Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, a new feature in which books journalists from around the US share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recents gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic from a different part of the country, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

This week we spoke to the poet, critic, and essayist David Biespiel.

*

Book Marks: What classic book of poetry would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

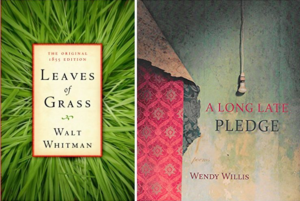

David Biespiel: Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman. Wouldn’t that have been amazing to review the first, 1855 edition? Question is, would one be reviewing Leaves of Grass from a pre-Civil War, presumably abolitionist stance? Or from today’s post-Obama perspective? What does one do with Whitman’s optimism and nationalism—even if you were writing five years before the start of the Civil War? One approach I’ve tried to forge as a poetry critic—not much different from the work I do in my own poems—is, how do you consider a book of poems inside a broader cultural cosmos. I try to be thoughtful beyond what a book of poems is doing word by word, line by line, poem by poem, and—instead of, or in addition to—reckon with its connection to the communal, the public, the inter-mutual. To say nothing of its connection to other books by the same poet or other poets. With Leaves of Grass I suppose you’d have to acknowledge the impact of Jeffersonian democracy as well as Jacksonian democracy on the book. More so than Lincolnian democracy. There’s an argument to be made that Leaves of Grass comes out of the cultural air that became the presidential campaign of 1860. Abraham Lincoln won the general election with under 40% of the vote. If you’d combined the tallies of the Northern Democratic candidate, Stephen Douglass, with the Southern Democratic candidate, John C. Breckinridge, Lincoln would have lost. So much of Leaves of Grass wrestles with those sorts of divides. Among others, these lines would have called for some thoughtful critique:

Urge and urge and urge,

Always the procreant urge of the world.

Out of the dimness opposite equals advance . . . . Always substance and increase,

Always a knit of identity . . . . always distinction . . . . always a breed of life.

To elaborate is no avail . . . . Learned and unlearned feel that it is so.

Sure as the most certain sure . . . . plumb in the uprights, well entretied, braced in the beams,

Stout as a horse, affectionate, haughty, electrical,

I and this mystery here we stand.

BM: What unheralded book of poetry from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

DB: Wendy Willis’s A Long Late Pledge. It’s a book about American mythology, the American West in relation’s to Thomas Jefferson’s conception of the West, and the fragile state of democracy in the early 21st century. Willis is a third wave feminist and former federal public defender who interrogates everything from motherhood to the Bill of Rights, all in a post-Owl Wars era.

BM: How does the approach to poetry criticism differ from, say, fiction? What would you say to those who argue that poetry is such a subjective medium, that it resists a traditional critical approach?

DB: Is it? I think they’re the same, or can be. I take it for granted that poets are in the conversation with the full tapestry of human culture; in conversation with other poems both contemporary and ancient, other literary forms; and with other art forms. It can be helpful, I feel, to review new books of poem with some alternative, non-literary frameworks, say. Instead of the literary scaffold of experimental versus traditional verse, one might use filters from the visual arts: expressionistic versus realist. From music: discordant or improvisational versus harmonic. I’ll add this too—although to say it will be instantly debatable—all poets are humanists. I mean that in the traditional sense of the word, as people (as writers, that is) who frame, in their poems, human matters in the context of good and evil and who focus their poetry on the needs of human experience. Therefore, poetry critics can approach new books of poetry from the standpoint of thoughtfully evaluating them as attempts to dramatize and make metaphor from umpteen aspects of civilization, folk life, daily customs, ways of life, society, knowledge, and mores, plus all the traditional components of the humanities, including history, religion, philosophy, politics, and the other arts.

BM: How has poetry criticism, and the poetry community, changed in the age of social media?

DB: Some things have changed, others have stayed the same, so far as I can tell. I’m not someone invested in Internet cultural criticism. So I’m probably the last person to say. When I first started reviewing poetry in the 1980s, I had to hunt for models and for peers. Most poetry reviewing was done—and is still done—in the little magazines. There’s been no increase, so far as I can tell, in poetry reviewing in the glossy magazines or in the political-cultural magazines, like The Atlantic, The Nation, New Republic, The New Yorker, I guess. 21st century online literary magazines, such as The Rumpus or Los Angeles Review of Books, and others, now not only review poetry regularly but because the pieces are always online, they can be disseminated widely (even perhaps widely than print media, sometimes) through social media. Usually by 1) the journal, 2) the reviewer, and 3) the poet. Not always in the order. It seems to me the rebroadcast of reviews through social media has increased the availability of poetry reviews. I’m a book critic for The American Poetry Review. I write several reviews a year, at least, for them. It’s one of our great, historic magazines. A literary treasure. Usually, it turns out, my pieces aren’t posted online. So you’ve got to read them the old-fashioned way. And that’s fine, too. Have the reviews changed in all this time? I don’t see that. There’s still far too much log-rolling in poetry reviews—for the one reason that poets are also the critics. And the reviews read more or less the same as they did fifty years ago, by and by, at least.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

DB: Well to each their own. How about an even ten? Considering peers: William Logan and David Orr are smart and funny, and tough and serrated; Stephanie Burt’s reviews are so enthusiastic they could convince a fish to come onshore and give breathing air a try; same goes for Dan Chiasson; Christian Wiman has the most capacious mind; Angle Mlinko dares icons to remain so; Daisy Fried has a finger on the poetic moment always; Wendy Willis has sharp radar for new poetry in the context of social and civic relationships; Rigoberto Gonzalez and Jason Guriel are fearless. I could go on. I’ve left people off who I read regularly. Apologies to all y’all. Good critics, all. Same time: When I want to refresh my take on how to read poetry critically, I sometimes re-read Robert Hughes, the art critic. Kind of cross-training.

*

David Biespiel is the author of ten books, most recently The Education of a Young Poet (memoir), A Long High Whistle (essays), The Book of Men and Women (poetry), which was named one of the Best Books of the Year by the Poetry Foundation, and the Everyman’s Library edition of Poems of the American South. A contributor to The New York Times, Washington Post, New Republic, Politico, Slate, Bookforum, and elsewhere, he writes the Poetry Wire column for The Rumpus and is book critic for American Poetry Review. Biespiel is the founder of the Attic Institute of Arts and Letters and a longtime member in the MFA program at Oregon State University, as well as the Rainier Writing Workshop low-residency MFA program.

Previous entires in this series:

Writer, book critic, and host of The Other Stories podcast, Ilana Masad

Freeman’s editor and former NBCC President John Freeman

Editor, columnist, and NBCC board member Kerri Arsenault

The New Republic literary editor Laura Marsh

Heller McAlpin, contributor to Barnes & Noble Review, Washington Post, NPR, LA Times, and others

National Book Critics Circle President Kate Tuttle

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.