Writing is a socially acceptable form of schizophrenia.

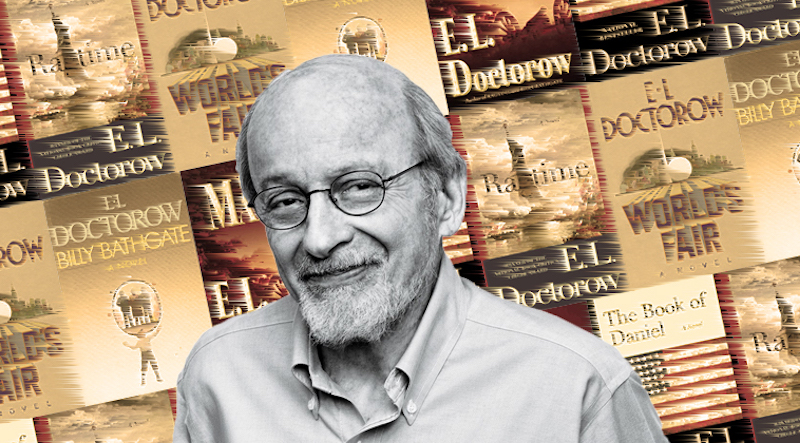

Yesterday, January 6, would have been E. L. Doctorow’s eighty-eight birthday. Considered one of the most important American novelists of the 20th century, Doctorow, who died in 2015, was known for his imaginative manipulation of popular genres, use of unconventional narrative forms, and for placing fictional characters and events within recognizable historical contexts. Perhaps John Updike put it best when he characterized Doctorow as “a reconstructor of history as a visionary who seeks in time past occasions for poetry.”

In a career that lasted over fifty years Doctorow won a National Book Critics Circle Award, a PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, two National Book Critics Circle Awards, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal for Fiction, as well as numerous other accolades.

Below, we look back on a selection of classic reviews of some of Doctorow’s most famous novels—from 1971’s The Book of Daniel (loosely based on the lives, trial and execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg), to 2005’s The March (a multi-perspective recounting of Sherman’s March to the Sea).

*

The Book of Daniel (1971)

We are able to walk on air, but only as long as our illusion supports us.

“Supposedly working on his doctoral thesis, Daniel instead produces notes toward an autobiographical novel about his Old-Left parents, Paul and Rochelle Isaacson, who in the early 1950’s were electrocuted for passing atom-bomb secrets to the Russians … One contemplates most novels based on controversial public happenings with a sinking heart: fictionalization tends to trivialize such events: the public record weighs like sandbags on the imagination. But Mr. Doctorow has turned such liabilities into assets. He freely acknowledges the looming presence of the Rosenberg Case by building a high-tension bridge between reality and fiction.

…

“…there are no schematic answers in The Book of Daniel. Only uneasy ironies. One doesn’t read the novel on the crest of emotion; Mr. Doctorow scrupulously avoids sentiment either cheap or expensive; not a small part of the novel’s fascination lies in the puzzles of its obliquities. But when the time comes for the execution, Doctorow-Daniel does not hold back (‘I suppose you think I can’t do the electrocution. . .I will show you that I can do the electrocution.’)

And he does. And the horror of it is that it brings no release, no pity and fear, no Greek purgation. We weep because the bridge between reality and fiction is still intact, because we are reminded that no one, not even this latter-day prophet and dream-interpreter, can explain why these people died. The last and greatest irony is that the God of the Bible—of the original Book of Daniel—the God who, according to Daniel Lewin’s kid sister, ‘gets people,’ ‘takes care of them,’ ‘lays on his monumental justice,’ has abdicated his throne. The kingdom is divided, but there is no judgment, no handwriting on the wall.”

–Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, The New York Times, June 7, 1971

*

Ragtime (1975)

It was evident to him that the world composed and recomposed itself constantly in an endless process of dissatisfaction.

“This mixture of fact and fiction may confuse or mislead the unwary or historically uninformed reader, and it suggests a projection onto the past of the suspect techniques of the New Journalism. I, for one, although no friend of that aberration, am willing to forgive any historical novelist who makes his flights from historical fact as funny and pertinent as Doctorow makes his. Like Houdini’s audiences, I am made to enjoy being fooled. As to the topical descriptions, they appear to be accurate enough to satisfy an exacting student of Americana. Certainly they are alive enough never to smell the research in old newspaper files that they must have required.

But Ragtime is not social history disguised as a novel; rather it is the novel as social history, an imaginative flight based on the facts of the past but released rather than confined by them, as ragtime’s music’s muted madness is heightened by the limits of its rigid form. Literary comparisons are of limited value. One thinks of Dos Passos’ U.S.A.—a far more ambitious undertaking—but there history is encapsulated in separate sections, while here it is embedded in the fabric of the narrative. The real influence is not literary but musical.

…

“It is not by chance that the figure of Houdini keeps recurring. What Doctorow is after is magic; the particular magic he sees, like Joplin’s music, is a form of escape.

Joplin said—and Doctorow quotes as his epigraph—’Do not play this piece fast. It is never right to play Ragtime fast.’ It would not be right to read Ragtime fast.”

–John Brooks, The Chicago Tribune, 1975

*

World’s Fair (1985)

He always counseled daring, in whatever situation, the courage to test the unknown.

