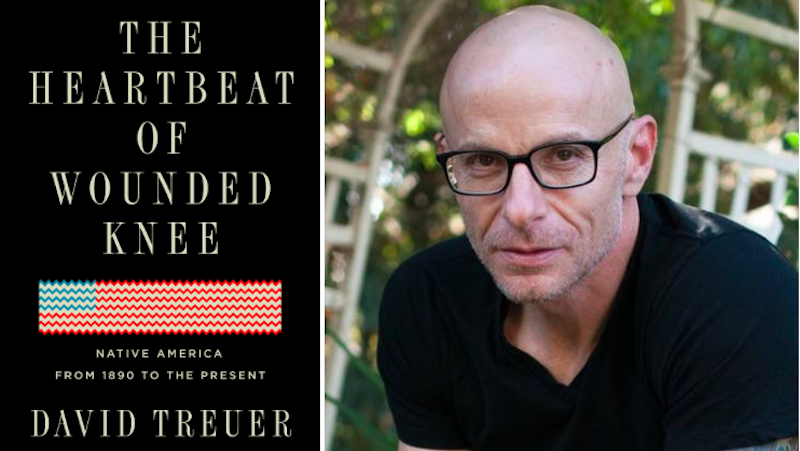

The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America by Andrés Reséndez

This book is a game changer. It reminds us that the slavery of the indigenous people of North America predated and outlasted (by hundreds of years) the institution of African slavery in the New World. And, more shockingly, that even after Indian slavery was declared illegal, it lived on in other forms and in other names. Not only that: it also mounts a serious challenge to the idea that the death of millions of North American Indians was solely or even mostly due to disease; arguing instead that disease was aided and abetted by slavery itself.

Jane Ciabattari: Reséndez illuminates such practices as the enslavement of Navajos and other western tribes in the 1860s, during and after the Civil War. And his focus on the “other slavery”—forced labor that lived on after Indian slavery was illegal, including the selling of convict labor and debt peonage—is also likely news to many readers, as is the fact that Native Americans only legally became citizens in 1924. What do you consider Reséndez’s most enduring contribution in this book?

David Treuer: The most enduring contribution of Reséndez’s book is twofold: 1) The way he makes us radically rethink everything we thought we knew about our collective early history and, even more important, 2) In the last part of his book he suggests forcefully and factually that slavery still exists under other guises. Sex trafficking, excessive fines, and jail time levied against the very poorest of our citizens across the country for minor offenses, are all systems of racial inequality that leave millions of vulnerable people—many of them brown, many of them from Mexico and Central America—with no choice but to flee and work illegally and at a discount in American meat-packing plants, in the fields, picking fruit, and so on.

Masters of Empire: Great Lakes Indians and the Making of America by Michael A. McDonnell

This book is beyond brilliant. MacDonald shows us that America was not made from East to West but that—for over 300 years—the center of the New World was Sault Ste. Marie. From there Indian empires grew, and shaped the politics of North America. MacDonald also shows us that rather than being subsumed by waves of European powers followed by the long twilight of America herself, Native nations shaped and were in turn shaped by those powers. There would be no America without Native people.

JC: McDonnell gives us a clear look at the Anishinaabeg dominance in the Great Lakes region during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, their nautical skills, their role as adept traders—including facilitators of trade with Europe. Which of his points do you find most surprising?

DT: LOL. All of it. I always knew my tribe had a long history and lasting legacy as negotiators, politicians, and players of deep politics, but I had no idea for how long, and how far, and how effectively!

Violence Over the Land by Ned Blackhawk.

Blackhawk’s masterpiece illustrates how enmeshed Indian lives have been in the making of the American nation and American character. A strong reminder that the values, thoughts, and actions of Indian actors were not merely responsive, they were generative. Blackhawk reminds us that Indians made history as much as those who would try (and fail) to do away with us.

