He liked the grand size of things in the woods, the feeling of being lost and far away, and the sense he had that with so many trees as wardens, no danger could find him.

*

“Sometimes, if you wander long enough out-of-doors, you look up and find yourself in a suddenly devastating place: on a glittering slab of granite, say, hanging a thousand feet above a mountain lake. Your blood quickens, the clouds stretch, the light turns everything to gold and something enters you, shakes you, seizes some root of your soul and pulps it. Maybe you make your way down to the lake for a swim, or just sit beneath the sky for an hour, dazzled, but what lasts is the feeling that you have found something important, something precious, something that would be world-renowned if only it weren’t so hard to find.

It’s a proprietary feeling, too, when you find a place — or a song, or a painting, or a sandwich — that you love, that moves you. You want to share it with only a few other souls, believers, maniacs, folks who won’t trample on it. Because who wants to see her sacred meadow flattened by the sandals of tourists?

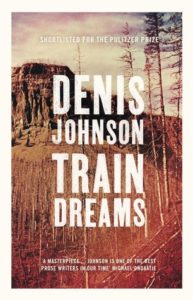

“I first read Denis Johnson’s novella Train Dreams in a bright orange 2002 issue of The Paris Review and felt that old thrill of discovery. The story concerns the life of Robert Grainier, a fictional orphan shipped by train in 1893 into the woods of the Idaho panhandle. He grows up, works on logging gangs, falls in love, and loses his wife and baby daughter to a particularly pernicious wildfire. What Johnson builds from the ashes of Grainier’s life is a tender, lonesome and riveting story, an American epic writ small, in which Grainier drives a horse cart, flies in a biplane, takes part in occasionally hilarious exchanges and goes maybe 42 percent crazy.

It’s a love story, a hermit’s story and a refashioning of age-old wolf-based folklore like ‘Little Red Cap.’ It’s also a small masterpiece. You look up from the thing dazed, slightly changed.

Every once in a while, over the ensuing nine years, I’d page through that Paris Review and try to understand how Johnson had made such a quietly compelling thing. Part of it, of course, is atmosphere. Johnson’s evocation of Prohibition Idaho is totally persuasive … The novella also accumulates power because Johnson is as skilled as ever at balancing menace against ecstasy, civilization against wilderness. His prose tiptoes a tightrope between peace and calamity, and beneath all of the novella’s best moments, Johnson runs twin strains of tenderness and the threat of violence.

“In all the paragraphs of Train Dreams, one feels vaguely unsettled; one feels the seams of history might unravel at any moment and the legends of the woods come slipping through. The novella has flaws, of course: tufts of seemingly irrelevant material stick out here and there, miscellaneous fevers, peripheral anecdotes, a Chinese deportation, a big kid with a weak heart. But its imperfections somehow make the experience better, more real, more absorbing, and it might be the most powerful thing Johnson has ever written.

But I’ve decided now, after thinking it over for almost a decade, that what ultimately gives Train Dreams its power is simpler. It is the story’s brevity.

The novella runs 116 pages, and you can turn all of those pages in 90 minutes. In that hour and a half the whole crimped, swirling, haunted life of Robert Grainier rattles through the forests of your mind like the whistle of the Spokane International he hears so often in his dreams.”

–Anthony Doerr, The New York Times, September 16, 2011

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.