Happiness is only real when shared

*

“The strangely fascinating hero of Jon Krakauer’s strangely fascinating book Into the Wild is a young man who starved to death in the Alaskan wilderness in the summer of 1992. That is the starting point of a narrative that seeks to find out why we should care.

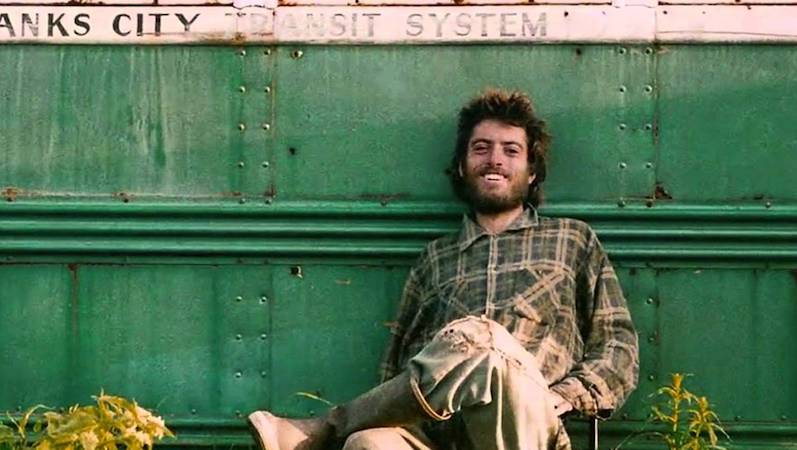

An electrician who had picked him up four miles out of Fairbanks pressed a pair of rubber boots and two sandwiches on the dangerously underequipped but charming hitchhiker, who would vouchsafe no name but Alex. His parents had named him Christopher McCandless, but in his travels he preferred the invented identity Alexander Supertramp. Alex shouldered his backpack—containing little more than books and rice—and his .22-caliber rifle and walked into the forest, to live off the land or die trying. It was April, still winter in Alaska.

Coming upon the impassable Toklat River, he gave up the idea of walking the 300 miles from Mount McKinley to the Bering Sea, Mr. Krakauer writes, and took up residence in a rusting Fairbanks city bus that had been fitted out as a crude shelter. He then entered on what he called, in a manifesto scrawled on a piece of plywood, ‘the climactic battle to kill the false being within.’

Somehow McCandless grubbed a living from the snows—gathering last year’s rose hips and wizened berries, shooting squirrels, ptarmigans, porcupines and finally, in June, with his puny little .22, a moose. He tried to smoke the meat, but his moose quickly spoiled.

By late summer, McCandless’s incompetence and overconfidence had caught up with him. The hunters who found his rotting corpse in September also found this note:

‘S O S. I need your help. I am injured, near death and too weak to hike out of here. I am all alone, this is no joke. In the name of God, please remain to save me. I am out collecting berries close by and shall return this evening. Thank you, Chris McCandless. August?’

Dying at the age of 24, he had resumed his real name.

“What was with this guy? Why should we care if he had no better sense than this? (The reactions of most Alaskans who read about his death ranged from annoyance to indignation.) And what ‘false being’? He kept journals, and in between silences would jabber out his ‘philosophy’ for hours, but the Supertramp’s ideas are never lucid enough to give us a clue.

And yet, as Mr. Krakauer picks through the adventures and sorrows of Chris McCandless’s brief life, the story becomes painfully moving. Mr. Krakauer’s elegantly constructed narrative takes us from the ghoulish moment of the hunters’ discovery back through McCandless’s childhood, the gregarious effusions and icy withdrawals that characterized his coming of age, and, in meticulous detail, the two years of restless roaming that led him to Alaska. The more we learn about him, the more mysterious McCandless becomes, and the more intriguing.

Wherever he went, McCandless sought out the detritus of the society of privilege whose child he was—the son of accomplished, prosperous parents (his father was an outstanding scientist with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration). McCandless detested the world of accomplishment and prosperity. When he graduated from Emory University (with a grade point average not far short of a perfect 4), he gave his inheritance of more than $24,000 to charity and, without a word to anyone, hit the road. What is fantasy in a Tom Waits song was McCandless’s notion of the good life.

If the world no longer offered the sort of wilderness that freely killed those who braved its dangers, then McCandless would create a wilderness within, discarding the rudimentary protections of modern life—matches, maps, even warm clothing. ‘In his own mind, if nowhere else, the terra would thereby remain incognita,’ Mr. Krakauer writes. Hardly eating, never letting his anguished family know where he was, nearly dying of thirst in the Mojave Desert, canoeing a storm-racked Gulf of California, setting fire to the last of his money, he vowed, as he wrote to an acquaintance, ‘to live this life for some time to come. The freedom and simple beauty of it is just too good to pass up.’

“Mr. Krakauer, a contributing editor at Outside magazine, tracks down virtually everyone who knew McCandless in his two years of wandering. As their memories reconstruct Alexander Supertramp, an image of the young anchorite begins to emerge, so vivid at times that it dazzles, at others so mystifying that one wants to scream. The people who meet him love him, while the reader longs to kick him in the pants. An 81-year-old man whom Mr. Krakauer calls Ronald A. Franz loved McCandless so much he begged to adopt him as a grandson.

‘We’ll talk about it when I get back from Alaska, Ron,’ McCandless replied. The author adds: ‘He had again evaded the impending threat of human intimacy.’

After he had slipped away, McCandless wrote Franz an insolent letter admonishing him to live as he, the Supertramp, saw fit: ‘If you want to get more out of life, Ron, you must lose your inclination for monotonous security and adopt a helter-skelter style of life that will at first appear to you to be crazy.’

‘Astoundingly,’ Mr. Krakauer writes, ‘the 81-year-old man took the brash 24-year-old vagabond’s advice to heart. Franz placed his furniture and most of his other possessions in a storage locker, bought a GMC Duravan and . . . sat out in the desert, day after day after day, awaiting his young friend’s return.’

“McCandless’s passion was all for the struggle within himself, a half-blind inner seeking for he knew not what—some sort of transcendence through renunciation. The reader never comes to make sense of his spiritual craving, but its very impalpability makes it familiar. Do we not all thirst for something we cannot define? Does McCandless’s fanatical determination to find it make him a saint, a holy fool or just plain nuts?

The one weakness of Mr. Krakauer’s attempt to understand Chris McCandless lies in an inadequate consideration of psychiatric illness. Indeed, he says straight out, ‘McCandless wasn’t mentally ill.’ But in a long and engaging aside about his own youthful daring of death, Mr. Krakauer lets us know that he himself has sought out risks that most of us would call insane.

Did McCandless want to die in Alaska? That is Mr. Krakauer’s ultimate question, and the whole book can be seen as a quest for a compassionate answer. Mr. Krakauer’s antihero conforms to no familiar type. His contradictions, in retrospect, do not illumine but rather obscure his character. In death, he passes beyond the reach of mortal comprehension.

Christopher McCandless’s life and his death may have been meaningless, absurd, even reprehensible, but by the end of Into the Wild, you care for him deeply.”

–Thomas McNamee, The New York Times, March 3, 1996