I lived in a world that at any moment could erupt into fire.

It was the sort of knowledge that kept you on your toes.

*

“Memoirs are our modern fairy tales, the harrowing fables of the Brothers Grimm reimagined from the perspective of the plucky child who has, against all odds, evaded the fate of being chopped up, cooked and served to the family for dinner. What the memoir writer knows is what readers of Grimm intuit: the loving parent and the evil stepparent may in reality be the same person viewed at successive moments and in different lights. And so the autobiographer is faced with the daunting challenge of describing the narrow escape from being baked into gingerbread while at the same time attempting to understand, forgive and even love the witch.

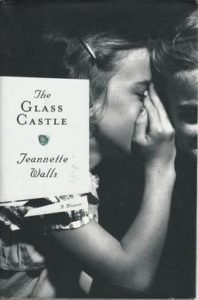

How fitting, then, that the title of Jeannette Walls’ chilling memoir, The Glass Castle, should evoke the architecture of fantasy and magic. The transparent palace that Walls’s father often promised to build for his children functions as a metaphor for another fanciful construct, the carefree facade with which two people who were (to say the least) unsuited to raise children camouflaged their struggle to survive in a world for which they were likewise ill equipped.

Rex Walls was a gifted, seductive and deeply damaged man whose ‘little bit of a drinking situation’ made it impossible for him to hold the jobs (as a mining engineer and an electrician) he procured through a dazzling mix of prevarication and charismatic charm. Rose Mary Walls, a painter, writer, free spirit and self-styled ‘excitement addict,’ entertained certain convictions about life in general and parenthood in particular that, all too predictably, helped pave the road to grief and disaster.

“Reared by a mother who believed that kids should be left alone to reap the educational and immunological benefits of suffering, Jeannette Walls, her brother and two sisters rapidly discovered that their peripatetic, hardscrabble life — constantly moving from one bleak, dusty Southwestern mining town to another — had no end of painful lessons to teach them. At 3, Walls was so severely burned while boiling hot dogs that she required skin grafts and spent six weeks in the hospital, from which her father ‘rescued’ her, ignoring the alarmed cries of a nurse. The experience left Jeannette with physical scars and a worrisome case of pediatric pyromania.

The memoir offers a catalog of nightmares that the Walls children were encouraged to see as comic or thrilling episodes in the family romance. Pursued by bill collectors (or, as Rex claimed, conspiratorial F.B.I. agents), the family made a getaway so hasty that Dad felt compelled to toss Jeannette’s recalcitrant cat out the car window. Bitten by a scorpion, 4-year-old Lori suffered convulsions. Accidentally hurtled from the family station wagon onto a railroad embankment, Jeannette had to wait in the desert sun until her parents realized she was missing; while she scraped off the blood, her father plucked pebbles out of her face with pliers.

Jeannette was molested by a neighborhood pervert. Later, when her parents resolved to throw themselves on the slim mercies of Rex’s family, they moved to West Virginia — to a vile hamlet along a river distinguished by having, her father proclaimed, ‘the highest level of fecal bacteria of any river in North America’ — where Jeannette was groped by an uncle. A visit to the zoo ended when Rex and his daughter reached inside the cheetah’s cage to pet the giant cat, while a family holiday erupted in flames as prankish Dad set the Christmas tree ablaze with his cigarette lighter.

“Along the way, the children enjoyed a characteristically idiosyncratic version of home schooling. Their mother taught them reading and the health advantages of drinking unpurified ditch water, while their father explained ‘how we should never eat the liver of a polar bear because all the vitamin A in it could kill us. He showed us how to aim and fire his pistol, how to shoot Mom’s bow and arrows, and how to throw a knife by the blade so that it landed in the middle of a target with a satisfying thwock.’ Walls recalls that ‘by the time I was 4, I was pretty good with Dad’s pistol, a big black six-shot revolver, and could hit five out of six beer bottles at 30 paces. . . . It was fun. Dad said my sharpshooting would come in handy if the feds ever surrounded us.’ Surely it suggests something about our educational system that whenever the Walls children did attend school they turned out to be academically ahead of the local kids, who tormented them for their outsider oddness.

Walls has a telling memory for detail and an appealing, unadorned style. And there’s something admirable about her refusal to indulge in amateur psychoanalysis, to descend to the jargon of dysfunction or theorize (beyond certain tantalizing clues that occurred to her during their stay with her West Virginia grandmother) about the sources of her parents’ behavior. But what’s best is the deceptive ease with which she makes us see just how she and her siblings were convinced that their turbulent life was a glorious adventure. In one especially lovely scene, Rex takes his daughter to look at the starry desert sky and persuades her that the bright planet Venus is his Christmas gift to her. Even as she describes how their circumstances degenerated, how her mother sank into depression and how hunger and cold — and Rex’s increasing irresponsibility, dishonesty and abusiveness — made it harder to pretend, Walls is notably evenhanded and unjudging.

“Readers will marvel at the intelligence and resilience of the Walls kids. We root for them when they escape, one by one, to New York City, where Jeannette attended college, married and found work as a magazine columnist. And we begin to fear for them all over again when their parents follow them to Manhattan, where Rex and Rose Mary exhaust their children’s patience and hospitality and wind up homeless, eventually living as squatters in an abandoned building on the Lower East Side.

At times, the litany of gothic misfortune recalls Harry Crews’s classic memoir, A Childhood. The two books have striking similarities; both, for example, feature the horrific scalding of a child. But to think about Crews’s book is to become aware of those mysterious but instantly recognizable qualities — the sensibility, the tonal range, the lyrical intensity and imaginative vision — that distinguish the artist from the memoirist, qualities that suggest the events themselves aren’t quite so interesting as the voice in which they’re recounted.

The Glass Castle falls short of being art, but it’s a very good memoir. At one point, describing her early literary tastes, Walls mentions that ‘my favorite books all involved people dealing with hardships.’ And she has succeeded in doing what most writers set out to do — to write the kind of book they themselves most want to read.”

–Francine Prose, The New York Times, March 13, 2005

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.