Carolyn Burke’s Foursome is published today. She shares five books that inspired, spurred, or otherwise helped her to think of writing group biography.

Charmed Circle: Gertrude Stein & Company by James Mellow

Years before it occurred to me to try my hand at biography, reading James Mellow’s Charmed Circle: Gertrude Stein & Company felt like taking a voyage into another time, when the Steins presided over the unconventional cast of characters who came to their Paris salon. This book showed me that one might paint a large-scale portrait of a creative coterie while looking carefully at their work to illuminate the cultural currents of the day. I was also impressed by Mellow’s integrity in his account of the couple formed by Stein and Alice B. Toklas, the one who (as Stein wrote) first said ‘yes’ to her writing.

Jane Ciabattari: Stein’s circle was indeed inspiring for generations to come. Mellow is even-handed in his approach, skipping the gossipy angle when it comes to explaining how things went wrong with Hemingway, for instance. Is his integrity a matter of content? Tone? Voice?

Carolyn Burke: All three. Upon reflection, I think Mellow’s integrity derives from his rare blend of affection for his subjects, judicious use of detail (down to the cakes served at the Stein salon), and persuasive readings of literary texts interspersed throughout the narrative. The reader always feels that she is in good hands.

Positively 4th Street by David Hajdu

For a life of Lee Miller, I was pondering how to portray Miller’s rapport with Man Ray in a new light when I came across Hajdu’s Positively 4th Street—a group biography that interweaves “the lives and times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Fariña, and Richard Fariña” (the book’s subtitle). Hajdu showed me that one could write about a similar time (the 1960s) and a milieu (modern day Greenwich Village). (I had hung out at the some of same coffeehouses where this quartet courted each other and wrote their songs). Reading Hajdu’s book at that time encouraged me to paint my portrait of French Surrealism in the 1930s.

JC: Hajdu’s book captures the foursome before their lives and truths were touched by fame. (He did extensive interviews.) When writing about such widely known characters, how does the biographer sift through to the gold?

CB: I asked myself this question at the start of my next book, a life of Edith Piaf. After reading everything published about a famous person, you come to a sense of which sources are reliable, and which anecdotes or judgements have simply been repeated from one book to another. The gold may reveal itself in interviews with the subject’s contemporaries, or in re-readings of her own work (Piaf’s more than 100 songs helped me to grasp her engagement in the creation of her legend). Sometimes it’s a matter of timing, or serendipity, as when the writer gains access to new material (the recent release of Piaf’s correspondence with her mentor revealed little-known aspects of her character, including her love of poetry and her spiritual bent). The gold, I think, shines through familiar tales about well-known subjects with a gleam all its own.

Portrait of a Marriage by Nigel Nicolson

After reading several lives of Bloomsbury artists and writers, I came to value Nicolson’s Portrait of a Marriage, about the unusual partnership of his parents, Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson. I was impressed by Nicolson’s version of their rapport, which afforded them great personal and creative freedom, and his decision to tell their story by including poems, letters, autobiographical texts, and several narratives of his own. This way of writing biography, with Virginia Woolf and others in the background, brought me into their lives with greater immediacy than other books about their circle, which often seemed too self-contained to be inviting to the reader.

JC: Indeed, Nicolson offers a fresh approach, including those journals. He begins with V. Sackville-West, July 23, 1920, writing, “Of course I have no right whatsoever to write down the truth about my life, involving as it naturally does the lives of so many other people, but I do so urged by the necessity of truth-telling, because there is no living soul who knows the complete truth; here, may be one who knows a section; and there, one who knows another section: but to the whole picture not one is initiated.” Does that not describe the biographer’s challenge?

CB: Most biographers, I imagine, are simultaneously aware of the limits of their knowledge and the need to shape a narrative nevertheless. At the same time, especially when narrating the lives of couples, groups, or both at once, one works with the understanding that (as Henry James wrote) “relations stop nowhere, and the exquisite problem of the artist is eternally but to draw, by a geometry of his own, the circle within which they shall happily appear to do so.” While writing Foursome, I became conscious of the need to square the circle by emphasizing the role of Rebecca Salsbury, the thread that wove together the two couples’ lives.

