In reality, there is no such thing as not voting: you either vote by voting, or you vote by staying home and tacitly doubling the value of some Diehard’s vote.

*

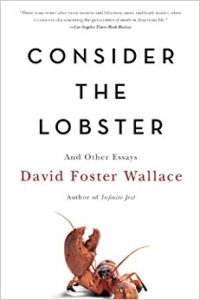

“Reading David Foster Wallace’s new collection of magazine articles, you could be forgiven for thinking that the author of such defiantly experimental fictions as Infinite Jest (1996) and Oblivion (2004) has been an old-fashioned moralist in postmodern disguise all along. The grotesqueries of the 15th annual Adult Video News Awards, which Wallace writes about at considerable length here, present an easy target. And so, to a lesser extent, do the corruptions of English usage in America and the right-wing radio host John Ziegler. But Wallace poses an unsettling challenge to the way many of us live now when, while visiting the Maine Lobster Festival on behalf of Gourmet magazine, he asks if it is ‘all right to boil a sentient creature alive just for our gustatory pleasure.’ His longing for the apparently rare virtues of frankness and sincerity in public life makes him admire John McCain, despite the senator’s ‘scary’ right-wing views.

Turning to literature in essays on Kafka, Dostoyevsky and Updike, Wallace employs a largely moral vocabulary to dismiss such older American novelists as Norman Mailer and Philip Roth as ‘Great Male Narcissists.’ For him, Updike is ‘both chronicler and voice of probably the single most self-absorbed generation since Louis XIV.’ In contrast, he is all praise for Dostoyevsky, largely because the Russian writer’s ‘concern was always what it is to be a human being—that is, how to be an actual person, someone whose life is informed by values and principles, instead of just an especially shrewd kind of self-preserving animal.’

Indeed, reading Dostoyevsky revives Wallace’s old complaint that American writers face an unparalleled difficulty in trying to create a literature informed by ethical values and principles. In an earlier essay titled ‘E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction,’ Wallace claimed that television in its more sophisticated phase had appropriated the ‘rebellious irony’ of the first postmodern writers (Pynchon, Barthelme, Gaddis, Barth), thereby pre-empting and defusing the ‘critical negation’ that was the literary and moral responsibility of his generation of writers. More than a decade later, Wallace remains convinced that ‘many of the novelists of our own place and time look so thematically shallow and lightweight, so morally impoverished, in comparison to Gogol or Dostoyevsky.’

This is strong stuff—Wallace’s blithely assertive manner helps him cover much rhetorical ground very quickly, even if a firmer belief in understatement might have helped him avoid such unhelpful generalizations as ‘our present culture is, both developmentally and historically, adolescent.’ Given such vehemence, it seems fair to point out that compared with the Russian masters, most novelists of any time or place are likely to look shallow and lightweight. And, at their best, the Great Male Narcissists have appeared to possess the ‘degrees of passion, conviction and engagement with deep moral issues’ that for Wallace distinguish the Russians from contemporary American writers.