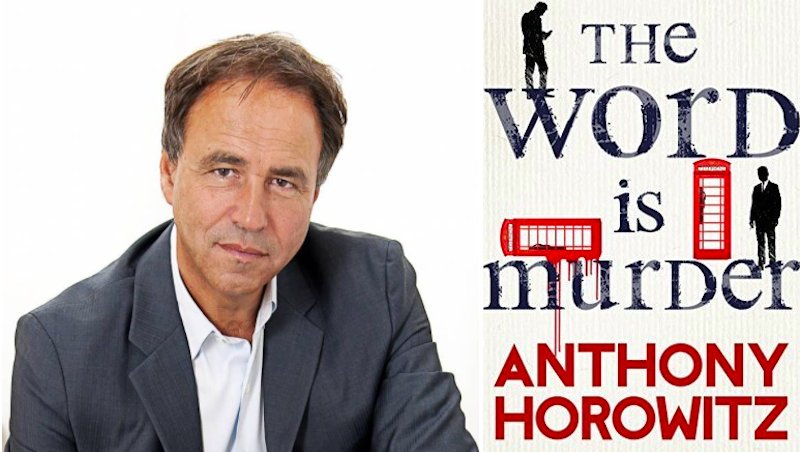

Anthony Horowitz’s new book, The Word Is Murder, has just been published by Harper. We asked the novelist to talk about five books in his life and he chose the following murder mysteries.

*

William Goldman, Adventures in the Screen Trade

A great book about writing…and the reason why I wrote The Word Is Murder.

Jane Ciabattari: When did you read Adventures in the Screen Trade?

Anthony Horowitz: I read it at the very start of my television and film-writing career when I was in my twenties and still think it’s one of the most entertaining and insightful books ever written about Hollywood. Having worked across so many media in my own career, I briefly considered writing something similar myself. I even had a title—Ten Million Words—which is approximately the number of words I myself have produced. But it didn’t work. My own version was too insular and frankly rather dull.

But the thought wouldn’t go away and, years later, I had the idea of folding my own experience as a writer into a murder mystery, actually putting myself as a character into my own book so that I could discuss the techniques of writing even as I was using them. And that was how The Word is Murder began.

Agatha Christie, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd

For its brilliant construction and extraordinary surprise ending.

JC: This third novel in her Hercule Poirot series, published in 1926, was voted the best crime novel ever by the British Crime Writers’ Association in 2013. Its surprise ending changed the genre, right? What makes Agatha Christie so great?

AH: I have always loved Agatha Christie. I read pretty much the entire collection in my “gap year,” travelling overland from Australia to London when I was 18. What I most admired about her was her structure and technique. The core of a murder mystery is actually very simple. A+B=C. One person (A) kills another person (B) for a reason (C). But Christie found an incredible number of permutations for this formula—and Roger Ackroyd is one of her most ingenious. Agatha Christie always plays fair with the reader. All the clues are there. The solution is always hiding in plain sight and you kick yourself when you don’t get it.

Conan Doyle, The Hound of the Baskervilles

Watson is particularly active in this story.

JC: You’ve written Sherlock Holmes books, and James Bond books, the Alex Rider series, a TV mystery series, Foyle’s War. In Magpie Murders your narrator is the editor of a mystery writer; in your new book your narrator is the writer himself. And you show us how your author comes up with ideas, and how he shapes the book. What made you decide to add yourself as a character?

AH: When I decided to write a lengthy series of murder mysteries—and I’m planning nine or ten books about Daniel Hawthorne—the first question I asked myself was: how can I do something completely different, something that has never been done before? My detective could be old, young, male, female, French, German etc…but all these were just variations on a well-worn theme. But then I began to consider the relationship between the author, the detective and the sidekick and saw that, by making myself Watson to Hawthorne’s Holmes, I would change everything at a stroke. Instead of becoming all-knowing, I would be the most ignorant person in the book.

That said, I’ve been very careful not to put too much of myself into the book. At the end of the day, I’m only the narrator. How much of what I write is true? I’m told that many readers have gone to Google to try to find the answer to that but I’m afraid my lips are sealed.

Christopher Isherwood, Mr. Norris Changes Trains

The story of an unlikely friendship.

JC: Is Isherwood’s book an influence on your author/narrator, who comes to witness Hawthorne in action and also discover his secrets?

AH: I always knew that I would have an antihero as my detective although I was aware it might be a gamble. If readers don’t find anything in Hawthorne to like or admire, then they won’t enjoy the read. Hawthorne is difficult, acerbic…and some of his opinions are quite objectionable. I hate the way he calls me Tony! But he’s also brilliant and generally means well.

Somewhere in the back of my mind was another book I read when I was young. It’s set in Berlin in the early 1930’s. Arthur Norris is shabby, narcissistic, mysterious, and perennially broke—but Isherwood still succeeds in making him attractive. One of the things I enjoyed about The Word is Murder is the way that the narrator begins to investigate the detective. What has happened to him to turn him into the man that he is? I have a vague idea of the answer bit will take me nine or ten books to pin it down.

George Orwell, Keep the Aspidistra Flying

Another book with a writer as the central character and an influencer throughout my life.

JC: When did you first read Keep the Aspidistra Flying? And how has it influenced your choices?

AH: I’ve always been fascinated by the business of writing. Where do ideas come from? How do you structure a novel? Why, even, do we read? George Orwell’s 1936 novel is a brilliant exploration of a not very successful writer, Gordon Comstock, and his relationship with what he calls “the money god.” Should he risk becoming a high-minded, literary poet? Or should he continue as a well-paid copywriter at Albion Advertising? I actually began as a copywriter so this has a particular resonance for me. A recent report has suggested that crime novels are now the most popular type of fiction in the UK. I wonder if it is possible to be popular, to write novels that are essentially entertainments and yet at the same time to bring something more to the table. That’s what I’m trying to do with The Word is Murder (and Another Word for Murder, which I’m writing at the moment). Gordon Comstock is a warning of what happens when it all goes wrong.

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.