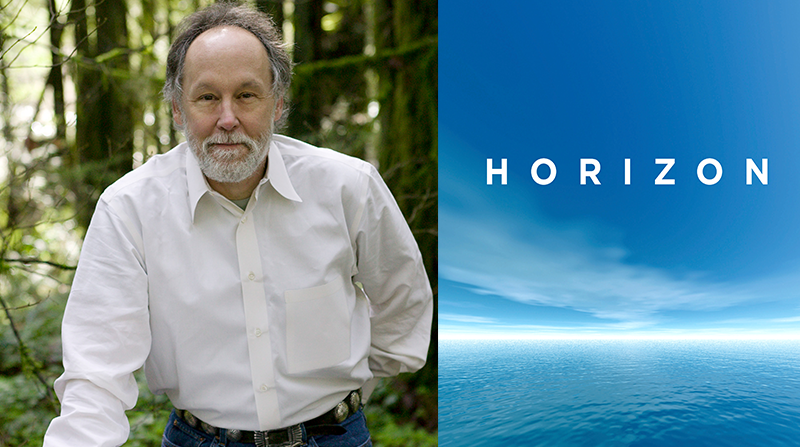

Barry Lopez’s Horizon is published this month. He shares five books about traveling the world.

Libyan Sands: Travel in a Dead World by Ralph A. Bagnold

Libyan Sands is a record of Bagnold’s experience exploring the Libyan desert while he was serving in the British army. He became a scientist specializing in the movement of wind-blown sand, and his work is a charming exploration of, if you will, the biological life of a geological entity.

Jane Ciabattari: This one goes back to 1935, and influenced Michael Ondaatje’s novel The English Patient. Imagine a small group of British officers stationed on the outskirts of Cairo, in the mid-1920s, traveling by Ford Model T into the desert. “We merely felt, consciously and unashamedly, the exciting mental kick of an apparent breakdown in the flow of Time, whereby one sees and touches the buildings and belonging, perfect as of today but oddly different, of a people inconceivably old,” Bagnold writes. Have you had similar experiences? In the desert?

BL: I have had experiences like those that Bagnold describes but most of them have been in the polar regions, not in deserts. In the polar regions, I’ve had experiences with time that were profoundly disorienting. This is partly because in high summer—or deep winter, for that matter—your daily experience is 24 hours of sunlight or 24 hours of darkness. The “day” is 365 days long, so that is the setup. The absence of noise contributes to a sense of timelessness and, as is the case in both polar regions, the only paths you see in the land, for the most part, are made by animals. The northern polar regions are very lightly populated. No matter where you are, you can go for weeks on end and see no one. In Antarctica the only inland animals you see are birds, who are just passing through in the coastal regions. For me, the effect of all of this is to feel one is standing on a tabula rasa. The land is all new, fresh, numinous. Anything might happen.

Dersu Uzala by Vladimir Arsenyev

Arsenyev’s Dersu Uzala was made into a movie called Dersu, the Trapper by Akira Kurasawa. It recounts Arsenyev’s friendship with an indigenous Nanai man in far eastern Russia and includes many of Uzala’s insights into that landscape.

JC: “I finally realized that Dersu was not a simple man,” Arsenyev writes. “This was a tracker before me, and I couldn’t help but think of the heroes of James Fenimore Cooper and Thomas Mayne Reid.” He’s probably best known through the film, which won an Academy Award, but Dersu Uzala was one of the last remaining members of the Upper Ussuri branch of the Gold tribe, Aresenyev writes. “There were only three of them left in 1901 — these were Kapka Belday, Oko Belday, and Dersu Uzala. The former two were killed in spring of that year by the Khunkhuz on the Noto River, and Dersu died in 1908, in the Khekhtsira Mountains, some 36 kilometers from Khabarovsk.” Are there passages you can point to that show us his understanding of the taiga?

BL: Whatever passage I might point out would trigger a sense of wonder, but to understand a vision of the land distinct from the one you as a reader might be familiar with, you have to move on from these singular, eyebrow-raising moments to a sense of a world where everything is put together differently. The idea behind my recommending Dersu Uzala would be for a reader to follow up with other books like, say, Make Prayers to the Raven, in order to develop a deeper sense of how complex the world outside the self is, to appreciate the depth and extent of the wonder, the miracle.

Make Prayers to the Raven: A Koyukon View of the Northern Forest by Richard K. Nelson

Richard Nelson’s Make Prayers to the Raven became a kind of bible for me years ago. Nelson is a highly skilled anthropologist and field biologist who apprenticed himself to Koyukon people in Central Alaska and then wrote a book, which might have been called a “A Field Guide to the Animals of the Alaskan Interior,” written from the point of view of a Koyukon person. It’s immensely illuminating about the relationships between humans and animals.

JC: Nelson’s is an ethnographic study, and a natural history. I’m struck by Nelson’s recognition of Steven and Catherine Attla, the couple about fifty years old who were his principal instructors in the Koyukon—both of whom had an incredible mastery of both cultures. How have your own “instructors” in cultures outside your own influenced your work?

BL: Catherine Attla, whom Richard Nelson introduced me to, was actually one of my instructors when I was trying to develop a “native eye” in the Arctic. What I and other non natives are trying to understand is how to develop a conversation with the landscape in question. To do that, one needs to be tutored. It makes sense, then, to work with the people who have been in conversation with that landscape for the longest time. If you go out there with a set of bird guides, a handbook on the local mammals, and a stack of topographic maps—which is always a good idea in any situation where you’re starting from scratch—you remain linked with a way of knowing that has been prepared by a non-indigenous culture. The thing you want to do is to learn the birds, the animals, the topography, and so on from another perspective. This allows you to gain a binocular view of the landscape instead of the monocular view you arrive with in this new landscape. To answer your question more directly, I would say it’s imperative to give yourself over to indigenous people when you’re traveling in their regions. If you’ve done your homework, you’re arriving with a reasonably good sketch of the area. You want to improve on that for the sake of the reader. You want to see deeper so the reader can.

The Ice: A Journey to Antarctica by Stephen J. Pyne

Steve Pyne’s The Ice is one of the best books anyone has ever written about Antarctica.

JC: What makes it so special?

BL: What makes Steve Pyne’s The Ice so extraordinary is Steve Pyne. He brings a perspective that, to my mind, is more encompassing, more subtle, more exciting, than the engaging but sometimes cursory or ordinary observations you find in other travel books.

The Road to Botany Bay: An Exploration of Landscape and History by Paul Carter

Paul Carter’s The Road to Botany Bay is a brilliant commentary on the conceptual organization of Australian space by imperial British colonizers. It’s one of the best books I’ve ever read about landscape and undefined space.

JC: Carter asks, “What was the place like before it was named?” And he strips back the landscape to its essence. How would you define the influence of Carter’s book, first published in 1987, in traversing new historical ground, as he puts it?

BL: Paul’s book had a terrific impact on me. I love to read a mind that is insightful, alert, hungry, and free of sectarian views—like Steve Pyne’s. Paul also brings to the page a great deal of formal education in philosophy, anthropology and geography. He’s exciting to read. He propels you farther into the country of your own perceptions.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·