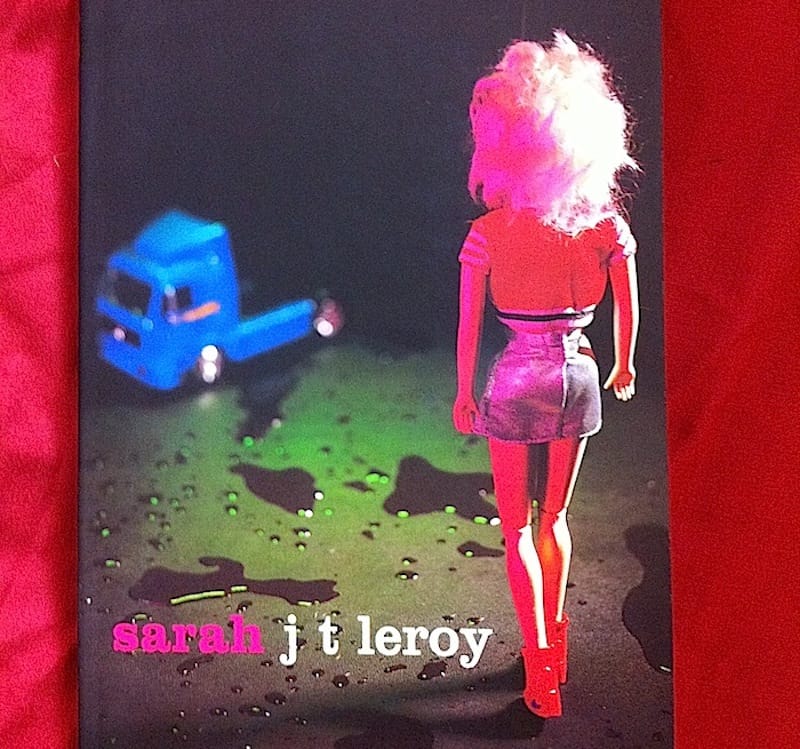

“Every so often a book bursts on the scene and triggers irresistible questions: Who is the author? What made him a writer? Is the book autobiographical? Is it fantasy? This is the case with Sarah, J. T. LeRoy’s deft and imaginative first novel. Does it matter that he is 20 years old? That he grew up in rural West Virginia and later on the streets of San Francisco? That he started publishing at 16, under the pseudonym Terminator? It does. And yet it shouldn’t.

Sarah is a coming-of-age novel that reads like a perverse children’s tale — an Alice in Wonderland on acid — with the ironic twist that its hero longs to become a woman, not a man. It’s the tragicomic story of a 12-year-old boy — Snow White taken up by the Seven Dwarfs, except the Seven Dwarfs happen to be a bunch of truck-stop transvestites, working the lot behind the Doves Diner in West Virginia’s back country. Some of the whores, or ‘lot lizards,’ are female; one of them is the boy’s mother. She’s young, beautiful, blond and very, very messed up … starved for his mother’s attention, the boy, who is nicknamed Cherry Vanilla, aspires to supplant his mom and become the best lot lizard in the state. The Doves Diner is a fantastical place, as much a product of hard-core realism as comic fantasy.

…

“But the relatively safe world of the Doves Diner becomes too confining for the boy, who has adopted his mother’s name, Sarah. He sets out on a dangerous journey to find himself — or is it herself? First stop: a pilgrimage to ‘the patron saint of lot lizards,’ a stuffed animal known as Holy Jack’s Jackalope. This turns into a hilarious scene where transvestites line up ‘in their evening finest’ to be blessed by the jackalope, whose antlers seem miraculously to grow.

When Sarah meets an evil pimp named Le Loup, there’s no turning back. Le Loup’s kingdom is a venomous truck stop where yellow flowers bloom out of the skunk cabbages ‘like rows of hepatitis eyeballs’ and where 18-wheelers are precariously balanced on ‘disjointed tar slabs’ that surround his diner ‘like petals on a daisy.’

For a first novelist, J. T. LeRoy is astonishingly confident. His language turns the tawdriness of hustling into a world of lyrical and grotesque beauty, without losing any of its authenticity. One can clearly hear an Appalachian twang in his prose and, along with his gallows humor, the baroque religiosity of the South. In spite of Sarah’s lack of sexual innocence, his language is always fresh, his soul never corrupt. His sweet and pure vision makes even the nastiest scenes bearable.

The novel’s ending is a bit too neatly wrapped up. Having survived his trials, Sarah still hopes to be reunited with his mom. It doesn’t happen, and that brutal return to reality will make the boy grow up. It is a fitting ending, but as the magic wears off, the writing loses some of its emotional power, its fairy dust. One almost wishes that Sarah, like Peter Pan, would remain a child, or, at least, keep his childlike vision. But what choice does he have but to become a man?”

–Catherine Texier, The New York Times, May 7, 2000

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.