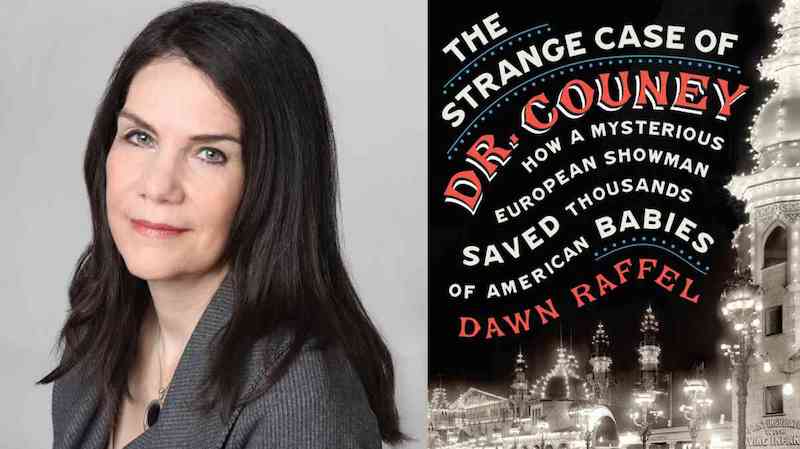

Dawn Raffel’s new book, The Strange Case of Dr. Couney, is published this month. She shared her list of five fantastic snapshots of the national psyche, great reads that capture the giddy essence of world’s fairs, midways and grand expositions, with Jane Ciabattari.

*

The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America, Erik Larson

This nonfiction blockbuster is set at the Chicago world’s fair of 1893. Larson brilliantly intertwines the story of the landmark fair’s creation with the gruesome tale of a serial killer. It’s both an edge-of-your chair thriller and an engrossing investigation of a pivotal moment when the U.S. began to claim its place on the world stage.

Jane Ciabattari: Chicago’s “White City” was built by world-class architects like Frederick Law Olmsted, Charles McKim, Louis Sullivan; included the first ever Ferris Wheel, designed to compete with the relatively new Eiffel Tower; introduced Cracker Jacks and Shredded Wheat, and became the sinister backdrop for a serial murderer who lured women to their deaths in a hotel at the fair. Do you think extremes are part of the atmosphere of world’s fairs?

Dawn Raffel: Happily, I don’t know of any other world’s fairs that included a serial killer—although President William McKinley was fatally shot at the Buffalo World’s Fair in 1901. But I do think these expositions magnified both our noblest and basest impulses. They were a marriage of high culture and bawdy, base-of-the spine entertainment. Fairgoers would happily wander from exhibitions of life-changing new technologies such as the X-ray machine, to lifted-pinkie displays of world-class artwork, and then on to the midway, where they could guzzle the newly invented Dr. Pepper and ogle the hootchy-kootchy dancers.

The Swan Gondola, Timothy Schaffert

Schaffert’s irresistible novel is set at Omaha’s 1898 world’s fair (where Martin Couney made his stateside debut). This magic-infused love story is bursting with showbiz shenanigans and séances, as dusty, Wild West Omaha strives to match Chicago’s gritty grandeur.

JC: A once tattered prairie town is transformed into a Victorian-age wonder, but only for a time. Toward the end, Schaffert writes, “The swan gondola, its long neck broken, would sit shipwrecked at the bottom of the dry lagoon, the fossils of leaves speckling the winged hull. The fairgrounds deserved to become a sad, battered monument to every lost thing of beauty.” World fairs end, and then the temporary glories fade. Do any of the attractions remain?

DR: Only a few. The Eiffel Tower was created for Paris’s Exposition Universelle of 1889. You can still see the 1939 Perisphere at New York’s Flushing Meadows. I’d say the most interesting is Benito Mussolini’s gift to the city of Chicago, on the occasion of its 1933-34 Century of Progress world’s fair. In 1934, the dictator gifted the city an engraved Roman column, in thanks for the warm welcome extended the previous summer to his wingman Italo Balbo, who’d arrived with twenty-four Italian seaplanes in a show of Fascist power. You can find the column in Grant Park.