Just Kids by Patti Smith

Just Kids came out when I was finishing No Regrets, my biography of Piaf, which takes the well-known story of her many amours and sees them as occasions for shared creative inspiration. Smith’s tale of the couple she formed with Robert Mapplethorpe when they were innocents abroad in New York bohemian circles of the 60s and 70s offered still another way of telling a love story—one energized by the partners’ mutual desire to make their mark aesthetically, Smith with her unique blend of poetry and rock music, Mapplethorpe with his provocative photographs. The narrative, spanning two decades, begins and ends with Mapplethorpe’s death, and Smith’s promise to him “to write our story.”

JC: Smith’s structure is so elegant—circular, as you point out, with eddies of memory flowing in some organic way. Within pages, she describes her own poetry readings, the first time she went into CBGB’s, her first recording at Electric Lady, then jumps to Mapplethorpe’s artistic explorations, his relationship with Sam Wagstaff, and then back to their own relationship: “At its best, our friendship was a refuge from everything, where he could hide or coil like an exhausted baby snake,” she writes. Did Just Kids influence your work in structuring Foursome?

CB: The idea of close relationships as a form of refuge found its echo in Foursome, but otherwise not so much. Although Smith’s voice kept me company while I wrote, my project was different from hers. I had to find or invent ways to weave the threads of my narrative while constructing a forward-moving chronology rather than a retrospective account, one that allowed my characters’ lives to unfold in all their uncertainties about the future. Also, the story I was telling needed to look at the effects on them of two world wars, the Depression, and major societal shifts. I enjoyed the work of plotting the turns and returns of their relationships across the grid of temporality as well as writing my farewell to them, a final chapter called “Envoi.”

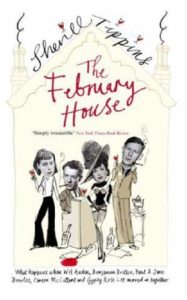

February House by Sherill Tippins

Sherill Tippins’ February House is a group portrait with a large and unlikely cast of characters—W.H. Auden, Carson McCullers, Jane and Paul Bowles, Benjamin Britten and Gypsy Rose Lee—all of whom shared a house in Brooklyn during the 1940s. The book’s tight focus recreates what was a sort of on-going salon, both like and unlike that of the Steins decades earlier, and makes lively use of all that these improbable housemates wrote and discussed during the year that they lived together.

JC: Tippins calls February House in Brooklyn Heights “romantic, bohemian chaos.” Imagine the dinner table talk, the parties with all these young artists. Carson McCullers working on Member of the Wedding and The Ballad of the Sad Café, Britten working on Peter Grimes, and Stripper Gypsy Rose Lee, working on The G-String Murder, and the rest. Tippins focuses more on their social interaction than the work. How do you strike the balance between relationships among your subjects and expositions of their work?

CB: A crucial issue in writing the lives of artists! With Charmed Circle in mind, I tried to strike a balance between the shifts in relationships among the four and related developments in their work. This balancing act varies from chapter to chapter as they inspire, influence, and sometimes irritate each other. When describing the rivalry that arose between Stieglitz and Strand, I focus on the two men’s nude studies of their muses—Stieglitz’s of both O’Keeffe and Salsbury, by then married to Strand, and Strand’s nudes of his wife. In a different way, Rebecca’s discovery of the artificial white roses that she painted in Taos and showed to Georgia, who adopted them as her subject, helped Rebecca see herself as the other woman’s peer while also setting up the sense of competition that colored their friendship. As I neared completion of the book, it was rewarding to demonstrate affinities in the foursome’s artistic practice through the choice of illustrations, which serve as mini art galleries within the larger context of the story. We learn, by this and other means, about the impact of aesthetic choices on an artist’s personal life. Or as O’Keeffe’s teacher Arthur Dow wrote, “In the relations of lines to each other [one] may learn the relation of lives to each other.”

*

· Previous entries in this series ·