Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

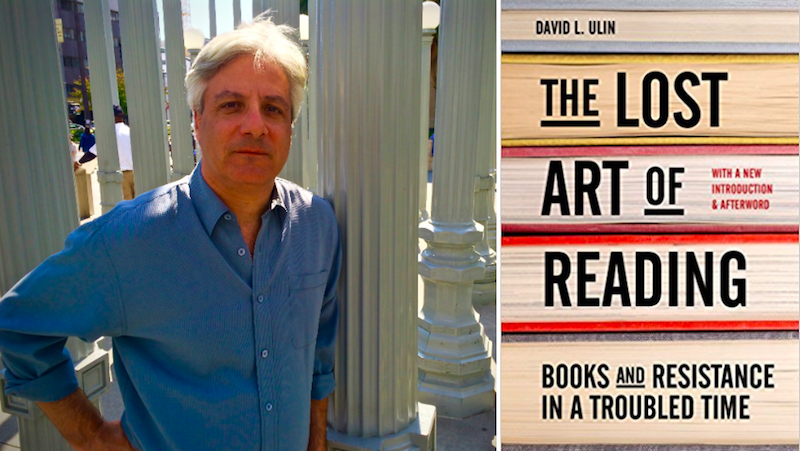

This week we spoke to author, editor and critic, David L. Ulin.

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

David L. Ulin: This is a hard question to answer, since one of the pleasures of reviewing for me has always been that of discovery, and classic books—even though we discover them when we first read them—come to us through the filter, through the scrim, of their classic-ness. That being said, I think I’d want to go back (maybe) and review Tristram Shandy. Laurence Sterne’s great anti-novel, digression upon digression, which Milan Kundera regarded (along with Diderot’s Jacques le Fataliste) as progenitor of a counter-history of the novel, and others have cited as predicting (or at least presaging) the fluidity of the internet. I’m not sure about any of that, but the first time I read it, in college, I knew I was in the presence of something I had never seen before. As an alternate choice, perhaps, Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy. I carry both of these books with me, I have them downloaded on my phone. They are reminders that weirdness, unconventionality, iconoclasm is not contemporary but wholly human, that the books and writers I am looking for are the ones who make it up (as we all must) as they go along.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

DU: I don’t know if it is unheralded exactly, but more people should be reading Megan Hunter’s The End We Start From—a brief, epigrammatic first novel that came out in November, and reframes the fiction of apocalypse, or is that the fiction of motherhood? In actuality it is both. Hunter is a vivid, pithy writer, and her vision of a flooded London, and the resulting chaos, is perhaps most terrifying because it is so plausible. At the same time, she is never satisfied to fall back on easy signifiers, and the most compelling aspect of the book is its resilience, its insistence that, to borrow a line from Beckett, “I can’t go on, I’ll go on.”

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

DU: That criticism is a service industry. It is, of course—on some level, the responsibility of the reviewer is to tell us whether or not to buy the book—but this is also drastically oversimplified. Rather, the critic is responsible to write an essay, to create a discrete piece of writing that can be experienced on its own terms, not to rehash or dismantle the book but to engage with it as we engage with any experience, and then to report back from the territory, as it were. I don’t like plot synopsis and I don’t like reviews where I can’t see the critic thinking, pushing or questioning or doubting, making an aesthetic argument. In the best reviews, the book is just a starting point, which is not an argument for self-indulgence but for its opposite: the deep dive, the conversation on which all literature (and yes, book reviews are a form of literature, or should be) depends.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

DU: I think the core of it hasn’t changed at all. (See my answer to question 3.) It still has to begin and end with engagement, with a kind of openness, or conversational intention, and enthusiasm for the process at hand. At best, social media creates access for criticism, as well as a sense of shared mission, although this can be a double-edged sword, especially when it comes to negative reviews. I think the negative review—or making a space for the negative review—is essential, not for its negativity but because a reviewer must be able to be honest about how a book does or doesn’t work. That being said, any space where we are talking about books is a good thing, and social media has amped connections and community, which are essential for writers and readers, who by necessity connect with each other out of solitude.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

DU: There are many, but two favorites are Parul Sehgal and Dwight Garner at the New York Times. I also admire very much the work of Christine Smallwood, Geoff Dyer, and Zadie Smith, who is, for my money, the most intriguing essayist and critic out there, perhaps because she doesn’t define herself entirely (or even at all) in such terms. For her (as is also true of Dyer), criticism and essay writing are expressive of a larger point-of-view, a social or political or aesthetic stance, a way of standing in the world. There is little separation—at least for me as a reader—between the sensibility of her novels and her essays. All are part of the exploration, the revelation, of the work.

*

David L. Ulin is the author or editor of ten books, including Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles, shortlisted for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay, and the Library of America’s Writing Los Angeles: A Literary Anthology, which won a California Book Award. A 2015 Guggenheim Fellow, he is the former book editor and book critic of the Los Angeles Times, and a contributing editor to Literary Hub. A second edition of his book The Lost Art of Reading will be published in September, with a new introduction and afterword.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.