“To die with dignity does not require company”

*

“In a revealing scene midway through Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, Jon Lee Anderson’s superb biography, Enrique Oltuski, a young Havana-born son of Polish emigrants and an important anti-Communist ally of Che Guevara and Fidel Castro’s, goes into the Escambray mountains, where Che had his headquarters during the latter phases of the struggle against the Batista regime. Che is not in camp when Mr. Oltuski and other members of his party arrive, but as a courtesy, one of Che’s young bodyguards offers Mr. Oltuski some goat meat, which he notices is green with rot. He takes a bite and then has to run outside to spit it out. When Che returns after midnight, Mr. Oltuski watches with ‘horrified fascination’ as Che picks up the goat meat with dirty fingers and eats with apparent relish. The meeting doesn’t go well—Che harangues the urban revolutionaries for what he perceives to be various failings—but on the way back to Havana, one of Mr. Oltuski’s colleagues asks him what he thought of Che. ‘In spite of everything,’ Mr. Oltuski replies, ‘one can’t help admiring him. He knows what he wants better than we do. And he lives entirely for it.’

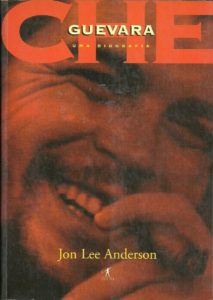

Mr. Anderson, a freelance journalist and the author of an earlier book on guerrillas, spent five years on this volume—the first major biography of Che—and in it he portrays Che as a complex, volatile, ultimately tragic figure who was critical to insuring the victory of the Cuban revolution yet unable to live with the results. This book brings to light a rich collection of diaries and letters—many previously unexamined—and is especially interesting for being written from a largely Cuban perspective. Nearly three of Mr. Anderson’s five years were spent in Havana, where he was able to gain access to important Cuban archives as well as to Che’s famously reclusive widow, Aleida. He also conducted interviews throughout Europe and South America and on three occasions traveled to Russia, where he talked to figures who were crucial in establishing the Kremlin’s policies toward Cuba and the United States.

“From the Russian interviews we learn that the Soviets did not at first take the Cuban revolution seriously, since a rural-based guerrilla-led insurrection was simply not in their playbook. We also learn that they had quite different outlooks on Che and on Fidel. To the Soviets, Fidel was a liberal bourgeois democrat. Che was known to be a Communist—he was often referred to as ‘the Red flea in Fidel’s ear’—but his contempt for the Cuban Communist Party was considered troublesome. Finally, Mr. Anderson relates, the Kremlin sent a top official, Nikolai Metutsov—a jowly, large-eared, beetle-browed man—to Cuba to get a fix on Che. The results were comic. Mr. Metutsov wound up talking all night with Che and being seduced not just by his revolutionary zeal (which reminded Mr. Metutsov of the early Bolsheviks) but also by his romantic pallor, his poet’s eyes and his flowing chestnut hair. By morning, Mr. Metutsov told Mr. Anderson, ‘I confessed my love for him because he was a very attractive young man. . . . I felt attracted to him, do you understand? . . . He had very beautiful eyes. Magnificent eyes, so deep, so generous, so honest.’

For all Mr. Anderson’s Soviet-bloc access, his portrait of Che is refreshingly nonpartisan. Ernesto Guevara grew up in a family of eccentric and impecunious Argentine aristocrats (an uncle was Ambassador to Cuba while Che was in the mountains), and Mr. Anderson describes him as possessing an ‘unusual combination of romantic passion and coldly analytical thought.’ He reports that Che was tone-deaf, didn’t dance and loved nothing more than mathematical puzzles. From childhood he was crippled by asthma, and his mother once explained to the journalist Eduardo Galeano that Che ‘had always lived trying to prove to himself that he could do everything he couldn’t do.’ Mr. Galeano wound up labeling Che the Jacobin of the Cuban revolution, and Che did, in fact, have a frightening cruel streak. Not long after he and Castro established themselves in the Sierra Maestra, for example, they unmasked a traitor. The man’s fate was obvious, but no one wanted to be the executioner until Che pulled out his pistol and shot him through the head. Che was a doctor and, in his diary, he noted in clinical detail the bullet’s points of entry and exit. Later, after Batista was vanquished, Che was put in charge of the revolutionary firing squads. Asked by a friend how he could live with this role, he responded, ‘Look, in this thing you have to kill before they kill you.’

