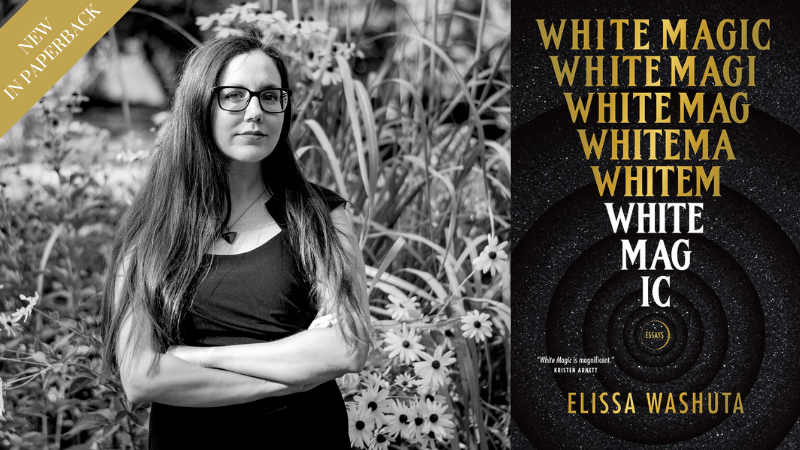

Welcome to the Book Marks Questionnaire, where we ask authors questions about the books that have shaped them. This week, we spoke to the author of White Magic, Elissa Washuta.

*

Book Marks: Last book you read?

Elissa Washuta: I just finished Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics by Richard H. Thaler. I seem to be working on a book about money, and I’m trying to understand what it does. My viewings of The Big Short began offering diminishing returns in that regard, so I have been reading books. There’s a moment in that film in which Thaler joins Selena Gomez to break the fourth wall and explain synthetic collateralized debt obligations to the audience. In the book, he explains some of the basics of behavioral economics with similar friendliness. I’ve spent the year watching finance columnists shake their heads at the irrationality of human behavior in the markets, as though they think they can wait out human behavior until our souls become algorithms, so it’s refreshing to read Thaler’s affirmation that it’s normal for humans to act like humans when it comes to decisions about money.

BM: Book you’re reading right now?

EW: Charles Mackay’s Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, published in the mid-19th century, which I’ve been meaning to read all year but put off because (carrying a memory of, at age 17, trying to comprehend Joyce’s “Ivy Day in the Committee Room” with zero understanding of the politics of early 20th century Ireland) I wasn’t sure I’d be able to get anything from it. It’s a book about economic bubbles, speculation, and group panic: tulip futures, alchemy, the execution of so-called witches. From the preface to the 1869 edition: “Money, again, has often been a cause of the delusion of multitudes. Sober nations have all at once become desperate gamblers, and risked almost their existence upon the turn of a piece of paper. […] Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one.”

BM: A book that blew your mind?

EW: The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine and Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt by Michael Lewis. I read them back to back this summer, and what strikes me about the books, the conversations around them, and the similar conversations about financial markets this year is that even regulators and other people one would expect to understand this stuff do not always understand this stuff—there is just too much complexity in too many areas with too much ongoing development for everyone to keep up with it all. Actually, Flash Boys got a lot of criticism from those on Wall Street who said Lewis’s account was inaccurate, and a lot of the conversation around the book focused on how very complex the plumbing of the market is, and how outsiders are just not going to be able to understand how it all works. I mean… shouldn’t someone other than high-frequency traders be able to understand high-frequency trading, a huge mover of US markets, which affect all of us, whether we participate in them or not? Anyway, I’ll stop talking about the stock market now.

BM: Classic book on your To Be Read pile?

EW: One more money book, sorry. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money by John Maynard Keynes. I need to learn what he actually said about animal spirits and markets staying irrational and all that, rather than more of the market wisdom websites’ misquotes.

BM: What book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

EW: Other Worlds Here: Honoring Native Women’s Writing in Contemporary Anarchist Movements by Theresa Warburton, my settler twin and co-editor of the anthology Shapes of Native Nonfiction. Our books came out around the same time last year, and I think all settler anarchists and others on the left need to read this book.

BM: What book do you think your book is most in conversation with?

EW: The Freezer Door by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore. We were actually neighbors for a while, and we were both working on our books at the time, both taking walks around Seattle, including walks together to the park and back. There’s one event we both write about briefly, and I didn’t know that until I read her book. Formally, I think the two are also in conversation, both using movement and land as central to the structure and subjects of the books.

BM: Favorite book to give as a gift?

EW: As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance by Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. It’s a book I quote constantly, both in speaking and in writing, and it’s a beautiful guide to being human. This is the book that taught me that my ongoing mental and physical responses to trauma are actually normal, because I live in an unhealed world in which I have the potential to be harmed again. And it taught me about “reciprocal recognition, the act of making it a practice to see another’s light and to reflect that light back to them.”

BM: First book you remember loving?

EW: I am a little cat. by Helmut Spanner. It’s a tiny picture book, twenty pages and about two inches by four inches. It’s about the happy life of a little cat. My copy has pages that appear to have been taped back in after falling out, and a few marks of a green crayon.

BM: Favorite re-read?

EW: I very rarely re-read, because I have so many unread books in my house that the floor of my finished attic is actually bowing under the weight. (By the way, if you, like me, have a hundred-year-old house, I recommend talking to an engineer before bringing your entire collection of books to your attic.) The only book I really re-read beyond those I teach is Winter in the Blood by James Welch. It’s short and can trick you into thinking you’ve gotten what it has to offer if you read it too quickly, but the texture of metaphor and subtext is exquisite and complex.

BM: What’s one book you wish you had read during your teenage years?

EW: There are so many, of course, but I’ll say There There by Tommy Orange. Its assemblage of so many characters who are living their Indigeneity in different ways, none of them wrong, none of them less than wholly Native. That was something that took me a long time to reach in understanding myself as a Cowlitz person.

*

Elissa Washuta is a member of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe and a nonfiction writer. She is the author of Starvation Mode and My Body Is a Book of Rules, named a finalist for the Washington State Book Award. With Theresa Warburton, she is co-editor of the anthology Shapes of Native Nonfiction: Collected Essays by Contemporary Writers. She is an assistant professor of creative writing at the Ohio State University.

Elissa Washuta’s White Magic is out now in paperback from Tin House

*

· Previous entries in this series ·