The Hatbox Baby, Carrie Brown

Chicago’s second, less famous world’s fair took place at the bottom of the Depression (1933-34) and was optimistically called a Century of Progress. Carrie Brown’s immersive novel is set here, featuring fictionalized versions of the incubator sideshow and the notorious burlesque next door. Brown embeds a moving story in a wonderful portrayal of the era.

JC: The hatbox baby was a preemie taken by his father in a hatbox to a fictional doctor who created the Infantorium, a sanitary preemie ward set up at this world fair to bring awareness to the possibilities of saving premature newborns. Your nonfiction book explores the world of Dr. Couney, and how he saved thousands of American babies. Why did he end up doing his work in carnival-esque settings, not in hospitals?

DR: The truth was, Martin Couney had no medical credentials. He knew how to save these babies, and he was decades ahead of the medical establishment. But with no license or formal training, he could not practice in a hospital, nor could he publish in peer-reviewed journals. I find him all the more heroic for that.

World’s Fair, E.L. Doctorow

It’s easy to see why this novel won the National Book Award when it was published in 1985. New York’s first world’s fair opened in 1939, as the world teetered on the brink of war and the Depression hadn’t yet ended. Doctorow’s story of a schoolboy coming of age against the backdrop of the grand exposition is both a memorable personal story and an indelible time capsule.

JC: I can’t count the number of times I’ve driven past the old World’s Fair site at Flushing Meadows and wondered how it felt to see it! Doctorow gives us that feeling in the last third of this autobiographical novel, when young Edgar visits the fair and is transported: “As the evening wore on I forgot everything but the World’s Fair. I forgot everything that wasn’t the Fair as if the Fair was all there was, as if going on rides and seeing the sights, with crowds of people around you and music in your head, were natural life. I didn’t think of my mother or my father or my brother, or of school or the Bronx or even of keeping my wits about me and watching my step.” He’s escaping the harsh facts of the world outside. How did Doctorow best use the World’s Fair to capture such a vivid snapshot of the Depression era?

DR: Every world’s fair was a grand display of optimism, no matter the circumstances of everyday life. They were valentines to the future, which is especially poignant when juxtaposed with a Depression-era coming of age story. People survived by escaping to the movies—one of the few Depression-proof industries—and by believing that better times were coming soon. Doctorow’s novel is all the more moving because we know that what was coming in the immediate future was WWII. (As a little aside, his character Edgar briefly visits the incubators and sees a baby “all hooked up to things.” It’s a tiny anachronism—Couney didn’t have any IVs or monitors.)

Good Old Coney Island: A Sentimental Journey into the Past, Edo McCullough

Coney Island wasn’t a world’s fair, of course—more like America’s id on a bender. (Freud himself visited in 1909 and reportedly said it was the only thing in America that interested him.) The author had Coney Island in his veins: His uncle George C. Tilyou was the legendary owner of Steeplechase Park and his father, James McCullough, ran a dozen shooting galleries. This classic remembrance, first published in 1957 and reissued in 2000, is written with such verve and affection that you feel as if you are there.

JC: “America’s id on a bender,” perfect! McCullough’ subtitled his book, “The Most Rambunctious, Scandalous, Rapscallion, Splendiferous, Pugnacious, Spectacular, Illustrious, Prodigious, Frolicsome Island on Earth.” How much time did you spend at Coney Island, and how did it shape The Strange Case of Dr. Couney?

DR: I made several trips to the Coney Island of today, including the fabulous Coney Island Museum—which might be the most fun you’ll ever have in a museum—and the annual Mermaid Parade, which everyone should experience at least once in their lifetime. I also immersed myself in histories of Coney Island in its trippy heyday. I tried my best to capture its inimitable flavor. It’s really like no place else on earth.