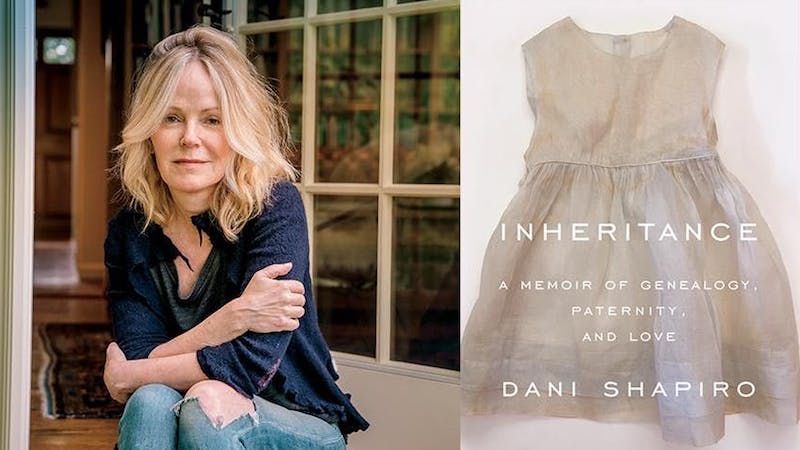

Dani Shapiro’s Inheritance is published this month. She shares five memoirs that take big risks with Jane Ciabattari.

The Suicide Index by Joan Wickersham

The structure of this memoir is a master class in experimental form that actually does something, rather than being simply performative. Virginia Woolf once wrote (in her diaries) that she longed for a device that was not a trick. Wickersham’s structure is precisely that—an index that attempts to order the chaos of a parent’s suicide.

Jane Ciabattari: It’s a brilliant form—entries like “anger about,” “other people’s stories about,” “possible ways to talk to a child about,” “romances of mother in years following.” Do you think the form also allows the containment of the powerful emotions that follow a father’s suicide?

Dani Shapiro: Exactly. It’s the containment—the indexing—that so beautifully allows for such painful internal material to be ordered and made into literature. Anne Sexton once wrote that pain engraves a deeper memory, and yet when it comes to attempting to write memoir about something as shocking and painful as a parent’s suicide, a challenge, I imagine, would be that the vastness and shapelessness of such an event makes it nearly impossible to grasp, much less to articulate, even in time. Wickersham’s index structure also allows room for the reader—breathing room, if you will—white space in which the reader can enter the story, and not be ovewhelmed by it.

The Reenactments by Nick Flynn

This is my favorite of Nick Flynn’s memoirs. An earlier memoir of Flynn’s, Another Bullshit Night in Suck City, is being adapted as a film, and Flynn spends time on the set. So there’s a meta quality to the experience, and the book, as Flynn is present for the reenactment of the suicide of his mother—as played by Julianne Moore—and uses these layers of time, and of reality, cinema, unreality, memory, the expansion and collapsing of time, to great effect.

JC: Flynn’s awareness of time is so powerful. And his sense of what he knows in the future that might comfort himself as a younger man. “Here is the future, tapping my younger self on the shoulder, saying, I will be here for you, if you can find your way to me.” How did you approach the awareness of what you did not know as a younger person in writing your own memoir?

DS: I think his awareness of layers of time why I so respond to Nick’s work. I find it interesting that in my memoir Hourglass, which I wrote just before making a shocking discovery about my own history and identity, was a book in which I was very much aware of reaching out a hand to my younger self. I posed the question: was I already alive in her? Is she still alive in me? There’s that wonderful Didion quote about keeping a notebook: “We are well-advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be…” But then—quite by accident—I found out that the person I used to be, my younger self, hadn’t known the truth of her own identity! The dad who raised me wasn’t my biological father and I had never known it, though much of my life as a writer was an attempt to understand him, to reckon with my family. I now go back to the shelf of my earlier books with utter fascination, and a deep bow to the power of the unconscious, because it’s all there. On some level, I knew. I knew, without ever allowing myself to think it, because the cost was too high, I suppose.

