freewheeling style of writing, Hardwick was fiercely invested in the literary landscape of the time (perhaps most infamously demonstrated by her 1959 Harper’s essay, “The Decline of Book Reviewing“—a scathing take-down of the way books were being reviewed in American periodicals). She produced at least one bonafide masterpiece of fiction in her semi-autobiographical novel Sleepless Nights (1979), and was the co-founder of The New York Review of Books, for which she wrote for over forty years.

As Lauren Groff wrote last month in her wonderful New York Times essay, “In Praise of Elizabeth Hardwick“:

I delight in her wit and intelligence, and find her criminally underappreciated by bookish people, perhaps because she is subtle, and because her light beams outward into the world, not back to illuminate herself. She shows us the many ways of being a human, if we could only look harder and love more deeply all that we’re seeing.

There is such sympathy in Hardwick’s fleeting glances; it feels that each character, writer, or book she considers is held, for a moment, in her generous yet unsparing palm. Her sympathy extends all the way to the exhausted reader, the heartbroken reader, the reader who, like Bartleby, would prefer not to engage with the world, the reader who is too frightened or anxious or weary or sick; this reader too is carried along with Hardwick’s fine intelligence. With Elizabeth Hardwick as a guide, for a minute or for a long white night, one can almost forget the darkness pressing in.

Eager to reacquaint ourselves with her prodigious talent, with that light she beamed outward into the world, we took a look back through the archives of The New York Review of Books, and picked out eight of our favorite Elizabeth Hardwick book reviews.

*

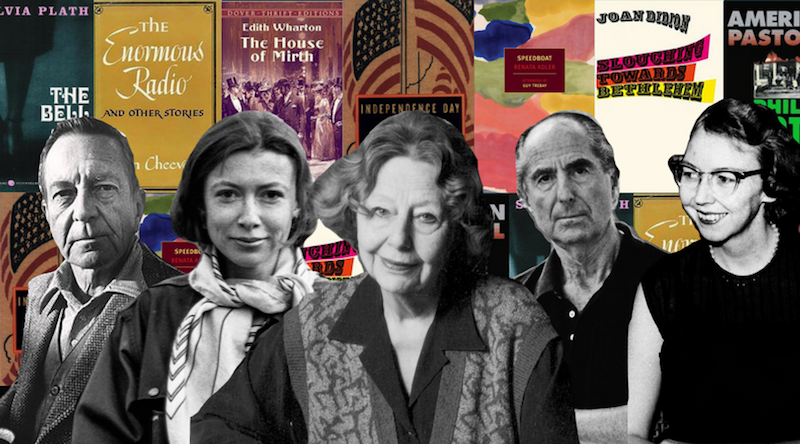

On Philip Roth and American Pastoral:

“The structure of Roth’s fiction is based often upon identifying tirades rather than actions and counter-actions, tirades of perfervid brilliance, and this is what he can do standing on his head or hanging out the window if need be. The tirades are not to be thought of as mere angry outbursts in the kitchen after a beer or two, although they are usually angry enough since most of the characters are soreheads of outstanding volubility. The monologues are a presentation of self, often as if on the stage of some grungy Comédie Française, if such an illicit stretch may be allowed.

…

“That the Levov family is to suffer, by way of Merry, a catastrophe remote in a statistical sense, undermines the interesting close calls on the road of the Swede’s American journey. The Swede has made a right turn into the highway of assimilation and this, it appears, is the true direction of the novel’s intellectual and fictional energy.

…

“American Pastoral is a sort of Dreiserian chronicle of the Levov family. Their painfully built fortune, even without the disgrace, might have declined owing to obsolescence, slower than a bomb, but going by the name of bankruptcy. Maids have not for some decades been in need of the finely stitched, soft leather gloves in matching colors. Gloves, except on the coldest winter days, have gone the way of the ribbon shops in the West Thirties of Manhattan, ribbons for hats that were to go on the heads of proper women whenever they left the house.

Still the saga of the Levov family is a touching creative act and in the long line of Philip Roth fiction can be rated PG, suitable for family viewing—more or less.”

–The New York Review of Books, June 7, 1997

*

On the novels of Joan Didion:

“Joan Didion’s novels are a carefully designed frieze of the fracture and splinter in her characters’ comprehension of the world. To design a structure for the fadings and erasures of experience is an aesthetic challenge she tries to meet in a quite striking manner; the placement of sentences on the page, abrupt closures rather like hanging up the phone without notice, and an ear for the rhythms and tags of current speech that is altogether remarkable. Perhaps it is prudent that the central characters, women, are not seeking clarity since the world described herein, the America of the last thirty years or so, is blurred by a creeping inexactitude about many things, among them bureaucratic and official language, the jargon of the press, the incoherence of politics, the disastrous surprises in the mother, father, child tableau.

The method of narration, always conscious and sometimes discussed in an aside, will express a peculiar restlessness and unease in order to accommodate the extreme fluidity of the fictional landscape. You will read that something did or did not happen; something was or was not thought; this indicates the ambiguity of the flow, but there is also in ‘did or did not’ the author’s strong sense of a willful obfuscation in contemporary life, a purposeful blackout of what was promised or not promised—a blackout in the interest of personal comfort, and also in the interest of greed, deals, political disguises of intention.