JC: Blackhawk gives us two centuries of Early American history that emphasize the experience of the Ute, Paiute, and Shoshone Indians during the westward expansion, emphasizing the role of violence in remaking “much of the continent before U.S. expansion.” His accounts of the Bear River Massacre of January 1863 in which hundreds of Shoshone were killed, and of the 1911 massacre of a Shoshone family are particularly vivid. His last chapter takes a personal turn, when he writes of his grandmother, and of the family’s evolution as non-reservation Indians. Would you call Blackhawk’s family history unusual?

DT: Not at all. Blackhawk reminds us of the enduring legacy of American violence and the ways it has left its mark on all of us, and he reminds us of the resilience and diversity that are obvious to most Natives but usually go unnoticed by outsiders.

Legacy of Conquest by Patricia Nelson Limerick

MacArthur Genius Grant writer and academic Patty Limerick’s groundbreaking work (first published in 1987 but more relevant than ever thirty years later) bears reading by everyone. She digs under the myths of the American West (gunslingers and sheriffs and Indians and outlaws) and shows us that western expansion and conquest was a business and had at its core economic industry. Limerick’s insights are not only applicable to the past, they are important now. The pipeline protest at Standing Rock in 2015-2016 seemed like an ideological struggle between good and evil, natives and the (white) government, and maybe it was, but it is also an economic concern that pits soulless industry against the common good.

JC: Limerick argues that as slavery is the narrative underpinning of the history of the South, conquest is to the history of the West. And she demonstrates the economic motivation for much of the westward expansion. She also makes a point particularly pertinent when considering the history of Native America: “One skill essential to the writing of Western American history is a capacity to deal with multiple points of view.” To what extent did that capacity to deal with multiple points of view inform your new book?

DT: I can only aspire to be as comprehensive, as thorough, and as detailed as Limerick. But I have tried to show—in the structure, sense, and subject—the ways in which Indian lives aren’t one-dimensional, or only relevant in terms of America’s excesses and its sins. To do that I needed to look at Indian lives from the perspectives of my people, from the vantage of history, and from—for lack of a better phrase—the snug of my own soul, my own life. I can only hope I’ve communicated a fraction of the diversity and depth, texture and deep present-tense, and the many (often painful and yet often glorious) layers of our shared indigenous modern existence.

The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon

Everyone should read this book and bear witness to the ways in which inequality and racism and imperialism take a psychological toll on individuals at the far end of policy and structural inequality. Although Fanon is from the French Caribbean and is writing primarily about North Africa, his vision of the effects of subjugation is worth remembering for us all.

JC: Fanon writes, “Decolonization, which sets out to change the order of the world, is clearly an agenda for total disorder. But it cannot be accomplished by the wave of a magic wand, a natural cataclysm, or a gentleman’s agreement. Decolonization, we know, is an historical process: In other words, it can only be understood, it can only find its significance and become self-coherent insofar as we can discern the history-making movement which gives it form and substance.” At what point do you see the status of the decolonization of Native America (given that Native America is not monolithic, but rather encompasses hundreds of tribes)?

DT: Fanon was writing about the psychology of colonialism, what it does to the minds and hearts of the people who suffer under its yoke and from its effects, and he makes a simple and logical and informed claim: Since colonialism is violent, it creates violence in us, and it is natural to expect that often our efforts to undo it will be chaotic and violent and complicated. He also gives voice to the rage we feel when we continue to endure in unjust societies. But at what stage is Native America? That’s impossible to answer. We have people being arrested for protesting ongoing efforts to create yet more pipelines across the heartland the very same week the first American Indian women were sworn into Congress and Peggy Flanagan—Ojibwe from Minnesota—was sworn in as the highest ranking American Indian in executive office as Lieutenant Governor of Minnesota. These protests are also ongoing during the government shutdown, which radically impacts the services and support our tribal nations can offer their citizens (public safety, healthcare, etc.) because so much of our funding comes from and through federal agencies that are shuttered. So where are we at? We are where we’ve always been (and which I try to show in my book): We are everywhere, we are doing everything, and through it all we continue to remind everyone that the practices and policies of government matter, that the attitudes and efforts of our neighbors matter, and that we must, all of us, continue to fight to bend America’s course away from its most base impulses and closer toward its stated ideals.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·