“From adolescence Che displayed a strong wanderlust, and Mr. Anderson’s narrative traces his youthful travels around South America to Guatemala, in 1954, where he lived through the American-directed coup against the elected Government of Jacobo Arbenz Guzman. Until he reached Guatemala, Che had been anti-American but also anti-Communist. Guatemala made him a Communist, and Mr. Anderson argues that after the Cuban revolution he became the principal architect of both Cuba’s turn away from the United States and its military and economic realignment with the Soviet Union. It was the start, to put it mildly, of a vexed relationship. Che quickly became disillusioned with shoddy Soviet goods and the lumpish corruptions of Soviet advisers. More and more he turned his attention to the Liberation Department, a supersecret agency hidden within Cuba’s security apparatus that was designed to foment world revolution.

In the aftermath of the near disaster of the missile crisis, the Soviets made it clear that they had limited interest in Che’s adventurism. Eventually, at a 1965 conference of African and Asian revolutionaries in Algiers, he exploded, publicly lambasting the Russian leaders as ‘accomplices to imperialist exploitation.’ When he returned to Cuba, he resigned from all his posts and dropped out of sight. Traditionally, historians have contended that this reflected a break with Castro, who had been forced into an increasingly tight Soviet embrace. But Mr. Anderson argues convincingly that Castro was operating on multiple tracks: while publicly toeing the Soviet line, he was privately entertaining Che’s argument that the only way to break Cuba’s isolation was to create revolutions throughout Latin America.

As the Liberation Department stepped up its involvement with Latin America, Che, the internationalist, left for Congo, where he and several hundred black Cuban volunteers joined forces with Laurent Kabila (who is once again making news in Zaire) in a fight against Joseph Mobutu and a group of mercenaries led by the white South African Mike Hoare. It was a fiasco. While Mr. Kabila sped around the Tanzanian capital of Dar es Salaam in a green Mercedes, his troops, along with the Cubans, festered at the front and were eventually routed.

“Undeterred, Che returned to Cuba to prepare for his departure for Bolivia, which Havana had designated as host country for the impending subversion of Latin America. By this time, however, Che had become so widely hunted by the C.I.A. that his overseas travel had to be conducted in deep disguise. To prepare him for his trip to Bolivia, the Cuban secret service plucked all the hair off the top of his head; when he went to say his final farewell to his family, his own children didn’t recognize him.

At the end of the Congo debacle, Che had been confronted by a loyal follower from the days in the Sierra Maestra, who reproached him for possessing an inflexible worldview, for refusing to adapt to changing realities. This certainly seems to have been the case in 1967 in Bolivia, where Che and most of his followers were quickly hunted down and killed. Local Bolivians thought that in death Che looked like Jesus, and they snipped locks of his hair. In Cuba, a million people turned out for his wake.

Mr. Anderson does a masterly job in evoking Che’s complex character, in separating the man from the myth and in describing the critical role Che played in one of the darkest periods of the cold war. Ultimately, however, the strength of his book is in its wealth of detail. Not the least of the remarkable stories Mr. Anderson tells is of going to Miami to look up Felix Rodriguez, the leader of the C.I.A. team that helped chase Che down (he later worked with Oliver North in the Iran-contra affair). Mr. Rodriguez showed him his most prized possession—Che’s last, half-smoked wad of pipe tobacco, frozen inside a glass bubble in the handle of Mr. Rodriguez’s favorite revolver.”

–Peter Canby, The New York Times, May 18, 1997

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.