Joan Didion’s novels are not consoling, nor are they notably attuned to the reader’s expectations, even though they are fast-paced, witty, inventive, and interesting in plot. Still they twist and turn, shift focus and point of view, deviations that are perhaps the price or the reward that comes from an obsessive attraction to the disjunctive and paradoxical in American national policy and to the somnolent, careless decisions made in private life.”

–The New York Review of Books, October 31, 1996

*

On Richard Ford and Independence Day:

“In passing it might be remarked that Ford is the first, if memory serves, to give full recognition to the totemic power in American life of the telephone and the message service…In Frank Bascombe’s world a good deal of the information necessary to move forward is given over the phone.

(Recently, in the O.J. Simpson trial, the prosecution, following week after wearying week, month after month building its beaver dam of circumstantial particulars, spent quite a lot of time with the record of O.J.’s car phone around the time projected for the murders. The record keeper for the phone company dutifully went down the list, the purpose seeming to be that the number of busy signals and no-answers might slip into the mind of the jurors as yet another twig forming the rage that led to double homicide. No-answer motivation.)

Independence Day, if you’re taking measurements like the nurse in a doctor’s office, might be judged longer than it need be. But longer for whom? Every rumination, each flash of magical dialogue or unexpected mile on the road with a stop at the pay phone, is a wild surprise tossed off as if it were just a bit of cigarette ash by Richard Ford’s profligate imagination. The Sportswriter and Independence Day are comedies—not farces, but realistic, good-natured adventures, sunny, yes, except when the rain it raineth everyday. The new work, Independence Day, is the confirmation of a talent as strong and varied as American fiction has to offer.”

–The New York Review of Books, August 10, 1995

*

On the novels of Edith Wharton:

“There is a tradesman’s shrewdness in Edith Wharton’s work. She knows how to order the stock and dispose the goods in the window. She was a popular author, or, to be more just, her books were popular, not always the same thing. (Even in her day there were writers, many of them women susceptible to sentiment, who trafficked in novels in the present-day manner—more soy beans on the commodities market.) Edith Wharton is free of lush sentiments and moralizing tears. In The House of Mirth, her triumph, she is not always clear what the moral might be and thereby created a stunning tragedy in which the best and the richest society of New York revealed an inner coarseness that might remind one of pimps cruising in their Cadillacs.

…

“In her novels Manhattan is nameless, bare as a field, stripped of its byways, its fanciful, fabricated, overwhelming reality, its hugely imposing and unalterable alienation from the rest of the country—the glitter of its beginning and enduring modernity as a world city.”

–The New York Review of Books, January 21, 1988

*

On Renata Adler and Speedboat:

“Perhaps we cannot ask for a novel. We can at most discover the terms of a ‘novel.’ In the reviews of Renata Adler’s Speedboat, a work of unusual interest, many critics asked whether this ‘novel’ was really a novel. The book is, in its parts, fastidiously lucid, neatly and openly composed. It is the linear as opposed to the circular construction that leads to the withholding of consent for the enterprise, at least on the part of some readers.

…

“To be interesting, each page, each paragraph—that is the burden of fiction which is made up of random events and happenings in sequence. Speedboat is very clear about the measure of events and anecdotes, and it does meet the demand for the interesting in a nervous, rapid, remarkably gifted manner. A precocious alertness to incongruity: this one would have to say is the odd, dominating trait of the character of the narrator, the only character in the book. Perception, then, does the work of feeling and is also the main action. It stands there alone, displacing even temperament.

For the reader of Speedboat, certain things may be lacking, particularly a suggestion of turbulence and of disorder more savage than incongruity can bear. But even if feeling is not solicited, randomness itself is a carrier of disturbing emotions. In the end, a flow is more painful than a circle, which at least encloses the self in its resolutions, retributions, and decisions.”

–The New York Review of Books, November 25, 1976

*

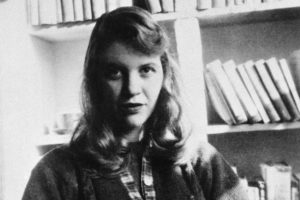

On Sylvia Plath and The Bell Jar:

“In Sylvia Plath’s work and in her life the elements of pathology are so deeply rooted and so little resisted that one is disinclined to hope for general principles, sure origins, applications, or lessons. Her fate and her themes are hardly separate and both are singularly terrible. Her work is brutal, like the smash of a fist; and sometimes it is also mean in its feeling. Literary comparisons are possible, echoes vibrate occasionally, but to whom can she be compared in spirit, in content, in temperament?

…

“For all the drama of her biography, there is a peculiar remoteness about Sylvia Plath. A destiny of such violent self-definition does not always bring the real person nearer; it tends, rather, to invite iconography, to freeze our assumptions and responses. She is spoken of as a ‘legend’ or a ‘myth’—but what does that mean? Sylvia Plath was a luminous talent, self-destroyed at the age of thirty, likely to remain, it seems, one of the most interesting poets in American literature. As an event she stands with Hart Crane, Scott Fitzgerald, and Poe rather than with Emily Dickinson, Marianne Moore, or Elizabeth Bishop.

