“You got no fuckin idea how bad it gets. I’m not you. I can’t make it on a couple a high-altitude fucks once or twice a year. You’re too much for me, Ennis, you son of a whoreson bitch. I wish I knew how to quit you.”

-‘Brokeback Mountain’

*

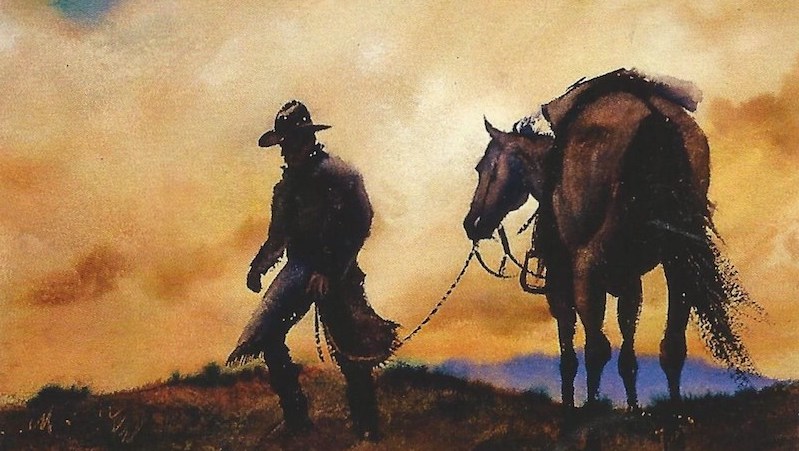

“Here is Annie Proulx mining the ore of language out of a Wyoming rockscape traversed by two itinerant rodeo riders in an ancient truck:

Pake knew a hundred dirt road short cuts, steering them through scabland and slope country . . . over the tawny plain still grooved with pilgrim wagon ruts, into early darkness and the first storm laying down black ice, hard orange dawn, the world smoking, snaking dust devils on bare dirt, heat boiling out of the sun until the paint on the truck hood curled, ragged webs of dry rain that never hit the ground, through small-town traffic and stock on the road, band of horses in morning fog, two redheaded cowboys moving a house that filled the roadway and Pake busting around and into the ditch to get past.

Geography, splendid and terrible, is a tutelary deity to the characters in Close Range: hardpan ranchers, battered cowpokes and bull riders, bar girls and bar brawlers. Their lives are a futile uphill struggle conducted as a downhill, out-of-control tearaway. Proulx writes of them in a prose that is violent and impacted and mastered just at the point where, having gone all the way to the edge, it is about to go over.

“Her writing is gritty and gleaming in this high-country ‘Lower Depths’ (as is Gorky’s in his masterpiece), and in her best-known novel, The Shipping News, set in Newfoundland. Here the background is mountains instead of sea, though in one story, ‘A Lonely Coast,’ there is an uncanny fusing of image. After a series of jealous barroom quarrels, a half-dozen men and women—a waitress, a cook, some ranch hands—pile into a car to drive to another bar 100 miles away. (Distance is place in this infinite West.) As they come down the last grade, the lights of Casper stretch out below:

And if you’ve ever been to the lonely coast, you’ve seen how the shore rock drops off into the black water and how the light on the point is final. Beyond are the old rollers coming on for millions of years. It is like that here at night but instead of the rollers it’s wind.

This may seem like an author’s voice rather than a character’s, but one of Proulx’s talents is to make the distinction irrelevant. She grapples herself to her people with such authentic language that when poetry turns up, the grapple holds and they unforcedly elevate.

The strength of this collection is Proulx’s feeling for place and the shape into which it twists her characters. Wyoming is harsh spaces, unyielding soil, deadly winters, blistering summers and the brute effort of wresting a living out of a land as poor as it is beautiful. Its natives—as distinct from prosperous newcomers—are battered like cannonballs shot from a cannon, as dangerous upon impact and, essentially, as helpless. Character is not fate. Fate is character and landscape is fate. One young man gives up college and goes back to ranch work when his decrepit truck dies and there is no way to cover the distance.

