Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

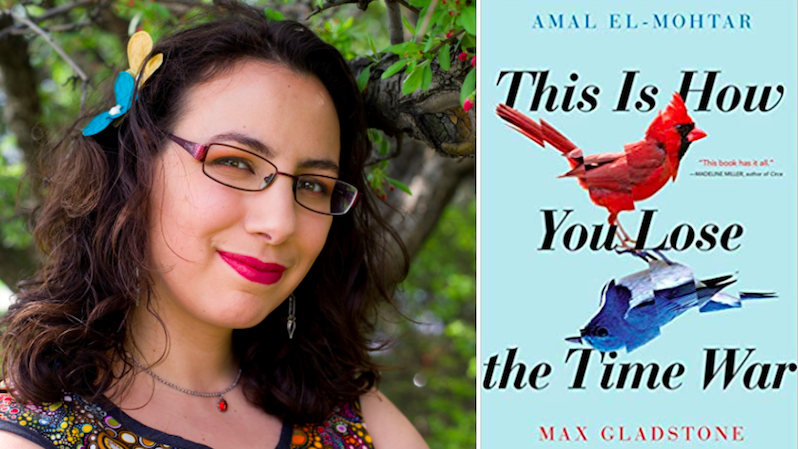

This week we spoke to Ottawa-based critic and writer, Amal El-Mohtar.

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

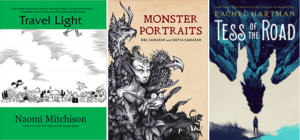

AEM: There are so many hard-done-by books, historically, that I utterly love: James Hogg’s The Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, John Keats’ Endymion. But of course the only reason I know them is that they’ve gone on to be recovered from history and now have a lot of scholarship devoted to them (more Keats than Hogg, obviously, but that’s surely only a matter of time). So I’m going to go with Naomi Mitchison’s Travel Light, which I actually have reviewed—but to have reviewed it in 1952, to have favourably compared its slim unprepossessing elegance to The Hobbit and placed it in permanent conversation with Tolkien’s books (which she reviewed!) would have been utterly wonderful.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

AEM: I’m cheating and doing two: Monster Portraits by Sofia and Del Samatar (which I reviewed for the NYTBR), and Tess of the Road by Rachel Hartman (which I reviewed for NPR). I’m further cheating, I guess, because I certainly have heralded these books all of the past year, and Tess of the Road was nominated for the Andre Norton Award (but didn’t win!), so I’m just here to reiterate that these extremely different books are magnificent and I love them fiercely.

I’m sorry, I cheat at books. (Never at cards, though!)

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

AEM: I often encounter positions and opinions with which I disagree, but I’m hard put to rank them against each other for the title of Greatest. I suppose one thing that often irritates me is the notion that critics need to be scathing to be interesting or entertaining—that to criticize a book is to perform some kind of self-aggrandizing dance of destruction. I have definitely read righteous take-downs of bad books and enjoyed them, but the thing I strive do most as a critic is open up a space in which to have a conversation about the book; to not render some kind of singular, authoritative value judgement so much as identify the areas I find most generative for discussion, for thinking about. Inevitably I find that doing so actually gives readers more information about whether or not they’d enjoy a book themselves than any summary sentence I pronounce on its Goodness or Badness.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

AEM: You know, I’m not totally sure I encountered a great deal of book criticism before the age of social media! I’m aware of having read film and television reviews, but not book reviews—I was too voracious a devourer of books to be guided in my choice of them except by word of mouth.

I think a big change, though, is how social media has simultaneously increased the accessibility of authors and the visibility of reader responses, causing two spheres of enormous vulnerability and intimacy to abut with some really awful (and, admittedly, sometimes wonderful) results. There are whole essays to be written about how Amazon’s purchase of Goodreads has affected discourse and criticism, which I won’t attempt here, but it’s on my mind a lot. Whether I’m reading for myself or for review, I want to be able to talk about my experience of the book away from the author’s gaze; we live in a world where the author, far from being dead, has achieved a kind of reluctant omniscience. As a writer of fiction I’d quite like not to be tagged into negative reviews of my work, so I never ever tag authors when linking to my own reviews, even if they’re mostly positive—I want there to be distance between us, to avoid any kind of dynamic where they have to thank me for putting a mixed review on a huge platform. But social media makes this almost impossible! Whenever I post a review without tagging the author, some enterprising soul always, always takes it upon themselves to do it on my behalf, forcing us into Twitter proximity, no matter how many times I ask for this behaviour to be cast into the sea. Authors finding the reviews themselves is totally fine, and expected; authors being forced through awkward social media dynamics to respond to me directly? That’s anathema.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

AEM: So, the first three critics who came to mind are not usually book critics, but I’m naming them anyway because I think the craft of criticism, of speaking publicly and thoughtfully and generously, cuts across a lot of individual interests. (Also, I read them a lot more than book critics, just because the time demands mean focusing so much on consuming fiction without being influenced by others’ views in order to figure out my own in a vacuum.) Emily Nussbaum’s writing about television and humour, and Meghan McCarron or Helen Rosner writing about food and restaurants, are absolutely immediate must-reads for me. I feel like I’m learning from and striving towards their craft all the time. But besides them, Carmen Maria Machado writes non-fiction that’s absolutely as gorgeous and devastating as her fiction—I think about this essay of hers in The Atlantic in particular. I can’t wait for her forthcoming memoir! I realize that I may be blurring the line between criticism and essays, but maybe that’s a feature instead of a bug. I re-read Sofia Samatar’s essays—”Skin Feeling,” “Why You Left Social Media: A Guesswork,” “On the Thirteen Words that Made Me a Writer”—more than anyone else’s.

*

Amal El-Mohtar is the New York Times Book Review‘s science fiction and fantasy columnist, and lives in Ottawa with her spouse and two cats. Her short fiction has won the Hugo, Nebula, and Locus awards, and her poetry has won the Rhysling award three times. Her work has appeared in numerous anthologies including The Starlit Wood: New Fairy Tales, The Djinn Falls in Love & Other Stories, and The New Voices of Fantasy; in magazines such as Tor.com, Lightspeed, Strange Horizons, and Fireside; and in her own collection of poems and very short stories, The Honey Month. A novella co-written with Max Gladstone and titled This Is How You Lose the Time War is forthcoming from Saga Press in July. Find her online at amalelmohtar.com or on Twitter @tithenai

*

· Previous entries in this series ·