“By flaunting the artificial line dividing the true from the imagined, Mr. Doctorow not only suggests in World’s Fair that the process of remembering is by definition a process of invention, he rejects altogether the notion that imagination and memory are ever pure of each other. His purpose in World’s Fair seems to be to create a work that succeeds as oral history, memoir and novel all at once. Unfortunately, these disparate genres don’t always make the best of bedfellows, and until its breathtaking final 100 pages, when it becomes most fully novelistic, Mr. Doctorow’s new novel seems as peculiar a mix of brilliant vision and clumsy self-indulgence as the fair it so artfully describes.

…

“…that, perhaps, is why World’s Fair, as an amalgam of these genres, has a fractured and inconsistent feel to it. Its structure is that of an autobiography, beginning at the beginning and moving through the life of its protagonist with the thoroughness of a catalogue; but where a work of biography derives its imperative from the significance of the life it describes, in a novel, it is the author, not the subject, who must provide the reader with a sense of what to read for; we, as readers, expect from a novel an organizing principle more substantive than chronology, an implicit sense of direction and occasional clues, no matter how vague, that we’re moving toward some revelation. And that is what seems to me to be wrong with World’s Fair; only in its last third, where it becomes most fully novelistic, does this oddly shaped book achieve a sense of purpose and offer the rich rewards readers have come to expect from Mr. Doctorow’s work. Until that point, the reader feels as if he were listening to young Edgar in the park, practicing his ventriloquial drone: a child chattering to himself, and only sometimes achieving the compelling thrown voice of true fiction.”

–David Leavitt, The New York Times, November 10, 1985

*

Billy Bathgate (1989)

When crime was working as it was supposed to it was very dull. Very lucrative and very dull.

“In sentences with nicely clutched transmissions, a long limousine runs, one night in 1935, onto a New York pier, where it smoothly transfers its human cargo to a short tugboat. A boy of fifteen, leaping by impulse onto the boat, is about to undergo the crucial event of his life. He will watch a man die in the muted ritual of one of Dutch Schultz’s ‘necessary business murders.’ The gangster is going to kill one of his own hired killers, Bo Weinberg. Billy, the boy looking down from the boat’s rail, sees ‘a lighted pucker of green angry water.’ Schultz, entering the cabin below him, has turned on its light. Going inside himself, he watches preparations for the murder by ‘the almost-green shards of one work light.’ It is more frightening to be thrown about on a vibrating boat than to lie in the sand at night, like Nick Carraway, thinking of the green light that beckoned Gatsby over the water. Nick, already an adult, meets a Gatsby who has covered up his criminal past. Billy, a streetwise boy but still a boy, meets Dutch Schultz at the height of his lawlessness. Yet Billy is in some ways less dazzled than Nick by the glamour of the man beyond rules.

…

“Doctorow, like Twain, like Dickens, sees adult possibilities in ‘the boy’s book’—the tale of an orphan, not yet socialized into ordinary adult life, who acquires an outlaw mentor. This formula, at its best, combines psychological subtlety (the study of formative experiences undergone in a state of peril), with social criticism (the ‘normal’ looks odd if not crazy when seen from outside). Thus Billy, outside accepted moral systems, must create his own code of responsibility, as Huck does.

…

“This is Doctorow’s first superbly constructed novel. The first-person narrator reassembles boyhood impressions, moving back and forth over the year of his gang activity with easy recall yet with an adult’s remembering vocabulary. The tone is consistent, convincing despite a lingering tendency to the precious—adverbs like ‘workingly,’ wordplays like ‘culled cash, or cold cash, and then it turned into a gold cache.’ Doctorow has previously used an arch third-person narrator (in Ragtime), or a Kerouacian first-person (in Loon Lake). He has not been able to sustain the first-person tone, so he alternates narrators (not only in Loon Lake but in World’s Fair). Even in The Book of Daniel, the first-person narration was interrupted by dissertation notes and other intrusive gimmicks. But here the story flows; the dialogue is mainly filtered through the narrator’s memory, continuous with everything else recalled; sentences glide on for a page and a half at a time with no sense of effort. The prose is itself charged with the ‘three-dimensionality of danger’ Billy finds in Dutch Schultz’s presence.”

–Garry Wills, The New York Review of Books, March 2, 1989

*

The March (2005)

It was as if God had decreed this characterless engagement of brainless forces as his answer to the human presumption.

“A many-faceted recounting of General William Tecumseh Sherman’s famous, and in some quarters still infamous, march of sixty-two thousand Union soldiers, in 1864-65, through Georgia and then the Carolinas, it combines the author’s saturnine strengths with an elegiac compassion and prose of a glittering, swift-moving economy. The novel shares with Ragtime a texture of terse episodes and dialogue shorn, in avant-garde fashion, of quotation marks, but has little of the older book’s distancing jazz, its impudent, mocking shuffle of facts; it celebrates its epic war with the stirring music of a brass marching band heard from afar, then loud and up close, and finally receding over the horizon. Reading historical fiction, we often itch, our curiosity piqued, to consult a book of straight history, to get to the facts without the fiction. But The March stimulates little such itch; it offers an illumination, fitful and flickering, of a historic upheaval that only fiction could provide. Doctorow here appears not so much a reconstructor of history as a visionary who seeks in time past occasions for poetry.

…

“The March carries us through a multitude of moments of wonder and pity, terror and comedy, to the triumph of Southern surrender and the sudden tragedy of Lincoln’s assassination. Sherman’s march is large enough, American myth enough, to pull even a laggard recruit along, and to hold Doctorow’s busy imagination fast to the reality of history even as he refreshes our memory of it.”

–John Updike, The New Yorker, September 12, 2005