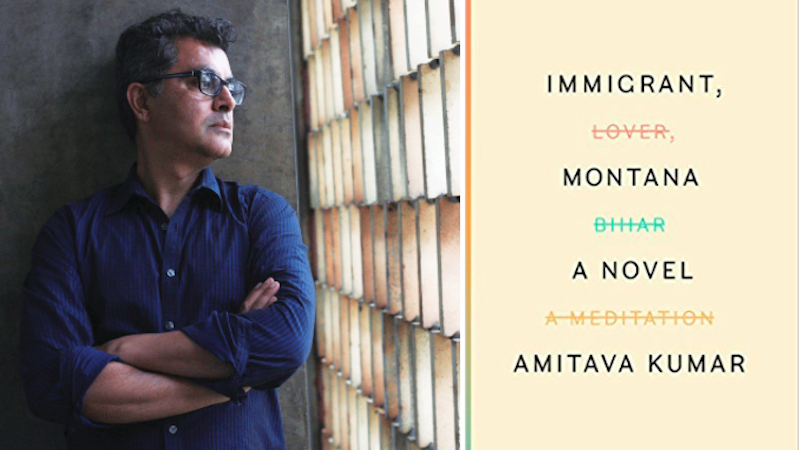

Amitava Kumar’s second novel, Immigrant, Montana, is published this month. He shared his list of five books about finding love (first love, new love) with Jane Ciabattari.

*

Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage, Alice Munro

(First of all, such a great title!) Good collection but there is nothing like the closing story, “The Bear Came Over the Mountain,” which I regard as one of the best stories of all time.

Jane Ciabattari: Indeed, that story, which toggles between a former professor’s ongoing care for Fiona, his wife of nearly fifty years, who has Alzheimer’s and becomes attached to a fellow resident of Meadowlake, and his memories of straying in the past. There are so many heart-breaking moments. Is there a point that strikes you as the most powerful? Most revealing? How does Munro manage this?

Amitava Kumar: The odd and brilliant thing is that Fiona is losing her memory—she is doing this as the paragraphs progress—but the story itself is recovering everything we don’t know about Fiona’s and especially Grant’s past. His infidelities. Each time I’ve read the story I’m satisfied with just this bit of genius, this ironical juxtaposition. And what I’m unprepared for are the turns in the tale. They don’t appear as mere plot twists to me. Each turn is surprising and yet so natural that we think that the pattern of the human heart is finally being revealed to us. How does Munro do it? I want to say that she knows more about love and grace than other writers but I also suspect there is a technical answer. By technical I simply mean that what she possesses is a deep artist’s difficult ambition, and that she was never going to be easily satisfied with simply one damning irony or sharp juxtaposition.

“The Lady With the Dog,” Anton Chekhov

I think I’m cheating again by focusing on a short-story rather than a book, but here is the reason why: such is the quality of story-telling, so acute its hold over the ebb and flow of emotion, that the story, like Munro’s “The Bear Came Over the Mountain,” feels epic.

JC: At first the story seems to be about a vacation tryst, two meeting in Yalta, the sea views, the walks, the natural beauty. And then they continue. There’s a moment that seems to me the center of the story, does it strike you that way?

“He had two lives: one, open, seen and known by all who cared to know, full of relative truth and of relative falsehood, exactly like the lives of his friends and acquaintances; and another life running its course in secret. And through some strange, perhaps accidental, conjunction of circumstances, everything that was essential, of interest and of value to him, everything in which he was sincere and did not deceive himself, everything that made the kernel of his life, was hidden from other people; and all that was false in him, the sheath in which he hid himself to conceal the truth—such, for instance, as his work in the bank, his discussions at the club, his presence with his wife at anniversary festivities—all that was open.”

Chekhov makes their story so much more nuanced and complicated than it is at first glance.