Hunger by Roxane Gay

The form of Hunger, as it circles ever closer around a horrific violent gang rape and it’s psychological and spiritual aftermath, employs white space to great effect. The reader is right there, in that white space, as witness, both compassionate and complicit. I was working on Inheritance when I read Hunger, and it gave me permission to use white space and short chapters, so I’ll always be grateful to this amazing book.

JC: “I think writing always gives us control over the things that we can’t actually control in our lives,” Gay has noted. Did you have that experience while writing Inheritance?

DS: Absolutely. From almost the moment I made my discovery about my dad, I began to take notes. I went out that first morning and bought a stack of index cards and started scribbling—words, images, thoughts, feelings, ideas. I also was very aware that anyone who knew the truth of how I came to be born would be, if still living, very old. I was beset with a sense of urgency. The attempt to find language for what was happening to me consumed me. I have a meditation practice, and some days, while meditating, I would realize that my thoughts had drifted to a place where I was trying to find language. There’s life, and then there’s the page. On the page, we can create coherence, or a semblance of coherence, even if there’s none to be found in our lives. I found myself wondering at times what in the world I would have done with this new information if I wasn’t a writer.

When Women Were Birds by Terry Tempest Williams

Tempest Williams’ mother leaves her all her journals when she dies. They are perfectly lined-up in order, and, Tempest Williams discovers, entirely empty. Faced with shelf after shelf of blank journals, the daughter contends with the mystery of her mother, and the complexity of having a voice herself. Early in the book, after the reader learns of the empty journals, there is a series of blank pages. The first time I turned page after page, I had chills. Talk about a risk! She replicates the strange, ghostly quality of the unwritten for her readers.

JC: Williams describes her mother’s blank journals as “paper tombstones” and “words wafting above the page.” She notes that in Mormon culture, “women are expected to do two things: keep a journal and bear children. Both gestures are a participatory bow to the past and future.” In tracing back her mother’s life, year by year, Williams honors her subversive choice to leave the pages empty. Emptiness, she writes, “translated to longing, that same hunger and thirst, Mother translated to me. I will rewrite this story, create my own story on the pages of my mother’s journals.” Which is more risky, creating her mother’s voice, or her own?

DS: I didn’t read what Williams does here as creating her mother’s voice. The voice is all her own. She’s attempting to piece her mother together, to arrive at a deeper understanding of her by filling the blank page with her own voice. As she writes: “My mother’s journals are capable of receiving my words.” This creates an extraordinary fusion, something I’ve never seen before in the literature of motherhood and daughterhood.

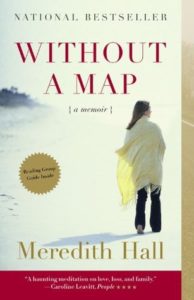

Without a Map by Meredith Hall

Hall was forced to give up a baby for adoption when she was a very young woman, and that absence shaped her entire adult life. The opening chapter to this memoir was written as a stand-alone essay, and establishes Hall’s tone. The word “honest” is overused in describing memoir, but here it really does apply. She is completely trustworthy, heartbreakingly so, as she turns her gaze first on herself, and then on the family and community who shamed and shunned her. It’s no easy thing to write about shame, and she does so with utmost grace.

JC: Hall describes the reaction of her small New Hampshire community when she is discovered be pregnant at sixteen in 1965 and loses family, school, friends, church. “This sort of shunning has the desired effect of erasing a life,” she writes. “Making it invisible, incapable of contaminating.” Is part of her honesty taking on the challenge of understanding why she was shunned?

DS: Actually, I think the shunning—a terrible thing in which her entire community turned its back on her—is part of what Hall grapples with in her story, not so much to understand it, as to understand the lifelong effects of it. The shunning itself was a harsh truth, and not one Hall can ever really metabolize. To me, the memoir’s beating heart lies in the aftereffects of a young woman forced to bear her pregnancy and childbirth in isolation, then give up that child, and told never to speak of it again. She’s exiled from her own self, from her own life, and her journey on the pages of this book is one, ultimately, of reclamation.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·