Sooner or later…one has to take sides. If one is to remain human

*

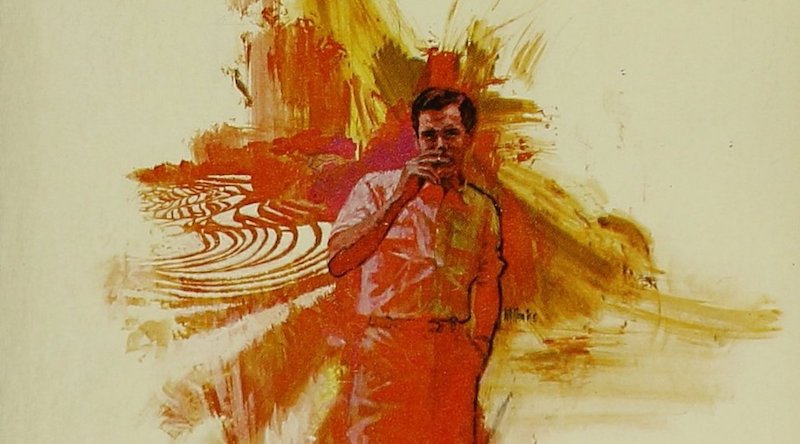

“Graham Greene’s new book is quite different from anything he has written before. It is a political novel — or parable — about the war in Indochina, employing its characters less as individuals than as representatives of their nations or political factions. Easily, with long-practiced and even astonishing skill, speaking with the voice of a British reporter who is forced, despite himself, toward political action and commitment, Greene tells a complex but compelling story of intrigue and counter-intrigue, bombing and murder. Into it is mixed the rivalry of two white men for a Vietnamese girl. These elements are all subordinate to the political thesis which they dramatize and which is stated baldly and explicitly throughout the book.

As the title suggests, America is the principal concern. The thesis is quite simply that America is a crassly materialistic and ‘innocent’ nation with no understanding of other peoples. When her representatives intervene in other countries’ affairs it causes only suffering. America should leave Asians to work out their own destinies, even when this means the victory of communism.

In Greene’s previous novels, geographic and social backgrounds have been used with great skill to make the foreground action more dramatic, but social or national issues have never been argued for their own sake. In The Quiet American the effect of circumstances is specifically ideological and political. Everything that the British reporter, Fowler, sees of the war, of the indiscriminate slaughter of civilians, drives him out of his ‘uninvolvedness’ toward a decision. Above all, he is moved by his hatred of the Americans.

“If much of the description of Indochina at war is written with Greene’s great technical skill and imagination, his caricatures of American types are often as crude and trite as those of Jean Paul Sartre. He is not ashamed as an artist to content himself with the picture of America made so familiar by French neutralism; the picture of a civilization composed exclusively of chewing gum, napalm bombs, deodorants, Congressional witch-hunts, celery wrapped in cellophane, and a naive belief in one’s own superior virtue.

Even in this indictment the book is inconsistent. As a non-implicated man who really understands the East, Fowler scorns American liberals for trying to introduce into Asia their textbook notions of democracy and freedom. ‘I have been in India,’ Fowler says, ‘and I know the harm liberals do.’ At the same time, sounding very much a liberal, he accuses the Americans of selfish opportunism, of letting the French do the dying while they clean up commercially. Emotionally and usually Fowler describes the war as a meaningless slaughter of women and children, as if no enemy existed, and yet he is in touch with this enemy, the Communist Vietminh, and expects it, because of its superior understanding and organization, to win the war.

“What will annoy Americans most in this book is the easy way Fowler is permitted to triumph in his debates with the Americans … Pyle, the American, does not remind Fowler of the thousands of individuals who make desperate escapes from Communist countries every week in order to life as humans. He only replies uneasily, ‘You don’t mean half what you are saying.’ There is no real debate in the book, because no experienced and intelligent anti-Communist is represented there. Greene must feel either that such men do not exist or that they do not serve his present purposes.

It would be wrong, of course, to wish to argue, if these custom-made characters were merely characters and merely speaking for themselves. Fowler, however, is often quoting almost verbatim from articles which Graham Greene wrote about Indochina for The London Times last spring. He had visited the Communist territories and been much impressed by the Communist leader Ho Chi Minh.

When The Quiet American is read against the background of these articles, it can be seen to be more profoundly related to Greene’s earlier religious novels than its polemic character at first suggested. In those novels God is reached only through anguish because religion is always paradoxical in its demands. Rationalists are forced to accept the crassest of miracles. In believers, love and pity often war with the chance of salvation. God is most God when His earthly Kingdom is weakest, and His mercy sometimes looks like punishment.

When Graham Greene grants primary justice to the Communist cause in Asia, and finds insupportable its resistance under the leadership of America, he raises inevitably this question: Has he reconciled himself to the thesis that history or God now demands of the church and of Western civilization a more terrible surrender than any required of the tormented characters in his fiction?”

–Robert Gorham Davis, The New York Times, March 11, 1956

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.