AK: That’s a good example that you have quoted. Chekhov sees everything so clearly, and describes it so cleanly, you would think nothing could outlast such a pitiless vision. But it does. Love lasts. Here’s an example of what is contained within one single sentence: “She sat down in the third row, and when Gurov looked at her his heart contracted, and he understood clearly that for him there was in the whole world no creature so near, so precious, and so important to him; she, this little woman, in no way remarkable, lost in a provincial crowd, with a vulgar lorgnette in her hand, filled his whole life now, was his sorrow and his joy, the one sorrow that he now desired for himself, and to the sounds of the inferior orchestra, of the wretched provincial violins, he thought how lovely she was.” If you think of the whole story as a long sentence, it contains so much that makes you at first dislike Gurov and yet, by the time the story ends, one cannot but extend to him, if not love, some tenderness and even pity.

The Lover, Marguerite Duras

I just taught this book last semester and my students hated it. They’ve been fired up by the #MeToo movement, and more strength to them, but all they would see in the book was abuse. They are right to see abuse but what I hear more insistently is a woman giving voice to her experience, her messy dealing with desire.

JC: Duras writes of a time hard to recall now, as her narrator, a young teen living in poverty in colonial Indochina, makes her first steps into owning her own power, and begins an affair with a businessman whose wealth might bring opportunity. Duras’ perspective is remarkable, as she gives us the first meeting on the ferry crossing the Mekong: “There’s the difference of race, he’s not white, he has to get the better of it, that’s why he’s trembling.” The Lover is autobiographical; Duras’ mother sold her to a businessman when she was 14. How has she transformed that experience?

AK: The Lover was published when Duras was 70. I believe she said something to the effect that it was completely autobiographical, and this assertion was, at least to some extent, responsible for the book’s wild popularity. One imagines that real life was not only plainer, it was also more brutal. If she had written the book as a young woman, how much more steeped in despair the writing would have been! But at the age at which Duras wrote The Lover, she could impose the distance not only of time but of fame and artistic achievement. What I hear more clearly in the prose, and it is so headlong, so beautiful, is a powerful voice giving shape to painful experience. We can see the vulnerable girl in the past and we are in touch with her suffering but we are also never not aware that here’s an artist in the present in full control of her art. If you were to accept the evidence only of the book, you might even think that there was genuine passion, true love, in both the girl and the man.

Light Years, James Salter

Everyone talks about Salter’s sentences, and they are right to do so. An extraordinary light seeps out from under his prose. I loved the book for its portrayal of a loving marriage, and I was shattered at the relationship’s demise, suffering through my identification with the male partner.

“No, really. Nedra, you know, I always… I’m here.”

“Viri, I’m fine.”

“Are you happy” he asked.

She laughed. Happiness. She meant to be free.

JC: I love Light Years, too. The opening pages are exquisite. But I have to say, what also stays with me is a slight confusion about why the relationship ended, and if it had to do with the times, when marriages were falling apart all over the country? And was it worth it? What do you think?

AK: I don’t know. I say this because I suffer from that same confusion. I didn’t know exactly why love had ended and taken root elsewhere. Or not. And was it worth it? I don’t know, I don’t know. I think of Light Years as a tremendous love story because it shows you love and then you discover that one of them is in love with someone else and their love is beautiful too. (Their love, and, where Salter is concerned, their love-making.) And even though, like me, you might be startled or confused when you discover this change, it is impossible not to say to yourself that this is right, this is what life is like.

White Teeth, Zadie Smith

There’s much to say about the love between different characters in this novel but what I want to say first is that one of the two epigraphs in my novel Immigrant, Montana, comes from White Teeth: “Oh, he loves her: just as the English loved India and Africa and Ireland; it is the love that is the problem, people treat their lovers badly.”

JC: That epigraph reminds me of another line in White Teeth, which is full of first- and second-generation Londoners, but focused on the Joneses and the Iqbals of Willesden. Smith refers to “Children with first and last names on a direct collision course.” In what other ways did White Teeth inspired Immigrant, Montana?

AK: “This has been a century of strangers, brown, yellow, and white.” That sentence appears at the start of the totally glorious passage from which you have taken that line. You know, such lines could have come from any of the range of writers of color that I see as sitting in a row at the counter in a bar. These writers are the chroniclers of postcolonial experiences. They are inevitably describing cultural mixing. And they are also providing models for how to write about people and about nations in the same sentence. In writing about children in a London park with names like Isaac Leung and Danny Rahman and Irie Jones, Zadie Smith shows that love between the parents was the result of a different kind of conquest between nations in the history of colonialism.