“If adultery kept many novels ticking over during the 19th century, then drugs are doing the same nowadays. To rephrase William Empson, drug abuse, not death, is now the trigger of the literary man’s biggest gun. But the static charge that built up before people started really writing about drugs has diminished: there is no room for amateurs now.

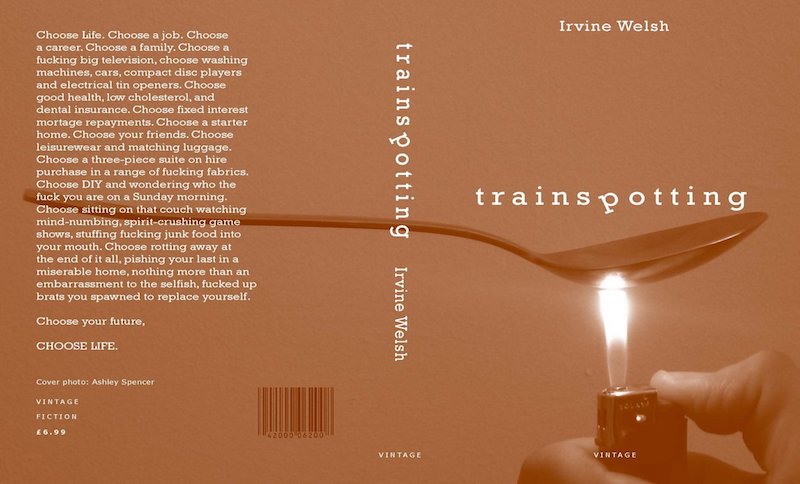

The professionals are, of course, the junkies. The past year or so has seen some scarily accurate heroin novels by people who have, in one way or another, done their homework. Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting is about the life of a group of Edinburgh heroin addicts, with the odd alcoholic and psycho thrown in. The whole is written in phonetically reproduced Edinburgh dialect (‘Ma heid’s gaun doon. It jerks up so suddenly and violently, ah feel it’s gaunnae fly oaf ma shoulders ontae the lap of the testy auld boot in front ay us.’) There is a plot, but you could be forgiven if you missed it, and the novel’s topos is — apart from the odd shot of bleak comedy — unforgivingly grim. Yet it’s a page-turner, and not just because Welsh seems to know exactly what he’s talking about.

The pre-publicity about Trainspotting emphasises its rawness, and it’s true that the scene where the main narrator retrieves two opium suppositories after a burst of withdrawal-induced diarrhoea is extremely revolting; but then if you’re a junky this kind of thing must happen all the time. The real nastiness of the book, or the aspect that should make most people uncomfortable, is its depiction of the gulf that exists between the working class and most of the people reading this newspaper. Trainspotting gives the lie to any cosy notions of a classless society.

The despair at the heart of this book is predicated on violence: whether between Hibs and Hearts fans, Catholics and Orangemen, or two groups of drinkers in a pub. One character, Begbie, can barely stand not hurting someone for five minutes at a stretch. Having kicked his pregnant girlfriend in the crotch (for being ‘lippy’ — asking him where he’s going), he muses later in the pub: ‘That cunt’s deid if she’s made us hurt that fuckin’ bairn.’ Welsh does a sickening, brilliant job of getting inside Begbie’s head. Otherwise, he doesn’t advertise his prose style (which is finely enough tuned to differentiate between amphetamine- and ecstasy-induced gabblings). What informs the book is rage that such things should happen. People who want to find out why and how they happen as they do should start here.”

–Nicholas Lezard, The Independent, August 28, 1993

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.