To die, it’s easy. But you have to struggle for life

*

“Maus: A Survivor’s Tale is a Holocaust memoir with a remarkable difference. True, one thread of it recapitulates the all-too-familiar story of the Spiegelman family in Poland from 1935 to 1944 struggling to avoid the inevitable fate of Auschwitz. There are the loss of property, the dawning sense of peril, the black markets, the ‘selections,’ the cellar hiding places, the briberies, the betrayals and finally the truck to the gate with the sign over it reading, ‘Arbeit macht frei.’

But there are four unusual innovations to the way Mr. Spiegelman has told his story. In ascending order of surprise, these are as follows: First, he explores the relations of the surviving generation and its children, especially the guilt visited by the former upon the latter. The adventures of the Spiegelmans in Poland are told by Vladek, the surviving family member, to his grown-up son, Artie, who begins his narrative: ‘I went out to see my Father in Rego Park. I hadn’t seen him in a long time—we weren’t that close. He had aged a lot since I saw him last. My Mother’s suicide and his two heart attacks had taken their toll.’

Second, Mr. Spiegelman brings considerable humor to the telling of his story. Scarcely has Artie removed his coat and handed it to Mala, his father’s present wife, when Vladek begins to berate her: ‘Acch, Mala! A wire hanger you give him! I haven’t seen Artie in almost two years. We have plenty wooden hangers.’ Vladek recounts much of his Holocaust memories while working out on an exercise bike or counting out his daily ration of pills. So crotchety and irrational is Vladek’s behavior that when Artie wonders if ‘the war made him that way,’ Mala responds: ‘FAH! I went through the camps . . . All our friends went through the camps. Nobody is like him!’

“Third, Maus is a comic book! Yes, a comic book complete with word balloons, speed lines, exclamations such as ‘sob,’ ‘wah,’ ‘whew’ and ‘?!,’ and dozens of techniques for which I simply lack the terminology. The average frame is two to three inches square and crowded, even shaggily drawn (except for one starker section, called ‘Prisoner on the Hell Planet: A Case History,’ involving the author’s mother’s suicide) though subtly elegant and expressive if one pays attention to details. The style is eclectic, echoing everything from Krazy Kat to Gasoline Alley. Naturally, the effect of treating such a subject this way is shocking at first. But with a speed that is almost embarrassing to confess, this reader was transported back to the experience of reading World War II comics such as Blackhawk or Captain Marvel.

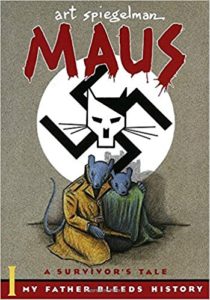

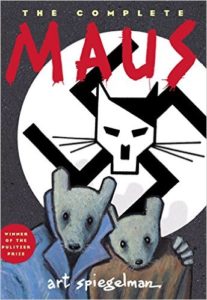

Finally, and perhaps most surprisingly of all, the Jewish characters in the book are all portrayed as mice, while the Nazis are cats, the Poles are pigs and the few non-Jewish Americans that appear are dogs. To portray a game of cat and mouse is one obvious purpose of Mr. Spiegelman’s provocative gambit, as well as ironically to echo the book’s epigraph, which is Adolf Hitler’s remark, ‘The Jews are undoubtedly a race, but they are not human.’

But the impact of what Mr. Spiegelman has done here is so complex and self-contradictory that it nearly defies analysis. One obvious point would seem to be that by scaling down the Holocaust to the dimensions of an animal fable—or approaching ‘the unspeakable through the diminutive,’ as the jacket copy so felicitously puts it—the experience of European Jewry becomes something to be contemplated in less than apocalyptic terms. But leaving aside whether such an effect is desirable, I don’t think that it is the main purpose of Maus, and even if it is, then it remains somewhat beside the point.

“Instead, the medium is the message. By claiming the Holocaust as a subject fit for comic-book art, Mr. Spiegelman is saying that the children of the survivors have a right to the subject too and have their own unique problems, which are comic as well as tragic. Even the narrative content reflects that point. By having Vladek recount the farcical elements of his prewar courtship of the author’s mother, Mr. Spiegelman is saying that life went on before catastrophe struck. By making bittersweet comedy of life in Rego Park with Vladek, he is saying that life continues to go on.

The ultimate irony lies in the closing anecdote of Maus. Artie presses his father to produce his mother’s diary, so he can trace her experiences after his parents were separated upon their arrival at Auschwitz. Vladek finally admits: ‘After Anja died I had to make an order with everything . . . these papers had too many memories. So I burned them.’ Artie is enraged. After promising his father that he’ll visit more often, he heads for home, muttering to himself, ‘Murderer.’

The irony of this utterance—in the light of the six million—does not diminish the enormity of the Holocaust. Yet given Mr. Spiegelman’s art, it asserts the right of succeeding generations to treat their ancestors’ experience with less than awe-filled reverence. For those who survived, life goes on. And for their children, life, for all its unusual complications, can have its moments of humor”

–Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, The New York Times, November 10, 1986