…

“It is not recklessness that makes Sylvia Plath so forbidding, but destructiveness toward herself and others. Her mother thought The Bell Jar represented ‘the basest ingratitude’ and we can only wonder at her innocence in expecting anything else. For the girl in the novel, a true account of events so far as we know, the ego is disintegrating and the stifling self-enclosure is so extreme that only death—and after that fails, shock treatment—can bring any kind of relief. Persons suffering in this way simply do not have room in their heads for the anguish of others—and later many seem to survive their own torments only by an erasing detachment. But even in recollection—and The Bell Jar was written a decade after the happenings—Sylvia Plath does not ask the cost.

There is a taint of paranoia in her novel and also in her poetry. The person who comes through is merciless and threatening, locked in violent images. If she does not, as so many have noticed, seem to feel pity for herself, neither is she moved to self-criticism or even self-analysis. It is a sour world, a drifting, humid air of vengeance.”

–The New York Review of Books, August 12, 1971

*

On the fiction of Flannery O’Connor:

“Flannery O’Connor was a brilliant writer. Her fiction was, above all, unexpected and disturbing and she herself was an unexpected, extraordinary person, not much like other people. The cruel suffering she endured for such a long time, her death at the age of thirty-eight, fill those who knew her with pain. I first met her when she was very young and writing Wise Blood. I remember that I found that book somehow difficult to like at the beginning. It was so fierce, so hard, so plainly, downrightly unusual. And yet, of course, I did finally like Wise Blood (you can’t easily hold out against Hazel Motes) even if I did like better the marvelous short stories, collected in A Good Man is Hard to Find. But where had all this come from? one was always asking oneself. The author had led a secluded life. She was a Roman Catholic, of Irish extraction, born and brought up in Georgia. Most of all she was like some quiet, puritanical convent girl from the harsh provinces of Canada. Her work was utterly different; it was Southern, rural, wicked, with a nearly inexplicable knowledge of the deformed and sinful, the all-too-deeply experienced. She was fascinated by street preachers, ignorant and insisting fundamentalists, by maimed persons with a matchless commitment to their grotesque destinies. She saw everything with a severe humor, local enough in accent, but more detached, more difficult to define than most other Southern writing.

…

“In everything of Flannery O’Connor’s we are aware of her intense preoccupation with the ragged remnants of Protestantism, those hungry sectarians, those wandering souls with the Answer, those diviners of Revelations, and receivers of code messages from the Holy Spirit. Nearly every plot development turns in this direction.

…

“Flannery O’Connor’s brilliant talent was of that sort that has a contradiction in every pore. She was, indeed, a Catholic writer, also a Southern writer; but neither of these traditions prepares us for the oddity and beauty of her lonely fiction.”

–The New York Review of Books, October 8, 1964

*

On the stories of John Cheever:

“John Cheever’s literary career is like one of those graphs of the movements of the middle class after the war. He, like they, is seeking some lonely corner of beauty and truth, some ‘real’ place exempt from the disfigurations he has fled. The compulsion, in Cheever, to move on is perplexing since his most valuable bit of inventory is his knowledge of the slummy asphalt alleys of the middle class.

…

“In [the Wapshot] novels one has the sense that Cheever is in flight from the manners and belongings of the new middle class. Flee them most of us will, but they are, still, just a footnote. How can anyone think that our despair is contained in the decorative, the purely social mannerism? Fiction that sees modern horror in our manufactures and looks for redemption in the absurdities of funny, old, impossible people is not in despair but in a state of guilt over well-being. To yearn for the sense of ‘identity’ that came from a fixed town and fixed family position is depressing; one cannot, in any case, avoid a sense of ‘identity.’ You can see eternity in a grain of sand, but not in the grain of the wood on the dining room table. In these two novels the strength of romantic fantasy clutches at everything, even the modern ‘realistic’ half.

…

“Of all Cheever’s work, the stories collected in The Enormous Radio are the most memorable. Janitors, young couples, call girls, homosexuals, divorced people, miserable children, people moving from one apartment to another—many of the details of New York in the 1940s are preserved with great fidelity and beauty. The style is very pure, as in ‘A Pot of Gold.’ ‘Ralph was a fair young man with a tireless commercial imagination and an evangelical credence in the romance and sorcery of business success.’ This desolate story of the failed young executive has the simplicity and truth of some old American tale. In the suburban stories, mystification begins to fog the surface of things. The very plausibility, typicality of the scene invites it.

…

“It is hard to place the stories of John Cheever. His special note is tender-heartedness: at his best he is given to suffering, not to satire, and that gives his suburban and city families their sweet, rather pitiful reality. If he has a master, it is probably F. Scott Fitzgerald. At least he has one disciple: John Updike.”

–The New York Review of Books, February 6, 1964

*

Hungry for more Hardwick wisdom? Check out her collected writing advice here