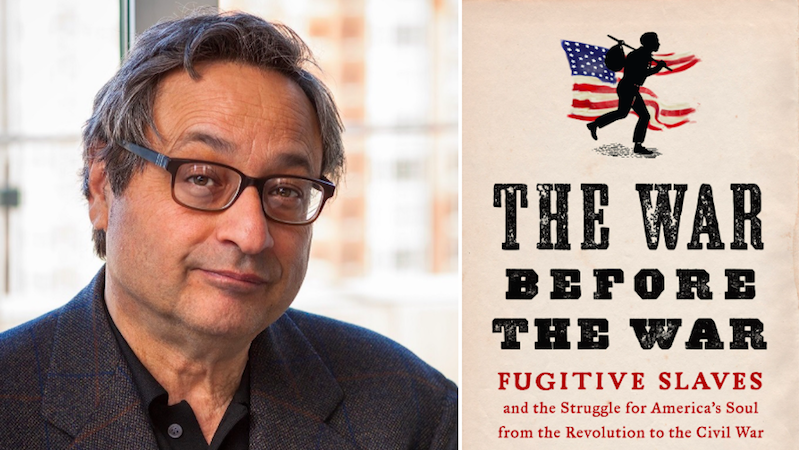

Andrew Delbanco’s The War Before the War is published this month. He shares five classic American novels he enjoys teaching, noting, “I’ve been teaching classic American literature to college students for almost 40 years, and while some books have been banished from the category of ‘classic’ and others have been invited in, certain works continue year after year to disturb, confuse, delight, or devastate my students—or, more likely, all of the above.”

The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter is the story of a love affair in early New England between a charismatic young preacher and a beautiful young woman, Hester Prynne, whose older desiccated husband leaves her to struggle on her own between her principled virtue and her latent passion. Passion wins out, and the result is an illegitimate child whose very existence scandalizes the Puritan community. I find that students—at an age when they are working out their own feelings about sexuality and responsibility—are drawn into Hester’s inner conflict as she revels in the joy of freedom but fears for her daughter in a world where any woman unconfined by chastity or monogamy is shunned and stigmatized. As no one needs to be reminded in the “Me Too” era, the rules governing sexual relations are always changing—but the perennial question of how to reconcile desire with whatever idea of virtue prevails in society can never be finally answered. The Scarlet Letter dramatizes this eternal human dilemma with great power.

Jane Ciabattari: Which elements of The Scarlet Letter seem to have changed the least as you teach the novel to the current generation?

Andrew Delbanco: Henry James credited Hawthorne with being the first American writer to explore the “deeper psychology.” And while the style and setting of The Scarlet Letter may feel antiquated, its psychological themes still strike many of my students as fresh and pertinent to their own lives. A young man (the minister, Dimmesdale) must decide between protecting his public reputation and exposing the secrets of his private life. A young woman (Hester) struggles between acceding to what is expected of her and what she craves. Even Hester’s bloodless husband (the well-named Chillingworth) is a portrait of someone we all have known or known about: a man whose life is overcome by jealousy and rage. The rules of the game—of courtship, public comportment, intimacy—may have changed since Hawthorne’s time, but he gets at facts of life that haven’t changed: love unrequited, the crushing responsibilities of parenthood, the fact that the pursuit of happiness is a struggle against long odds.

Moby-Dick by Herman Melville

Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick—on just about everyone’s list of great American novels—is the story of the “monomaniac” Captain Ahab, who inspires his crew of “renegades and castaways” to pursue a monstrous white whale by which he was mutilated on an earlier voyage until “his torn body and gashed soul bled into one another; and so interfusing, made him mad.” With an amazing range of verbal music—tragic, comic, lyric, epic—Melville conveys how hatred and vengeance can become the consuming motives of life. With love that overmatches Ahab’s hate, he weeps and laughs at and pities the human craving to find meaning in our brief existence and to resist the implacable power of fate. Both terrifying and moving, Moby-Dick is alternately a work of gigantic sweep and tender intimacy.

