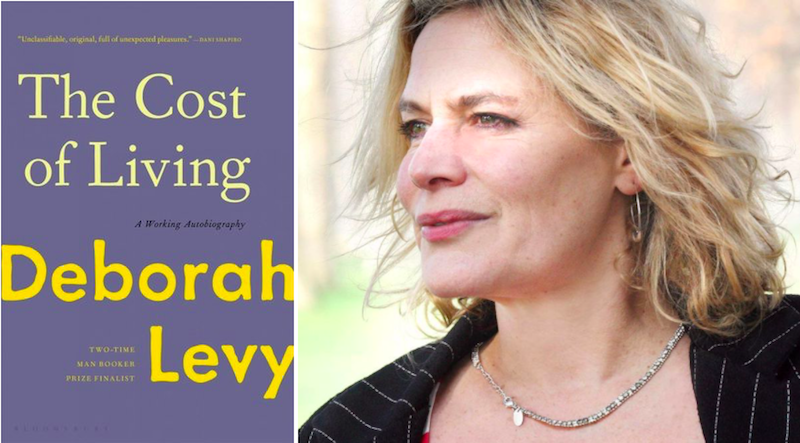

Deborah Levy’s The Cost of Living is published this week. She shared her list of five books that unsettle boundaries with Jane Ciabattari.

*

Your Silence Will Not Protect You, Audre Lorde

Silver Press is a very selective, young feminist publishing house based in London. They had the genius idea of collecting Lorde’s lucid, angry, generous essays and poems in one volume and publishing them together for the first time in the UK. Lorde’s uncompromising message resonates today—“My silences had not protected me. Your silence will not protect you.”

Jane Ciabattari: Indeed the title and her message could certainly stand as a motto for our times. How do you think literature will continue to shift—bringing back earlier voices, publishing voices we might not have heard—as the current moment extends?

Deborah Levy: When a writer strikes on something true and bold, she can smell the smoke, and so can her readers—past and present.

The Hearing Trumpet, Leonora Carrington

I have always loved the imaginative reach of the paintings and writing of this very English provocateur—though Carrington lived for decades in Mexico City. She took many risks in her life and in her art. The Hearing Trumpet is the bizarre story of elderly Marian Leatherby who, with her ornate hearing trumpet, can hear the whispered, sinister conspiracies of her family. Carrington invented her own reality, which is probably the point of art.

JC: I love Carrington’s fiction, and her art. Is there an image from her work you associate with this story?

DL: I often think about Carrington’s dreamlike Self-Portrait (1937-8), mostly because this painting has immense authority, a complete conviction of ideas and ambience. The wild white horse in the exterior of the framed window and the white rocking horse floating above her head, seem to be in conversation with each other—and of course, Carrington’s alter ego is that female hyena. It features in her surreal short story, “The Debutante.”

Picasso by Gertrude Stein

Stein is a writer who broke so many boundaries that it’s hard not to be baffled by her every sentence. I have long admired her hilarious and playful dance with language. I consider her essay on Picasso (they were pals in Paris where he painted her portrait in 1906) one of the most insightful explorations of the sensibility of an artist I have read to this day.

JC: Do you share her impulse to break boundaries? And how do you examine your own sensibility through this lens?

DL: No, I don’t break boundaries in the linguistic ways that Stein so relished. Above all, she wanted to put her long psychology training at Radcliffe College under the tutorship of William James (brother of Henry) to work. So, she was interested in streams of unbroken consciousness and cadence at the cost of everything else and the multiple view points of cubism. A Stein-shaped sentence is a very bespoke thing—you need an espresso martini to recover. What I share with her, though, is a belief that in art, the sky is not always blue and the grass, alas, is not always green: it’s how we see the sky and the grass that makes something new—which is why she was such an astute collector of the modern art that lit up the twentieth century.

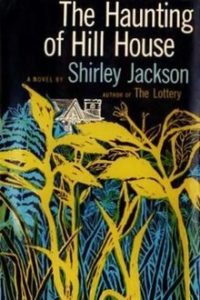

The Haunting of Hill House, Shirley Jackson

This weird psychological thriller about fear is one of the ground-breaking ghost stories of the twentieth century. I admire the skill of Jackson’s plotting, the sly ways in which she creates suspense, and her deceptively plain but always compelling writing. Here’s an example: “I have told lies and made a fool of myself, and the very air tastes like wine.”

JC: While an associate faculty member at Bennington’s low-residency MFA program, I had a chance to explore the model for Hill House—the spacious grey stone building in North Bennington where Shirley Jackson lived with her husband, Stanley Edgar Hyman. I could sense the rage and misery within its walls, and that opening sentence: “Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more.” She is such a master at setting up that horror-infused slant in a story. How does she do it?

DL: Jackson psychologises buildings and inanimate objects and plants and light—they are her avatars with which to explore human flaws, compulsions and desires.

And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos, John Berger

This blew me away when I was in my twenties. At the time it was an unclassifiable book—a collection of thought drifts on themes such as the meaning of home to early human beings, the experience of glimpsing lilacs in the mountains at dusk, the transcendent paintings of Caravaggio. Berger helped me understand that writers are only as interesting as how they think.

JC: When did you first express that narrative approach in your own work?

DL There are many narrative approaches to my own work. In my recent novels, Hot Milk and Swimming Home, I play with surface and depth and the uncanny. I regard the novel as a good home for the reach of the human mind, which can after all go anywhere. So a novel that tames this kind of reach is not really working with complexity and coherence, which I regard as twins in the writing game. One of the twins has a long neat plait, the other has not brushed her hair. In my nonfiction, digressions and thought drifts are part of the narrative design. To write our life as we feel it is a freedom we mostly do not take, but I get somewhere near that strange place in The Cost of Living.