Dead men are heavier than broken hearts.

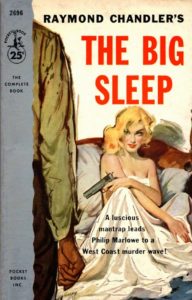

“Most of the characters in this story are tough, many of them are nasty and some of them are both. Philip Marlowe, the private detective who is both the narrator and the chief character, is hard: he has to be hard to cope with the slimy racketeers who are preying on the Sternwood family. Nor do the Sternwoods themselves, particularly the two daughters, respond to gentle treatment. Spoiled is much too mild a term to describe these two young women. Marlowe is working for $25 a day and expenses and he earns every cent of it. Indeed, because of his loyalty to his employer, he passes up golden opportunities to make much more. Before the story is done Marlowe just misses being an eyewitness to two murders and by an even narrower margin misses being a victim. The language used in this book is often vile, at times so filthy that the publishers have been compelled to resort to the dash, a device seldom employed in these unsqueamish days. As a study in depravity, the story is excellent, with Marlowe standing out as almost the only fundamentally decent person in it.”

–Isaac Anderson, The New York Times, February 12, 1939

*

It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained-glass window.

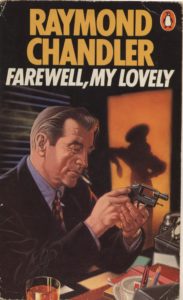

“This is a tough one: superlatively tough, alcoholic, and, for all its wisecracks, ugly rather than humorous. Like many ‘swift-moving’ tales, it is sometimes confusing in its rapid succession of incidents which may or may not have an integral connection with the plot. And the actual mystery is not important. It isn’t so difficult to guess what had become of the beautiful cabaret singer Velma. The identity of the unpleasing Lindsay Marriott’s slayer has no pressing interest. The murder casually committed by that elemental giant Moose Malloy is only an episode to start the story going. No, the appeal of Farewell, My Lovely is in its toughness, which is extremely well done.

Jeanne Florian may know something or nothing about Velma, but Philip Marlowe’s questioning of that gin-soaked old woman makes as sordid a bet as you’re likely to be looking for. Beautiful Mrs. Grayle has a real place in the story, but it’s the sense of evil all about her that gives you goose-flesh. And Amthor the ‘psychic consultant’ and Sonderberg the ‘dope doctor’ are lesser figures in a novel in which no detail is left undescribed.

But the story’s ever-present theme is police corruption, seen in a murky variety. And several kinds of dreadfulness are handled with a grisly skill.”

–Isaac Anderson, The New York Times, November 17, 1940

*

The French have a phrase for it. The bastards have a phrase for everything and they are always right. To say goodbye is to die a little.

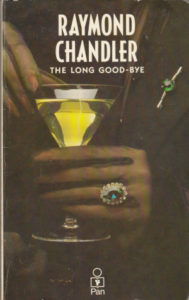

“Raymond Chandler, generally acknowledged as the foremost creator of hard-boiled detective stories after Dashiell Hammett, has written regrettably little of late. After a large number of first- rate novelettes in the Nineteen Thirties and four distinguished novels, 1939-43, he has produced only two novels in the past eleven years. The first of these, The Little Sister (1949), I found badly disappointing though some critics rated it high among Chandler items: but the newest, The Long Goodbye, (Houghton Mifflin, $3), more than assuages the disappointment and makes one wish that Chandlers were as frequent as Gardners.

This one is rather off the hard-beaten path of Chandler-tana. It’s about private detective Philip Marlowe, of course, as are all Chandler novels, but both Marlowe and his creator seem to have mellowed somewhat in fifteen years. The plot deals relatively little with the professional criminal classes, but rather with the tensions—emotional, psychological and fundamental of the upper middle class.

On the whole, despite occasional outbursts of violence, it’s a moody, brooding book, in which Marlowe is less a detective than a disturbed man of 42 on a quest for some evidence of truth and humanity. The dialogue is as vividly overheated as ever, the plot is clearly constructed and surprisingly resolved, and the book is rich in many sharp glimpses of minor characters and scenes. Perhaps the longest private-eye novel ever written (over 125,000 words!). It is also one of the best—and may well attract readers who normally shun even the leaders in the field.”

–Anthony Boucher, The New York Times, April 25, 1954

*