JC: What scenes and characters in Moby-Dick resonate most with students today?

AD: For many years, especially during the Obama era, my students were attracted to Melville’s celebration of America as a multi-racial society of limitless possibility radiating from “the center and circumference of all democracy.” They loved the friendship, with its erotic overtones, between the restless young white man, Ishmael, and the princely Polynesian, Queequeg, who protects him and seems to show the way toward a future free from all “social acerbities.” But since the rise of Trump, the center of the book has shifted back to Ahab—a cunning leader who nurses his own sense of injury and instills his followers with the same rabid fury that drives him to seek revenge. I only hope that someday Melville’s joyous sense of freedom will once again seem the most resonant and contemporary feature of his great book.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

When President Lincoln met Harriet Beecher Stowe at a White House reception, he is said to have remarked (no one knows if it’s true), “Is this the little lady who made this great war”? Stowe had written Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the hope of melting the hearts of northern and southern whites before the horror and brutality of slavery. How many minds she changed can never be known, but we do know that her book enraged slave owners in the South and unleashed a wave of antislavery sentiment in the North. To modern readers, the black characters of Uncle Tom’s Cabin are offensive stereotypes—stoic, simple, fawning, sly, enraged—but for that very reason Stowe’s book is a vehicle by which to travel into the years before the Civil War, when white America was just waking up to the humanity of an exploited and subjugated people.

JC: Uncle Tom’s Cabin, with its evocative images of the horrors of slavery, became the best-selling book of the nineteenth century, after the Bible, and shaped U.S. history. As you point out in your new book, Frederick Douglass “rejoiced that Stowe had ‘baptized with holy fire myriads who before cared nothing for the bleeding slave.” Do you think the stereotypes as perceived today keep the book from being valued by your students? Are there still lessons to be learned?

AD: The stereotypes are offensive. Yet they are useful for provoking discussion of the presuppositions all people carry in their heads about people unlike themselves. Stowe carries us back through the history of white attitudes in America toward black people—a history urgently relevant to the present time. As for lessons learned, students learn that opposing slavery did not necessarily mean acknowledging the full humanity of black people. Some northern whites opposed the expansion of slavery less out of moral outrage than because they didn’t want blacks in their neighborhood. For her portrait of the moralistic New Englander Miss Ophelia, a “bond-slave of the ought” who can’t stand the presence of black people even as she decries their enslavement in the South, Stowe may even have had in mind an element of “negrophobia” in herself. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, sentimental and shallow as it can sometimes be, is a tough-minded book. Again and again, it shows how even conscience-stricken slave owners sold their slaves to the highest bidder in order to stave off economic ruin for themselves. It makes us wonder whether appealing to people’s hearts is an effective way to effect social change, or whether the underlying economic forces are too powerful to be overcome by anything except a stronger countervailing force. Ten years after the book was published, America discovered the way to destroy slavery: by waging merciless war against the Confederacy that tried to preserve it.

The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton

Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth also takes us back to a lost world—in this case the hothouse scene of New York high society at the turn of the twentieth century—where we follow the downward spiral of a once-radiant debutante, Lily Bart, whose family is descending into bankruptcy and shame. Lily’s name suggests both the delicacy of a short-lived flower and the brute fact that she must barter her beauty for some wealthy man’s patronage before it is too late. Hers is an ineffably sad story as she struggles to retain some dignity and sense of personal worth while losing the marriage competition to rivals who have more money and social status with which to trade. The world of old New York feels almost as alien as the Puritan world of Hester Prynne, but the plight of a woman forced to choose between what she wants and what she needs feels current and urgent nevertheless.

JC: Wharton’s description of that downward trajectory is also dependent upon Lily’s fading beauty, her losing “the qualities distinguishing her,” which “were chiefly external, as though a fine glaze of beauty and fastidiousness had been applied to vulgar clay.” Do you think the fear of being single after the age of thirty that was so prominent in Wharton’s day still makes sense?

