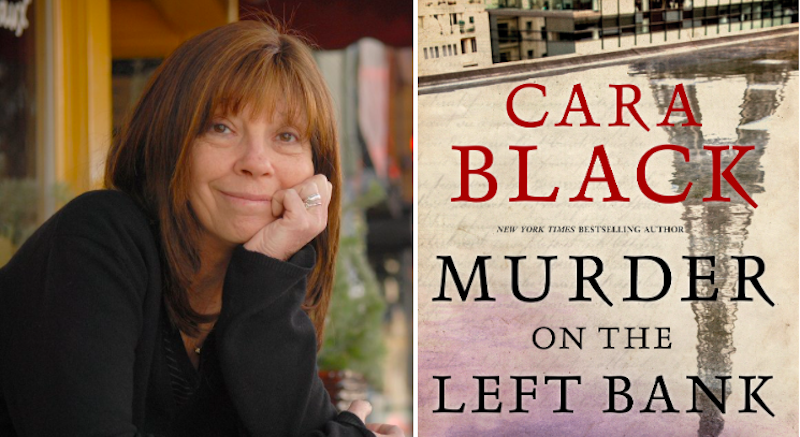

Cara Black’s new novel, Murder on the Left Bank, the eighteenth in her Aimée Leduc series, has just been published by Soho Press. We asked her about five books that reveal aspects of Paris.

Maigret Loses His Temper, Georges Simenon

When a body is discovered by the infamous Pére Lachaise cemetery Inspector Maigret investigates. Not only did the story grab me but illustrated how each quarter of Paris, each social class, had, you could say, its own way of murder.

Jane Ciabattari: Was Simenon’s Maigret an inspiration for your Aimée Leduc series?

Cara Black: Absolutely. Years ago, I found this book by Simenon on my father’s book shelf. The story and characters opened a window onto a Paris that I never suspected or knew existed. Inspector Maigret investigated crime among the upper class and the underbelly of Paris, from the dark alleys to chandelier-lit salons. His stories were set in the past but I wanted to frame this in the Paris of “today” (the nineties) with a modern young Parisiene, Aimée Leduc. She’s a PI, half-American and half-French, whose cases take her to the darker side of the City of Light.

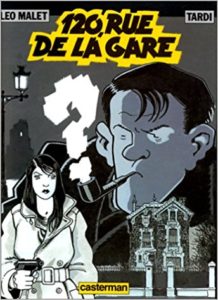

120 rue de la Gare, Léo Malet

Malet is considered the father of French Noir. Here, in the first of Malet’s series, we’re introduced to the wisecracking PI Nestor Burma, a returnee from a German POW camp, who solves crimes with panache.

JC: Do you think of your series as French Noir? How did reading about PI Nestor Burma influence Murder on the Left Bank, which opens with Leo Solomon, now in his eighties, who had been a POW in a German stalag, calling upon a young attorney to hand over proof of police corruption by an organization known as The Hand, which had killed Aimée Leduc’s father.

CB: My series evokes French Noir. While Noir writers influenced me, my stories differ. In Noir, the character hits disaster on the first page and it’s downhill from there—a spiral into ruin. In Murder on the Left Bank, while Aimée Leduc struggles and hits the wall, she fights and gets resolution—unlike Noir. Not all the ends are tied up in Aimée’s investigation, but justice, in some form, is served. Malet, like Burma, was a former POW returned from a German Stalag, and I guess, I wrote this as an homage to Malet, a huge influence on me. Léo Solomon is a character who, in my eyes, could have been a POW in Malet’s/Burma’s Stalag during the war. I wanted to explore how choices made in the past reverberate in present day. How survival can cost. And to explore the 13th arrondissement, so different now from Malet’s time, which intrigued me.

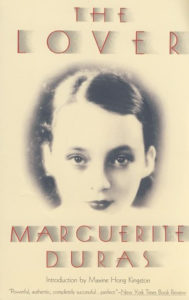

The Lover, Marguerite Duras

This novel won the Prix Goncourt in 1984 and helped my understanding of France and its colonial past. Duras’ writing is sensuous, tinged by melancholy, evocative and swept me to another time and place.

JC: How did you research Duras’ time and French Indochina as you were working on Murder on the Left Bank, which has key characters with Cambodian heritage?

CB: I visited Cambodia and found a country of young people who spoke English yet had grandparents who spoke French and there were baguettes in the market. The vestiges of some French architecture remains and evokes the past Duras wrote about. Yet in Paris, where the largest group of Cambodians live, the quartier is called ‘le petit Asie’ (with Vietnamese, Laotians, Chinese). Here I searched for the generation who grew up in the colonial times, Indochine and the echoes of Duras. While I was motivated by Duras, what I found were the younger generation whose parents had fled Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge who followed the French. Since my setting and place is organic, a character in the story, it needs to reflect the quartier and its unique ambiance. So to bring the flavor of this slice of Paris it was important to be reflective of contemporary times.

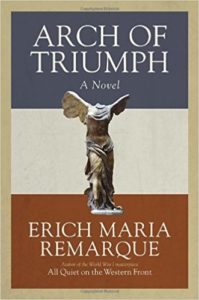

Arch of Triumph, Erich Maria Remarque

I read this classic years ago and go back to it for the atmosphere of pre-War Paris, to walk those rainswept streets by the monument, pass the one star hotels home to refugees. A muted, evocative novel about a man without a country in a doomed love affair.

JC: Was this atmosphere an inspiration for scenes you set in a two-star hotel owned by an Arab family who hid a Jewish family during the war, and whose rooms are now inhabited by economic refugees, pensioners laid off after factories were demolished in the 1970s.

CB: Definitely. Every generation, sadly, seems to contend with a diaspora—a generation of people who have lost their home, livelihood and country. Yet the highlight for me were stories rarely heard of how people, living on the edge came together in need and helped each other. This happened, as told to me, in this quartier which in the 19th century was a village on the Paris outskirts, then swallowed by the city and site of French factories, now gone, a newer group of Asian immigrants—an emblem of the changing Paris yet holding deep traces of it’s storied past.

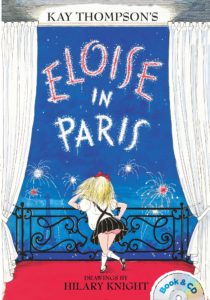

Eloise in Paris, Kay Thompson

Eloise, the six-year-old Plaza hotel resident, goes with Nanny to Paris; what’s not to love? And the illustrations of Eloise’s friends by Hilary Knight are the coup de grâce: Richard Avedon takes Eloise’s passport photograph; Christian Dior prods her tummy, while his young assistant, Yves Saint Laurent, looks on; and Lena Horne sits at an outdoor cafe.

JC: Aimée Leduc’s baby daughter and her nanny play a big part in your recent novels, but Chloe isn’t even a year old. Any Eloise moments coming up?

CB: Chloé is approaching toddlerhood and will be taking her first steps in the next book. She’s a little Parisienne to the core and her mother’s daughter. Chloé definitely has an eye on her mother’s scarves as we’ll see and goes to “work” with mama at Leduc Detective when her nanny has the day off. René, Aimée’s partner and Chloé’s godfather, longs for the day he can start teaching her to code and feels she’s an instinctive math genius.