“The violent and the violated inhabit Close Range, often in the same person. Proulx conveys sensibility, but she does it from the outside. Soul is exoskeleton; it works inward from the body and from the world that bruises, fractures and wears the body down to a husk. Bones are a frequent image; a young man whose life will be a series of failed efforts—the highway is moved away from the gas station where he works, a cafe he opens goes broke, beef prices plummet when he gets a small spread—has a face that ‘shows heavy bone.’ His mother inherits ‘a small dogbone ranch.’ In story after story, bones break in falls, car crashes, a frostbite amputation. The very names are bony: Leetil Bewd, Tee Dove, Car Scrope, Flyby Amendinger.

This is splendid material, set out with pain and compassion but above all with a shrewdness of observation that brings the harsh upland life to us in the traditional way that stories are brought: a stranger comes to the door and tells us of a place we do not know. The comfortable America of a rising stock market and a falling awareness of whatever lives outside its concerns cannot even conceive of it. Proulx knows what she could only know not just by living in Wyoming but by the infrared that allows a very few writers clear sight in the dark of the imagination.

She knows, for example, extraordinarily much about males: their bodies (who else writes of them with such lyrical respect?), the roughness and wary companionship of a raw macho society and a sporadic, startling sweetness. When two rodeo riders have a breakdown on the road, another rider stops and tinkers with their engine, all the while holding his infant. ‘I rather have a greasy little girl than a lonesome baby,’ he explains.

“The author’s understanding is at its most remarkable in the astonishing ‘Brokeback Mountain,’ the story of a sudden flare-up of sexual passion between two ranch hands herding 1,000 sheep in summer upland pasture. The passion continues painfully—long separations and rare but explosive consummations—after they marry and for the rest of their lives. It is a story told with equanimity: the sheepherding, the mountains, the strained marriages, the divergent itineraries are not a backdrop but as real as the affair itself. All life is equally and strangely life.

Annie Proulx has only published novels up to now, and in a foreword she tells of uncertainty about the shorter form. In fact, the difficulty with several of the pieces is the opposite of what short-story writers often encounter when they attempt a novel. It is the problem not of sustaining the story but of compressing it. Her material is as richly worked as brocade; like brocade it is hard to trim into too small a swatch.

Her solution in several of the stories is to impose a labored climactic rhythm or a gotcha ending. The result can be garish or melodramatic. ‘A Lonely Coast,’ with its sensitive account of the difficult lives of single women in a rough rural world, tacks on a violent and didactic conclusion. So does ‘People in Hell Just Want a Drink of Water,’ which begins as an engrossing account of a tough ranch family fighting its way to prosperity, then declares the brutality that goes with the success by way of the maiming of a mentally impaired neighbor.

‘Pair a Spurs’ tells of another hard-working rancher, who is driven, in his unconscious starvation for beauty, to an insane passion for a pair of handmade silver spurs and then—comically, grimly—for two women and a man who come successively to own them. Again, there are shrewd details— hardly a story in the collection lacks them—but an abrupt touch of magic realism is only one of several elements strenuously maneuvered for epiphanic shape.

“In two brief stories, gotcha is the point. The best is ‘The Blood Bay,’ a tall tale with a comic reverse, followed by a last line of drawled deadpan. Mark Twain used to do them that way. In another piece, ‘The Half-Skinned Steer,’ the seemingly garish ending works well enough; it is an old man’s dying hallucination, and caps a life story of bitter and futile escape from Wyoming harshness.

It is life stories, in fact, without need of climax, that provide the two prize pieces of this collection. There is ‘Brokeback Mountain,’ but to my mind the finest is the patiently accumulating account of Diamond Felts, a rodeo performer, in ‘The Mud Below.’ He rides bulls, something like riding a tornado. To stay on eight seconds is remarkable; the fall is a twisting horror, halfway between being caught in a spin-dry cycle and pounded by a pile driver.

Diamond has a huge spirit caught in a puny body and mangled by his father’s abandonment, his mother’s lofty contempt and a seeming future of monotonous physical labor. As with Europa, perhaps, the bull is ravishment and godly election as well as destruction. After his first attempt, he bathes in a hot spring, replaying ‘the feeling his life had doubled in size.’ In the years to come—there will not be many—he clings to the memory of this doubling while his maltreated body shrinks and disintegrates.

‘Well,’ says an acquaintance, ‘you rodeo, you’re a rooster on Tuesday, a feather duster on Wednesday.’ On that line Proulx gains the crossroads of great writing, the intersection of the specific and the universal, of the fate offered by her upland Wyoming and by the human condition at large.”

–Richard Eder, The New York Times, May 23, 1999

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.