AD: Since Wharton’s day, the two options for middle-class women—marriage or “spinsterhood”—have given way to many more socially acceptable ways to lead one’s life. For most of my students, the very idea of a woman’s dependency on a man is repellent. In that sense, Wharton’s novel is a sort of anthropological study of a tribe (upper-crust New Yorkers) that’s now all but extinct. But we’re kidding ourselves if we imagine that young women don’t still have a “shelf life” within which they must prove themselves desirable in both a personal and professional sense. They know they face a brutal competition in which some will be winners and others losers. The House of Mirth is a frightening book, and I’m afraid that many of my students—not only women—experience the fear with a sense of intimate familiarity. They feel the clock ticking in their own lives as much as Lily Bart feels it in hers.

Native Son by Richard Wright

Reading Native Son is a brutal experience. The raw prose has a driving, pounding immediacy as Richard Wright narrates the desperate flight of a poor young black man in Chicago who kills the daughter of an affluent white family in a moment of bewildered sexual excitement, and is hunted by police to his doom. Bigger Thomas is not so much a fully drawn character as a projection of the patronizing white imagination—an animal in human form who has been taught to feel shame at his own color and the sordid life of furtive crime through which he feels flashes of pride. The writing has such visceral force that reading Native Son is both exhausting and exhilarating in something like the way Bigger feels simultaneously degraded and exalted by achieving infamy in the minds of people who had hitherto cared not a damn about his fate.

JC: There’s a chilling scene when Bigger, in his jail cell, says “I didn’t know I was really alive in this world until I felt things hard enough to kill for ’em…”

James Baldwin criticized Native Son as a “protest novel” in which “a necessary dimension has been cut away; this dimension being the relationship that Negroes bear to one another, the depth of involvement and unspoken recognition of shared experience which creates a way of life. What the novel reflects—and at no point interprets—is the isolation of the Negro within his own group and the resulting fury of impatient scorn. It is this which creates its climate of anarchy and unmotivated and un-apprehended disaster; and it is this climate, common to most Negro protest novels, which has led us all to believe that in Negro life there exists no tradition, no field of manners, no possibility of ritual or intercourse, such as may, for example, sustain the Jew even after he has left his father’s house. But the fact is not that the Negro has no tradition but that there has as yet arrived no sensibility sufficiently profound and tough to make this tradition articulate.”

David Bradley, who wrote the introduction to a new edition of the novel in 1986, has written, “It reminds us of a time in this land of freedom when a man could have this bleak and frightening vision of his people, and when we had so little contact with one another that that vision could be accepted as fact.”

Ta-Nehisi Coates has called Wright “didactic, cranky and insecure”: “I never believed Bigger to be an actual person. In fact, I thought Wright actually ended up doing the work of the racists he sought to denounce, by committing the common lefty mistake of portraying a people under siege as devoid of humanity. (Lefties say it’s because of systemic forces. Righties say it’s culture or genes. I don’t buy either.) The lesson Native Son for me was pretty simple—when you don’t write well the racists win.”

How do you account for the range of reactions to Native Son over the years?

AD: All these are strong critiques from powerful critics, but I don’t agree that Wright did not “write well.” I take the point that Native Son is susceptible to be read as if Bigger were somehow an adequate representation of “the black experience” (if one can ever speak in the singular of such a complex and variegated thing) and that his inarticulate, frantic, almost bestial fury is in some respects a demeaning caricature that plays well for racists and patronizing liberals. All that is true. But in depicting Bigger’s mute subservience as he is used, manipulated, and ultimately destroyed by whites who either enjoy or pretend not to enjoy their status as his masters, Wright wrote unblinkingly about a terrible truth at the core of American life. In a certain way, yes, Wright was a crude novelist—in the same way as were predecessors like Theodore Dreiser and Frank Norris—more focused on irresistible external forces than on the resilient inner life to which, say, Ralph Ellison turned in his modernist masterpiece, Invisible Man. But I don’t see how anyone can read Native Son without a shudder of recognition at its documentation of how America has dehumanized and vilified black men.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·